audio version of this post. most will not be this long.

There’s a TikTok where a lady with a wonderful Southern accent points her phone camera at a mirror and earnestly orders, “Go ahead, say it. Say the weird thing.” She stands in a living room of some kind, eyes wild and delighted. Millions of people have stitched with that post, supplying their own weird thing. I want you to imagine that in your head, and then listen to this:

Nobody has access to real reality. All we have are subjective experiences which, whether actual or imagined, are always conditioned by who and where we are. We exist in the context of all in which we live and what came before — and there is nothing beyond the context, there is not even a coconut tree to fall from.

However, this context and ourselves within it don’t just fluff around willy-nilly. There are discernible patterns and structures to consciousness, which can be discovered through a rigorous method. That is the project of phenomenology, as I understand it.

This post is a continuation of my last post, where I talked about a definition of “meme” that centered on the literal things we experience on a screen. I realize now that I was seeking to define the phenomenon of a meme, grounding it in perception and experience rather than, as the classic definition from Richard Dawkins goes, an analogy to biology; or as I think people in philosophy or the social sciences tend to do, a deep awareness of larger systems and structures. My view is that starting from the phenomenon, from within our subjectivity rather than outside of it, is a useful method.

A meme, as a phenomenon, is a group of collectively-authored online media pieces with at least one mostly-constant part (like the shared image) and one mostly-variable part (like the changing text). Memes, as we experience them, rely upon particular operations of technology, interface, and communities. There is no such thing as a meme outside of those contexts, and the relationship between them goes both ways: memes shape those contexts (whether it’s social media, an online community, an algorithm) just as those contexts shape memes. Through the way memes present or enable things like self-reflection, person-to-person communication, and narrative, they structure how people live and act within their historical situations. The same is true of any kind of art.

Usually, I would stop right there and get into questions about that historical situation directly: like, how are Wojaks used, and what do they represent for modern people? How does the circulation of a meme on TikTok testify to the way the algorithm feels? These are the sorts of questions they teach you to ask about literature or art history. You can take a meme and say, “how can we learn about capitalism through this?” the same way you can with a novel.

But when you close read a meme and see it from a phenomenological or literary way, what you learn about capitalism (or anything else) is never a clean answer. Art lives in ambivalence, like we ourselves do. Literary texts are not factual accounts. Instead of learning how the world is, we learn about how it is experienced by others and ourselves.

And that’s why art is, in a sense, truer than science — because nobody can actually know how the world is, only how it is experienced. It’s like how you can never get an accurate 2D projection of the globe onto a map. Instead, you have to choose what kind of distortion you’ll accept: are you okay with exaggerating landmasses of the Northern Hemisphere (a Greenland the size of Africa, like in the Mercator projection) or would you prefer the oceans between landmasses shrunken and distorted (as in a Robinson projection)? Our sense of how the world is should be considered a function of how we experience it, rather than the other way around.

There’s a poem touching on this topic from some point in the 1620s by English cleric John Donne which I love, where he’s talking about lying on his deathbed:

I joy, that in these straits I see my west;

For, though their currents yield return to none,

What shall my west hurt me? As west and east

In all flat maps (and I am one) are one,

So death doth touch the resurrection.Donne imagines his body as a map and his death as the western (sunset) edge of the map. But since he’s a Christian and believes in the resurrection and eternal life after death, he chooses to see his body and life as spherical, without limits or edges. His sunset leads into his sunrise.

The flat map doesn’t show us that the world is round. Instead we must round the world ourselves by choosing to see the flat map a certain way, purposefully perceiving something that is not there in front of our senses. For Donne, believing the flat map represents a globe is like believing this life, as lived through his body, represents a grander order. Faith in the resurrection, in Donne’s poetry, is a symmetrical process to interpreting a drawing or a sentence. The phenomenon you literally experience while doing that is seeing something that is not there.

This operation could also be called suspension of disbelief. The map, like a poem or film, requires a form of imaginative engagement to express anything to us. Such an engagement can’t be thought of as a “choice” to believe, because we never see a thing without making some form of imaginative investment.

