Some say a meme dies when the New York Times writes about it, but that might be giving the Times too much credit. Their best boy Ezra Klein wrote/podcasted last month about NPCs:

A few years back, the online right became enamored of a new epithet for liberals: “NPC,” short for “nonplayer character.” The term was lifted from video games, where “NPC” refers to the computer-controlled characters that populate the game while you, the live player, make decisions. NPCs don’t have minds of their own. They’re automatons. They do as they’re told.

…liberals, in this story, thought what they were allowed to think, said what they were allowed to say. You might have seen the memes — featureless gray faces, sometimes surrounded by liberal icons. Elon Musk loved posting them.

The “featureless gray faces” Klein cites are Wojaks, specifically NPC Wojak, a robotized variant of basic Wojak that was first used in the fall of 2018. The “NPC” term had been floating around 4chan and other platforms for a long time. Wojak himself originated around 2010 on European image boards, and from there grew into a sprawling, dynamic memelore tradition that still exists to this day.

The earliest NPC Wojak meme Know Your Meme records, from Twitter, shows a group of the NPC Wojaks “assimilating” a normal Wojak.

There is a double valence to the Wojak meme tradition, which is why it interests me so much. On the one hand, Wojak, with his wistful expression, is a digital everyman, representing the put-upon typical user. He was a collective self-portrait, the face matched to the voice of any commenter. But on the other hand, Wojak is like a Barbie doll that you can bully: memers put him in different outfits, give him different expressions and make him represent anyone they want him to represent. So at the same time as Wojak was a self-portrait for anonymous posters, he was also turned into a caricature of their foes, transformed into “soyjak” by giving him an emasculating neckbeard and glasses.

The first function echoes the Pepe meme, and so does the second to a lesser degree (although there is no “soy” equivalent in Pepelore — there may be weaker or more cringe Pepes, but the meme is nearly always used to represent an in-group, not an out-group). Wojak was also never as famous as Pepe. And in recent years — post 2020 in particular — we’ve seen a mainstream and even leftist appropriation of Wojaklore.

However, like in any historical analysis, it is important not to fall into the mistake of presentism. The earliest NPC Wojak meme is from 2018 and participates in that tradition of modifying Wojak to depict a group you want to attack. At that point, Wojak was still a mostly niche and conservative phenomenon.

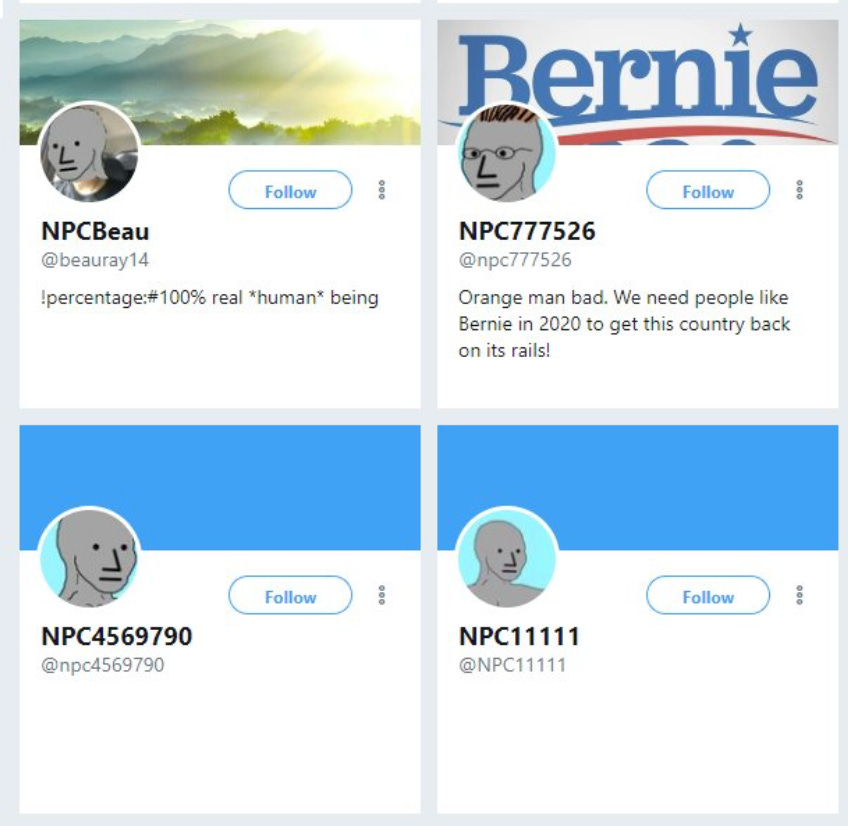

The fall of 2018 is right before the midterm elections in the United States and around the peak of the rightwing fury over supposedly getting censored by social media platforms. The meme’s rising popularity was paired with a liberal backlash, which called it fascist and dehumanizing. Rightwingers made Twitter profiles with NPC Wojak pictures, mocking online liberals by calling them the equivalent of a bot.

