"algorithmic gaze"

would Walter Benjamin like memes?

Cherished mutual Adam Aleksic made a great post about the idea of an “algorithmic gaze,” which is well worth reading — check it out at this link.

I poked a little bit towards what he’s talking about in my 40 minute Skibidi Toilet video essay on YouTube, specifically the second section where I discuss the show’s decision to render all action through the continuous POV of one of the CCTV camerahead soldiers. Since every episode of Skibidi Toilet is an uncut slice of time from literally inside the head of a cyborg, we are not just seeing through a camera, like we are in film and television, but as a camera. Gaze, in Skibidi Toilet, is an active question — as it is in most memes and online media.

What I want to do here in this overlong post is sketch the idea of an “algorithmic gaze” out a little further, in conversation with Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935) and my analysis of Skibidi Toilet (2023). There’s four parts: first, a description and analysis of the “cinematic gaze” drawing from Benjamin and others working downstream of him, second, a provisional theory of what the “algorithmic gaze” might be, third, a tentative description of one of the devices by which an algorithmic gaze gets expressed, and fourth, a set of open questions that I want to dig into further.

If this all interests you, read on! And you can also check out my recent conversation with cherished mutual Frederick Woodruff about Skibidi Toilet, the metaphysical side of memes, and divination online.

I. Cinematic Gaze

There’s a robust tradition in cultural and media theory addressing the ways film audiences identify with the image in front of them. It’s different than looking at a painting, because you’re not looking through human eyes, but through a camera — which alters your visual experience. Since visual experience comes before all else in a movie, the way I interpret, empathize with, and understand a film is downstream of how I see it.

With camera vision comes what you might call a variety of “suspension of disbelief.” We forget that, through a camera, we are seeing things that human vision really can’t see, like aerial drone shots, close-ups, and CGI shots. We often forget the camera is even there. We are also seeing conversations and events occur in ways that we ourselves don’t experience them: human visual experience doesn’t render the world as a series of rectangles, doesn’t cut other people off at the chest. We also don’t see out of sequence, flashing forward or backward through years, blinking and finding ourselves in another room or another city, as happens in movies.

Walter Benjamin in 1935 argued that film (and the process of “mechanical reproduction” more broadly) disconnects the image from its traditional mooring in space, time, and lived experience. It used to be that you could only see an event happen once, you had to go to a particular room in a particular museum to see a work of art. The grounding of art in a “you had to be there” gave it “aura.”

When you’re a 15th century peasant looking at a statue in church, you must be in your body, you must see it as what you literally are — a worshipper, a body engaged in this activity, which was previously in another place doing other things, and will soon be in the next place.

Marshall McLuhan defined media as “extensions of man,” and the camera (or the whole film apparatus of editing, etc.) might be seen as an extension of vision, bringing our eyes and brains to places our normal bodies cannot take them due to our fixity in time and space. Watching a film, you enjoy a visual experience that is only possible through machines that see in ways you can’t — that can stretch and slow time, switch and swivel through space, chop the seen world up into discrete pieces rather than a continuous whole. By extending human perception, the camera changes the dimensions of the world. In one banger passage, Benjamin writes:

… (the camera) manages to assure us of an immense and unexpected field of action. Our taverns and our metropolitan streets, our offices and furnished rooms, our railroad stations and our factories appeared to have us locked up hopelessly. Then came the film and burst this prison-world asunder by the dynamite of the tenth of a second.

Seeing through machines offered the ability to take things out of context, to re-embed the image into reality and give it a different relation to the viewer. It also offered a new way to see our place in the world. “The audience takes the position of the camera; its approach is that of testing,” says Benjamin. Rather than ritually revering an image for its aura because we exist in the same context as it, since we are trapped and created within its field of action, we step outside of that context with the help of a machine and “test” the image, since it comes to us rather than us coming to it.

Laura Mulvey’s “male gaze” concept, from 1973, follows this point but complicates it: the identification with a camera doesn’t just warp our vision because of its technical capacity to decontextualize time and space, but because it is embedded within a particular social form. When film cameras point at women, they usually align with or anticipate the way a male spectator might observe a woman. Crucially, this “male gaze” is not any singular man’s gaze but a kind of ambient, generalized point of view — like the “judge inside of your head” that people talk about.