While it isn’t always quite as literal as a map’s edge, all art (including memes) has some equivalent point in it. When I look at abstract art that’s just splatters on a canvas, I think it’s about poking at that point. And memes do the same.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the famous phenomenologist from the 1950s, says:

Since perception itself is never complete, since оur perspectives give us a world to express and think about which envelops and exceeds those perspectives, a world which announces itself in lightning signs as a spoken word or as an arabesque, why should the expression of the world be subjected to the prose of the senses or of the concept? It must be poetry; that is, it must completely awaken аnd recall our sheer power of expressing beyond things already said or seen.

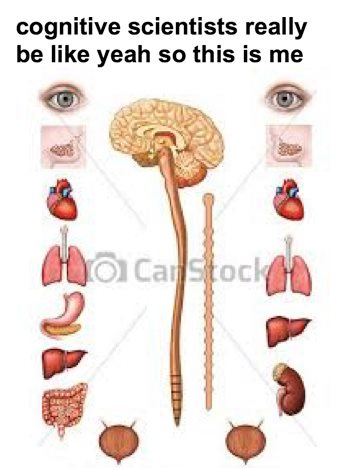

Merleau-Ponty says he aims to save philosophical thinking from two different forms of “prose:” the “concept,” meaning abstract rational systems which imagine a world that exists independent from our perception, and the “senses,” meaning the opposite, a solipsistic world that exists only as a consequence of our senses, which denies the existence of what can’t be seen. He sees a rigorous study of “perception” as the middle-ground between the two.

Perception arises from the body, but Merleau-Ponty doesn’t mean “body” in the sense of arms, legs, and face. Instead, the body is always a “being-towards” something, it’s always experienced in motion and through its relationships. So, the body is your belly and skull, but it’s also the structured ways in which your form is perceived, received, and treated by the world. By this definition, I think you could see images and algorithmic profiles of yourself as extensions of the body. The body is experienced as both “senses” (physical parts) and “concept” (socially-constructed parts). Experience always extends past literal isness.

Returning to John Donne, part of what makes his poetry so moving to me is an appreciation of the body as both “senses” and “concept.” He gets to the flat map metaphor by talking about how he’s literally lying flat on a bed and the physicians are examining his body like scholars would examine a map. “Senses” and “concept” are not opposites within Donne’s body, but constitutive parts, leading into and through one another.

In his essay “Cezanne and Doubt” (which is such an amazing essay, you should read it) Merleau-Ponty says we often “substitute for our actual perception what we would see if we were cameras” when we talk about visual phenomena. We imitate machines and abstract representations, living by reference to “concept” rather than our own experience. Merleau-Ponty’s take on Cezanne is that Cezanne does the opposite, not showing the visual world as it exists but showing it as we experience it, which is really the more relevant thing to examine.

Merleau-Ponty, talking about Cezanne, says:

A successful work has the strange power to teach its own lesson. The reader or spectator who follows the clues of the book or painting, by setting up stepping stones and rebounding from side to side guided by the obscure clarity of a particular style, will end by discovering what the artist wanted to communicate. The painter can do no more than construct an image ; he must wait for this image to come to life for other people. When it does, the work of art will have united these separate lives; it will no longer exist in only one of them like a stubborn dream or a persistent delirium, nor will it exist only in space as a colored piece of canvas. It will dwell undivided in several minds, with a claim on every possible mind like a perennial acquisition.

Again, this idea of experience through senses (“a colored piece of canvas,”) paired with experience through concept (“stubborn dream or a persistent delirium.”) But there’s also a kind of gesture towards experience/perception as fundamentally social, which is also the condition of our bodies, always in relation: “the work of art will have united these separate lives.” It is in the process of perception that the work of art lies rather than in its product.

A meme is constantly in process, constantly under construction. By its circulation, it unites a series of different lives. A meme does not mean in any explicit one-to-one sense, but rather it waits for someone to make it come to life. It expresses, generating an experience rather than a data point or a conclusion.

Merleau-Ponty grounds his reading of Cezanne in an understanding of vision and the techniques of painting. By working with color, line, and shape, Cezanne embodies — and plants within the viewer’s body — the process of seeing and, perhaps, the landscape itself. In memes, there is certainly a visual component, but the machinery at play is really the constant part set against the variable part. Another way to articulate this might be the communally-shared part (the image everyone uses) against the individual part (the text you supply). A meme, as a process, expresses the meeting of individual with community online, in the same way that a painting, as a process, expresses visual perception.