The flames of NPC Wojak were fanned by the same mainstream platforms it criticized. After Twitter cracked down on the 1,000+ NPC Wojak profile picture accounts, outlets like the New York Times covered it (Klein was not the first) and then other outlets like The Verge wrote about how the Times covering NPC Wojak was amplifying its rightwing message.

It’s important to note that no meme trend is truly owned by anyone, and it’s a bit inaccurate to say a meme, uniformly, has a “rightwing message.” There were lots of leftist or liberal versions of NPC Wojak created during that viral moment (albeit they were the minority and they didn’t get as much press). The meme was easy to turn around on MAGA people.

In the example above, programming syntax represents the instructions given by one NPC to another. The core of the meme’s message is that arguments by the other side don’t have to be refuted because they are fake. Seeing your opposition as essentially artificial makes it easier to imagine they steal elections, that the true and only “voice of the people” sounds like yours. Visually, the NPC Wojak meme also erases the individuality and diversity of the other side. They all look the same.

Alex Jones of Infowars, capitalizing on the frenzy, created an “NPC Meme Competition” with a $10,000 grand prize to be awarded to the winning meme. Here’s one of the submissions:

And another one, below:

The meme which ended up winning the Infowars competition was a video edit of the 1988 film They Live. The creator of that meme, called Carpe Donktum, would later be famously retweeted by Donald Trump for a different video edit and banned from Twitter (in part because of DMCA takedowns of his content, which was all about editing memes into clips from movies or advertisements).

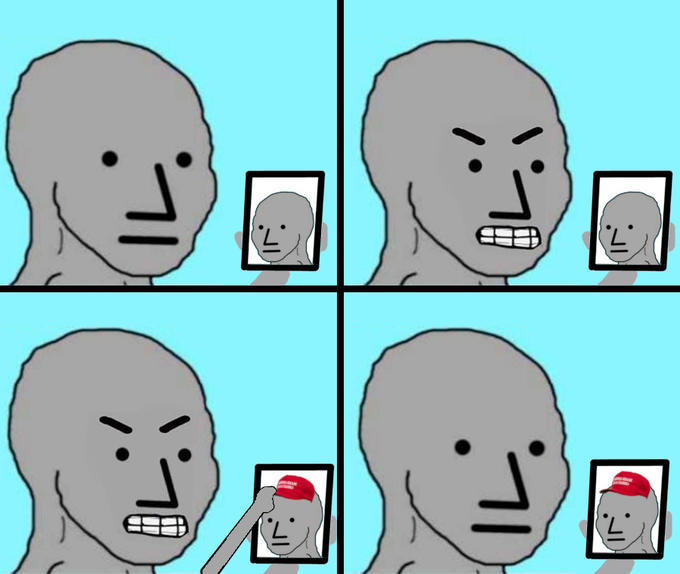

A couple of variants emerged to the NPC Wojak. One turned it into a four panel, sometimes incorporating an old Rage Comics character. One of my favorites of this trend (seen below) has the NPC Wojak fighting with itself.

Another variant featured an “update chip” getting installed in NPC Wojak’s brain. I have, according to my own taste, picked a “meta” example of this which makes fun of the way the meme was used. But such versions of NPC Wojak were and are far from rare: as soon as the meme was embraced by people who hated mainstream media, it was also embraced by those wanting to mock the haters.

NPC Wojak was famously used by Elon Musk in March 2022. Again, the NPC Wojak serves the function of collapsing a diversity of causes, each with their own complexities, into “the current thing” — and reducing the individuality of opponents into one NPC Wojak.

“High Agency”

I can’t help but read NPC Wojak in conversation with “high agency,” a trending term online which Business Insider described in a recent piece. You’ve doubtless seen posts about “high agency” if you have the misfortune (or, honestly, the masochistic habit) of spending time on X lately.

