stock photo memes and the algorithmic gap

the meaning of "generic"

Above: audio version of this post. Below: YouTube version

If you want to know what algorithms feel like, look no further than stock photographs.

Several of the most famous memes started out as stock photographs — posed images sold on an online platform, which companies can buy a license to reproduce and then use in advertisements or blogs.

The draw for meme-makers is evident: these images are bizarre and funny. But they’re also perfectly turnable, meant to work in a variety of commercial contexts — which means they also work in a variety of meme contexts. They are extremely accessible, meant to be rapidly understood by people walking past a billboard or Xing out of a pop-up. And they are uncanny.

Nobody has ever actually walked in a meadow, drunk a bottle of water, or had a headache like the people in the photos below, by Distracted Boyfriend photographer Antonio Guillem — but the images correspond precisely to the mental images you might have — or are expected to have — of these things.

You might say stock photos are portraits of stereotypes. Or that they depict a kind of hyperreality, our idea of the world rather than the world itself. Photography scholar Paul Frosh, one of my favorite scholars of digital images, uses the term “generic” to describe their aesthetic.

Stock photos are like the store-brand version of an iconic product, the ketchup bottle that looks just like Heinz but says Walmart instead (often, this kind of ketchup would be illustrated with a stock photo on the label). It is a weird aesthetic, shorn of ambiguity and particularity, looking like nothing further or lesser than what it is supposed to look like.

Early memes around stock photos make fun of the genre’s weirdness. The Tumblr blog “Awkward Stock Photos,” which flourished in the early 2010s, pointed out the uncanniest among them. Often, there was an “isn’t capitalism ridiculous?” kind of angle to this posting. Part of the political valence of stock photo memes came from using images for free that you were supposed to buy. The watermark, which comes with many stock photos, helped to signal this.

Another part of the political valence came from exposing the biases and sexism inherent in those “generic,” expected mental images of people and things which stock photos depict. In 2011, feminist blogs like the Hairpin pointed out the stock photo’s propagation of strange gender stereotypes, particularly the multitude of stock photo images of women eating salad. Meme-makers recognized that the “generic” image stock photos represent isn’t necessarily the best, normal, or most ethical image of the world we might hold.

2011 saw the “stocking” trend, in which users recreated stock photos at home, to emphasize the absurdity of the poses. This remediation of generic stock photographs into very personal posts representing the body (and also the wit) of the subject is another reading against the grain of the image.

“Stocking” is funny because stock photos are perhaps the only genre of portraiture that is supposed to be a picture of nobody. Scrubbed of collateral meanings and presented in a frank straightforward spirit, a stock photo feels pleasantly clean, in a way nothing seen in real life can ever be. They represent not the reality of a given thing, but the average of expected mental representations of that thing. Every human in a stock photo stands in for “humanity” in general, becoming specified only in the broadest of senses — as “child” or “elderly person,” as “woman” or “man,” as “construction worker” because she wears a yellow hat or “office person” because he wears a tie.

And the stock photo is held on a tight leash by the words which naturally come to your mind to describe it — which are also (usually) the words with which it is labelled, and the exact description it was posed, taken, and edited to fit.

The relationship of the stock photo to language is baked into the way they are made and sold. These are photographs built to precisely match the text in search queries, captions, and categories. The main platform for stock photos is Getty Images, which dominates the market like Amazon dominates e-commerce. Getty Images connects freelance photographers with their clients in the same way that Uber connects drivers with people who need a ride, or Substack connects content creators with audiences. It is a platform, which economist Nick Srnicek defines as “digital infrastructures that enable two or more groups to interact” and position themselves both “between users, and as the ground upon which their activities occur.”

Some of the money made by platforms comes from their position as middlemen in transactions, but they actually end up making much of their revenue from the data they collect, from being “the ground.” Because they set themselves up as the frame and setting of all interactions, recording every detail of what happens, they are able to produce and sell ever-more sophisticated representations of the market. Knowing more about the market, they are then able to shape the market to serve them. This gets even easier as the platform gets larger and monopolistically engulfs more of the market. The more of the market a platform encloses, the more data it gets, and the higher the price of exiting becomes for consumers. This is what Cory Doctorow has described as enshittification: after a certain point, the incentives no longer push platforms to make good experiences for users, but to entrap and squeeze everybody.

The enshittification spiral can be sustained for a long time, because as platforms like Getty shape markets, they fall into a kind of bizarre feedback loop. The platform’s source of knowledge about the market is its data collection, which can never be complete — you can never record everything. And the data you do record has to be organized according to a set of criteria that sort it, rank its relevance, and emphasize or de-emphasize the relations between different data points. Further, that data also has to be gathered, which means it has to be looked for, often by an algorithm taught on its own set of data.