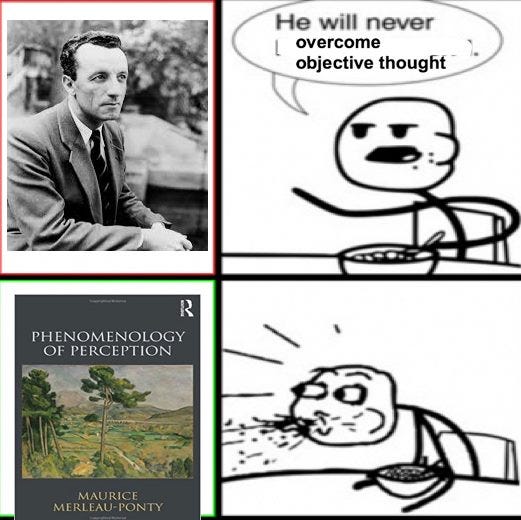

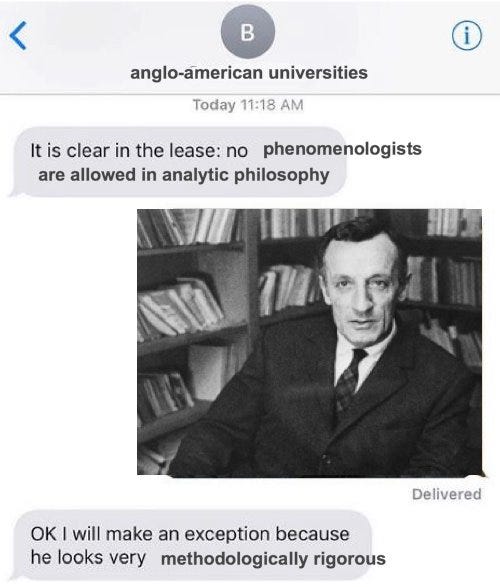

Take, for example, this meme about Merleau-Ponty from the Facebook group of Merleau-Ponty memes I discovered. The meme format this participates in comes from 2018, and the original viral version (seen below) showed a cat. The mostly-constant part is the phrases in gray text bubbles and the screenshot background. The mostly-variable part is the image added.

Everybody who knows a landlord understands the vibe of this conversation, and I think you could read the meme format as a commentary about human connection under capitalism. We see a certain dehumanization of Bruce, treated only as instrumental (no last name in contact, only “landlord”). We also see Bruce behaving like a jerk to the speaker (presumably you, because the gray text implies he’s texting you and we usually see this kind of screen in personal correspondence). But then, suddenly, Bruce Landlord behaves in a very compassionate way upon seeing a cat.

There is a fantasy baked into the mostly-constant pieces of this format about forming bonds beyond the limits imposed by an economic relationship, convincing someone with power to make an exception in a world run by so many rules. This format is anchored in that collective understanding of vibes and context.

In the Merleau-Ponty repost, we see the meme-maker add their own text in a way that is purposefully awkward, with letters reaching past the bounds of the bubbles. This awkwardness of fit, where the speaker or individual’s self seems to overflow the containers provided by the communally-shared format, represents a feeling of being “too much” — which, for committed stan pages like this one, and theorygram-type content in general, is one of the key emotions: “I’m not like other people.”

At the same time, there’s a positive side to this: if the community is represented by the shared format and the individual by the user-generated portions of the meme, then this meme — like many others — shows people making the communal forms work for them, proudly taking up space and claiming ownership. So many memes show their seam in this way, making it clear where the meme’s we ends and the I begins, offering an appointed role and space for those who want to play along while recognizing the framework in which they have to play.

The experience of a meme is fundamentally an experience of attachment. First, in the literal sense of attaching your own body, thoughts, or spin to a pre-fabricated template. And second, in the sense of attaching your body to other bodies, or at least to the computer-mediated systems that embody social life today.

I feel like Introduction To Phenomenology did not prepare me for this

Coming back here to agree, this article needs more attention