When you think of the male gaze, you might think of a camera tracing some actress’ legs, but there’s also the cut to an actor’s face looking at her desiringly right after and serving as a kind of audience surrogate. There’s the fact that the actor’s legs are never filmed that way. There’s the social context around movie production and consumption.

And then, from the other direction — the “testing” posture of a film audience, when applied to a woman’s body on screen, chopped up and decontextualized by a camera, is then exported to real life. Already for the past hundred years, we have a spent a great number of our conscious hours seeing as cameras, and it’s undoubtedly changed the way we experience the visual world and one another.

The content of an image is never just what it is of, but who it invites us to be while seeing it.

II. Algorithmic Gaze

In his piece, Aleksic foregrounds the physical experience of watching TikTok, “that passive, amniotic closeness of being curled up under your covers with your phone glowing in front of your face, able to summon new videos with each swipe of your thumb.”

TikTok offers a “flow state,” where our attention is cunningly grabbed and maintained. But it’s also useful to consider who we are watching TikTok as.

the viewer of a TikTok is typically solitary. It’s an intimate setting, the screen is private and owned rather than public and shared like the film screens Benjamin was looking at in 1935.

the viewer is in complete control, the screen rarely disobeys, and is tailored to their wishes.

the time of the screen maps exactly onto time as experienced by the viewer: the movie will not end in an hour, the scroll is infinite. The only limit on how much time you could spend on TikTok, or what time you can go on, is your own schedule.

the space of the screen maps exactly onto space as experienced by the viewer: you don’t have to go anywhere to see TikTok, the phone follows you around to everywhere. Increasingly, with the environmental integration of computing (QR codes on menus, map apps) space as seen by the phone adheres exactly to space as experienced in life.

And there is a fifth point here, which is the result of the four above: we built this For You Page brick by brick. What you see on the scroll is an extension of you, continuous with space and time as you experience them, taking place in an intimate way you seem to control. What you see on the scroll is the result of targeted data harvesting and analysis of your preferences and self, funneled through a specific set of interfaces and technologies that feeds recursively into itself and into you.

This phenomenon has been a part of personal computing from the start. Sherry Turkle, the great anthropologist of the early internet, titled her 1984 book The Second Self after a remark a sixth-grader said to her during her field work on children learning to program: “when you program a computer, there is a little piece of your mind and now it’s a little piece of the computer’s mind.”

Putting a little piece of your mind into the computer’s mind and seeing it reflected back to you as a “second self” is a good feeling. “The rest of the world blurs away as we enter a tender, individualized connection with this unique part of ourselves,” Aleksic writes, discussing absorption in the For You page.

Focusing solely on the image here — although I think sounds, haptics, and language blur into images, and I imagine what happens to them is fairly similar — it seems like we have a kind of re-embedding of an image into a hereness and a nowness, the constant present of the scroll’s flow state. But at the same time, we have retained a “testing” posture to the image, in that it arrives specifically for us and the platform requires us to test and evaluate it (even if that evaluation is just a “no, next video please, swiping away.”)

I suppose this leads into a larger question — whether what you’re seeing on TikTok is still film. It is a video, but on top of that video is a scrim that allows you to type a comment, choose to support the creator, save it to your archive, or share it with others instantaneously. Around that video are interaction counts, an endless scroll of other videos, and all the other functions of your life — everything from banking to sexting to ordering food to professional emails are just a finger’s tap away, and in the form of a digital profile that exists across platforms, it is all interconnected with what you see on the scroll.

What ties the visual experiences of the scroll together isn’t primarily a relation to time (in the form of continuity, simultaneity, or narrative), or to space (in the form of adjacency), or to other people (in the form of organization and community) but a relation between the computer, you, and the piece of you that is inside the computer.

This is one reason why I’ve often felt weird when people ask me what a meme is. Conventionally, we think of memes as images and texts, as videos and audios — but it seems like what we’re really playing with is this relation between computer, you, and the piece of you that is inside the computer. The image, sound, clip, text, or whatever it is just is the occasion to dredge that up, the real artistic medium is the web that knits the self, the computer, and the piece of the self inside the computer together.