And so, once a platform holds the entirety of a market in its clutches, it starts to impose its own programming: Increasingly, the conditions of the platforms become the conditions and bounds of that market. Anything that happens outside what the platform permits or can understand might as well be written in a foreign language, because people always have to speak to the platform first and to their buyers or sellers second. The only things that can functionally be real on a platform are things that the platform can sort and understand. Which means there remains this awkward, uncanny gap between the reality people live and feel and the allegedly-entire representations of reality created through the platform process.

Stock photos live precisely in that gap, and memes about them are the clearest visual representation of what the gap looks like. The “generic” aesthetic — which is the aesthetic shared by stock photos and AI-generated images — is what a platform sees the world looking like. The measure of the platform’s power lies in its ability to command conformity with that aesthetic.

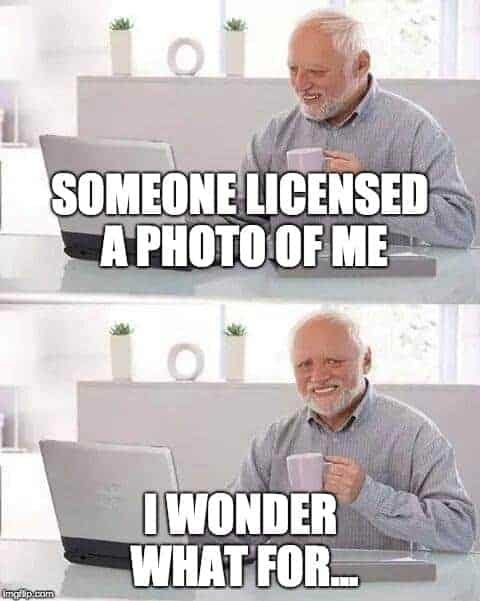

In mid-2010s memes, you can observe a trend towards reading stock photographs with a less explicit hostility towards the genre. A Hide The Pain Harold or a Daquan meme are, on their surface, more about the imagined characters rather than stock photography as a genre. However, they perform what may be a deeper subversion of the platform’s visual regime by turning the photographed people into characters with lore, refusing to understand them as “generic.”

Memes using stock photographs are attempts to specify the generic — to muddy up the stock photo, mark it with a human touch, and create an alternative set of interpretations around the image. Ironically, a stock photo meme really just plucks the image out of one platform and plops it into others, where it undergoes a similar process but as a meme rather than as a commercial image.

At this point, I’d like to go out on a limb and say something that I can’t prove. It is kind of from Michel Foucault. At the core of every platform is an archive of data. In the conventional way we use “archive,” we mean a collection of documents, of inscriptions of whatever kind (whether strings of text, images, parcels of code, whatever — I use the word “inscription,” but I could perhaps also say “trace,” but I want to get across the fact that it’s intentional).

But the archive is also the apparatus by which these inscriptions are organized and made accessible. For Foucault, an archive is the “conditions of possibility” for discourse: not just what is allowed to be said but what is allowed to be heard, and what can even occur to you to listen for or say. This means the processes by which inscriptions get lost or preserved, the interfaces they’re presented on, the classification systems that sort them, any kind of content moderation or censorship that determines the archive’s contents, and the political-economic incentives behind the act of inscribing things — that’s all archive.

This, to me, mirrors the self-cannibalizing enshittification cycle: as platforms dominate an area of human activity, their own methods for recording and representing human activity make the conditions of possibility for future activities. A Foucauldian account of the archive sees science or the state working the same way as Getty Images: you create categories like “insane” or “woman eating salad” to put certain kinds of bodies into, and then these generic, discursive descriptions become stereotypes, heuristics by which people act on one another. Like in urban zoning, descriptions of the social world prescribe certain uses of that world, and pretty soon those descriptions become a lived reality: a neighborhood, a form of development, the pretext for treating the land or the people on it a certain way.

Brilliant read as ever!

Here’s my half baked thought on the lorification of Stock images. Forgive me if all of this is kind of obvious! There’s a clear overlap between the (as you said) hyperreality and generalisations made by both stock images and AI images.

I’m trying to think what captioned ‘AI Slop’ memes there are, and im drawing a blank. I say slop, because there are heavily authored genAI memes (eg ‘Presidents Playing Minecraft’, which I guess is its own form of hyper-reality) which aren’t really comparable to the equivalent ‘Stock Image Slop’.

Maybe the internet had its fun with soulless images in 2011? Maybe it’s because AI images are typically ‘one and done’, never to be reused? Maybe we cant humanise the ‘people’ in AI imagery? I suppose our relationship with soulless AI images is more complex than with stock images.

Very interesting indeed. Thank you.