A “high agency” person is a risk taker who doesn’t take no for an answer. They are entrepreneurs, builders, coders, top athletes, and winners. High agency people cross boundaries, “move fast and break things,” disdain orthodoxies (nevermind that the discourse of “high agency” itself has become an orthodoxy). NPC Wojak is the opposite.

“High agency” might be thought of as just another variant of the entrepreneurial mindset grindset. Virtue, from this point of view, derives from hard work and autonomy. There is an intersection with self-help culture, and a kind of Randian veneration of individualism. The high agency person’s assertion of self over the physical body and social world is its own superpower. Egg-headed goon and chronically-online billionaire Marc Andreessen says “the dirty secret of hard drugs is that a small minority of super-disciplined high-agency people really can handle them.”

My other favorite Andreessen quote: “it’s a test of manhood as to whether you can have a blue screen in your face for three hours and then go right to sleep.” Implicitly, the “high agency” person is male. And staring at a blue screen. The morality of “high agency” is tied to a dismissal of the physical (the body’s limits) and of the social (other peoples’ bodies). It is a worldview which does away with reasons and ideas. Since the act of “building” is a virtue in itself, it doesn’t matter what you are building — it’s just important that you’re building for yourself. This is a comfortable fantasy, but it is solipsistic and escapist. It avoids substance and ambiguity — like the NPC Wojak meme, it skirts the substance of whatever issue is at hand and instead engages with who you are for thinking one way or another.

You might read the tech world’s love of “high agency” as a kind of reaction against its own excesses. The people who engineered a spawn of AI agents and the interfaces, platforms, and algorithms through which so much of life today is automated are insisting upon their autonomy from the system they helped build. Being high agency means being unbound by the things which you made, and which also made you.

There’s also a possible anxiety around agency — it’s both a virtue they can claim when others accuse them of being dumb or evil, and a status they can cling to even as they continually talk about AI agents becoming better than human agents or, as Peter Thiel wrote in a recent editorial, the world-historical force of “the internet” which “augurs the apokalypsis of the ancien regime.” Seeing yourself as a free agent while also seeing yourself as the living expression of a suprahistorical force is a bit of a paradox, no?

NPC Wojak represents that ancien regime which Thiel talks about — the establishment, the media, perhaps the overall bourgeois professional world. But in the meme, that ancien regime is pictured in terms of the digital world: both as a robot/computer, and as a Wojak meme. It has no authority because any source of meaning beyond self-assertion — whether it is law, empirical observation, interpretation and reinterpretation, another person — is not recognized as real.

One thing I keep turning back to is Sherry Turkle’s analyses of computer hobbyists in the 1980s and 1990s. I mentioned her in my post on the algorithmic gaze. Turkle says that for some, computers offer a balm for existential anxiety. It’s comforting to see our ambiguous world and selves as ultimately bounded and ruled by a discoverable set of logics, the way they are within a computer. Here’s a quote from one of her lectures:

…immersion in programmed worlds puts us in reassuring environments where the rules are clear. For example, when you play a video game, you often go through a series of frightening situations that you escape by mastering the rules -- you experience life as a reassuring dichotomy of scary and safe. Children grow up in a culture of video games, action films, fantasy epics, and computer programs that all rely on that familiar scenario of almost losing but then regaining total mastery: There is danger. It is mastered. A still-more-powerful monster appears. It is subdued. Scary. Safe.

Implicit in not just video games but social media is that “mastery” which the device appears to offer us. The entire purpose of the world as simulated by a digital interface is to frame and affirm your agency. I remember the pleasure, as a child, of organizing the app icons on the screen of my first iTouch — one of the first times I felt a sense of adultish autonomy. When TikTok serves the exact right video on my FYP, it reminds me of that feeling. A screen which continuously recognizes and affirms your agency — obeying commands, changing its shape to fit your whims — is a technology that makes you feel like your agency is the law of the universe, or at least the little universe in your pocket where you spend most of your time. The issue is when people forget the world is not a computer.

It is possible to have a computer experience that is more nourishing and realistic, which doesn’t circuit everything through the self before it reaches the world. And this does exist, as a counter-current within the exploitative and false internet we live in.

One part of that countercurrent is the process and tradition of meme-making. As I said in my post on phenomenology and memes, a meme is fundamentally an experience of attachment to others, joining your individually-generated component to something other people made. Memes dramatize and illustrate your belonging to a force beyond yourself. Within a computer experience that is circuited for solipsism, memes are a kind of rupture, and a reminder of who you may really be beyond your own reflection.

last three paragraphs are fire