III. Algorithmic Gaze, Layered Images, and Informational Contingency?

Returning to Benjamin — and that essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Production (1935) seems to reward me every time I return to it — one thing that struck me in his analysis of the camera (which I guess can only really come to you if the first time you see a movie is when you’re in your twenties) is his idea of “unconscious optics”:

Even if one has a general knowledge of the way people walk, one knows nothing of a person’s posture during the fractional second of a stride. The act of reaching for a lighter or a spoon is familiar routine, yet we hardly know what really goes on between hand and metal, not to mention how this fluctuates with our moods. Here the camera intervenes with the resources of its lowerings and liftings, its interruptions and isolations, it extensions and accelerations, its enlargements and reductions. The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.

By decontextualizing the image from time and space as we experience them, the camera makes us aware of what we habitually don’t see in our real, actual visual experience.

In the age of the algorithmic apparatus, there is another variety of unconscious experience which a machine makes us conscious of. I might call it the contingency of images and information. You see the image that arrives at your screen as the result of things you did before, people you have a vague idea of, and systems, processes, and intentions that are always humming in the background. The unconscious process which the computer apparatus makes us conscious of is the fact that there is no such thing as a direct unmediated experience or an objective stance, that images are the result of actions. Something about the granularity, immediacy, and intimacy of the algorithm and interface makes it so we see stuff in a way we don’t when we read a book or watch a movie. We see that the world is never just reported, even by machines that appear to objectively record what happens — instead it is presented, recommended, and framed. The content of an image online is never just what it is of, but who it invites us to be as we look at it, and the way it found us.

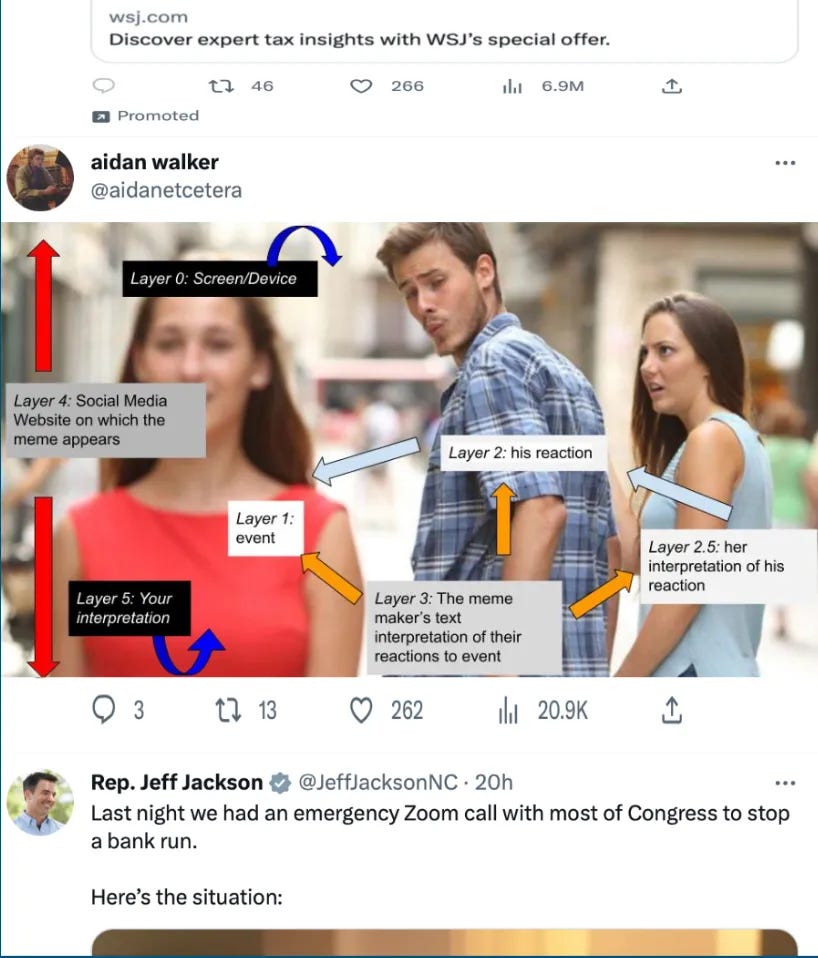

It occurs to me that I have made this point before while talking about how memes are layered, one of my continual fixations in this newsletter. When encountering a Distracted Boyfriend meme made in 2025 on X, part of what you’re doing is reading the algorithm’s take on a 2025 meme-maker’s take on a 2017-meme maker’s take on a 2015 stock photograph:

…this kind of internal structuring, which results from choices made by people as well as conditions imposed by technology, alters the way we think about stuff. In the same way reading too many novels might give you “main character syndrome,” a communicative form that encourages you to employ the comparison of one take, time, or social context against another as the primary way of finding meaning does make you think differently. In a meme, meaning is structured as relative rather than absolute, multiple rather than singular. This differs significantly from the kind of meaning you get from non-meme images or texts which live on other interfaces (page, picture-frame).

I said a few paragraphs ago in this post that what ties the disparate visual experiences of the scroll together isn’t primarily a relation to time, space, or other people, but a relation between the computer, you, and the piece of you that is inside the computer. I should clarify a little and say these relations with time, space, and other people, rather than being absent, are mediated through the relation between the computer, you, and the piece of you inside the computer — which is primary because it happens first, not because it is the most important.

If the “cinematic gaze” is the result of what the camera does to our visual experience of time, space, and social reality, then the “algorithmic gaze” is the result of what the triangulation of computer, you, and the piece of you inside the computer does to our visual experience. The evidence of what the algorithmic gaze feels like, or looks like, lies in the tangible forms we encounter of interface and algorithmic recommendation, of which I argue the layering structure is one of the most important.

IV. Open Questions

This post has already gone on far too long. But there are many things I should address at a later date. Maybe you have input that can help me think about them — please comment if you do. Here are the questions I still have:

Even if the relation is primarily between the computer, you, and the piece of you in the computer, other people still really matter in memes. A meme wouldn’t be a meme unless a lot of people participated in it. This is something to ponder — am I too focused on individual experience here?

What are the consequences of the algorithmic gaze?

The piece of you in the computer is not all of you. If you remember my post on stock photo memes, or my YouTube video essay on the same theme, I talked about an “algorithmic gap,” where humor or meaning emerges from the friction between the generic renderings of the algorithmic apparatus and what the world actually looks like. How to deal with this gap? Does cinema have a similar gap?

There is more to be said about sounds, clips, and language. Does the computer apparatus extend them in the same way as images, or is it different?

In cinema, there are many different styles, some of which are tied to tech (e.g. black and white versus color) and some of which are tied to choices by producers, artists, and the market. Could we do a similar analysis of algorithms/interfaces, looking at different styles or types?

At the end of his essay, Benjamin makes a series of political points around mass media and politics — his famous formulation that fascism is sort of a result of mechanical reproduction, and “fascism aestheticizes politics,” while communism should respond by “politicizing art.” Can we do a similar analysis of current tech?

The point at the end is so important and weirdly prescient that I was thinking about exploring it in an entirely separate post. What are memes like "brat" and Trump serving McDonald's if not the aestheticization of politics, brought to us as viral algorithmic memes? When we view political content through the same gaze as all other "content," how does that affect us as viewers?

I reaally enjoyed this piece!! Some of my thoughts:

I thought the choice to look at TikTok scrolling as a merely visual experience was interesting, and even though it didn't limit the analysis that much (you also acknowledge that the language, sounds etc probably are effected similarly) I couldn't find a particular reason to do that singling out, other than the main anchor literature of this piece being Benjamin's exploration of cinema and cameras. I think TikTok videos are much more than a visual experience, and the algorithmic work that is done there that makes us conscious of a process wouldn't work if the content we were consuming was just visual rather than hold a lot more substance to it like messaging etc, so I felt your analysis applied to the other realms as well, the technicalities of them perhaps different, but still.

I really enjoyed the triangle of you, the computer and the piece of you in the computer, but the thought about memes made me think -- we use memes as a tool of humorous communication in most cases, an easier format of communication to pass an intended message while signaling to a common cultural text (kind of like language, it is a tool (though I need to read more of your stuff to see your take on memes!!) ), so I had a hard time relating it to that triangle -- it made intuitive sense with the algorithm, but with memes I think they can't be seperated from the collective. Not saying the personal shouldn't be thought about, but as memes exist, I think they are far more cultural than a what a personalized tiktok feed is. The algorithm and the vids it brings us has layers that tie us to other people as well, but after all, it is our part that lived in the computer that did the bringing. Memes have general cultural standing, kind of transcending algorithms and the personalization that limits the feed -- people from all corners of the internet know a lot of common meme formats, what they do with them differ, but they do know them.

These are quite unfinished and first reactions to the text, but wanted to note them down before forgetting. Glad to have found ur corner of the net, really enjoyed reading this :)