Memes have a way of crossing and confounding borders, which is one of their best qualities. A look through the origins and viral trajectories of some of our most popular memes indicates a deliciously cosmopolitan flow:

Wojak, for example, was first drawn by a Polish user on a German language forum and popularized on an American platform named after a Japanese website. Skibidi Toilet was created by a Russian national living in Georgia and participates in a predominantly English-language machinima meme tradition on an American platform. Distracted Boyfriend is a photo taken in Spain and turned into a meme on US Twitter, with the first viral post reportedly made by a German-language user. The list of possible examples goes on and on.

This cosmopolitan flow means memes can be studied as informative historical artifacts. Memes indicate the way digital publics are knit together, the way ideas travel from one place to another, and how people feel about the rest of the world. Memes and their reception are trackable (through metadata, like counts, reposts, etc.) in a way many traditional cultural artifacts are not (making memes a doubly interesting type of source). The aspect of our times which memes maybe speak to most compellingly is the globalized interconnection of culture.

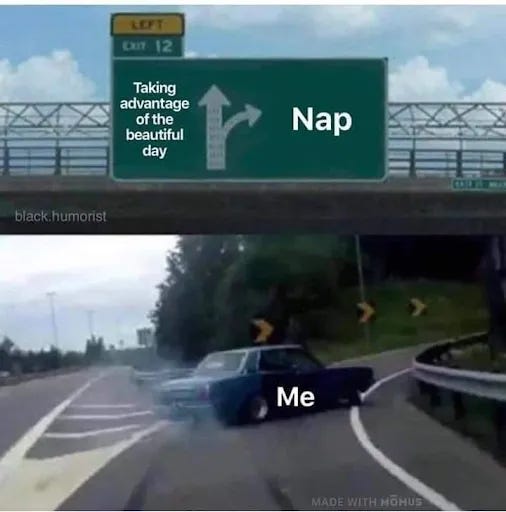

Take, for example, this French meme that remains one of my favorites, which I covered a while ago.

The first sign on the left says “Use (meme templates) which participate in American soft power,” and the second sign on the right (marking the exit which the car takes) says “Remake a meme for our home.” The meme shows a very French car (a C15 Citröen) on a very French road (the speed limit is in kilometers, the highway signs are in French with blue and white letters).

The format this meme references is below, and you’ll the road sign is in English and green with white letters, like they are in the United States. So memesdecentralises literally did remake the meme format for France rather than participating in American soft power.

But look at the sky below the bridge and compare it to the sky above the bridge. As Know Your Meme documents, the bottom half of this image actually comes from a Norwegian YouTube video, with the American road pasted on top, and was first used to make a point (in English) against the Swedish government’s immigration policies.

And this brings me to another reason for studying memes and documenting these circuits of cultural cross-influence: we need to demonstrate respect for others.

So many people around the world, including my own government, want to deny their fundamental connection to other cultures. The current administration in the United States campaigned on saying Haitians eat dogs, Europeans are cowards, Mexicans want to poison you with fentanyl, and certain countries are “shitholes.” Any American has an ethical obligation to oppose this kind of rhetoric and the policies that accompany it (like shoving people into camps where abuse is sure to be rampant).

Any chronically online person also has an ethical obligation to oppose this bullshit. Because if you like memes, you owe a debt to posters around the world who have informed, entertained, and nourished your mind. To not respect them is dishonorable. To not acknowledge their contributions is inaccurate.

Now, I don’t think you can show an Arabic brainrot meme to some AfD goon and convince them to treat their neighbors with kindness. But I do think that making an affirmative case for why other cultures are brilliant and valuable is really important. And it is especially compelling if you can make a case for the contemporary digital forms of those cultures, which are among their most lively, circulating, and accessible parts.

Memes demonstrate the creativity at play around the globe, showcasing the common, complicated humanity of the people who enjoy them. Memes carry on the brave beautiful dialogue in which we and our ancestors have been enmeshed ever since bands of nomadic hunters and early agriculturists first exchanged pottery and seashells on the prehistoric plains, and wayfaring merchants rolled the syllables of foreign tongues through their mouths and ledgers at the trading-posts, souks, and harbors of the ancient world, and voyagers watched with nervous excited eyes as the skyline of a foreign metropolis emerged from pale clouds on the other end of a long horizon.

Such journeys and exchanges are the natural state of human beings — this is the only retvrn-able-to tradition we have. If you grew up on the internet like I did, you grew up in this deeply-connected world, where people from every place and walk of life posted on the same platforms with an unprecedented level of intimacy. You’ve gotta help preserve this global culture we grew up in rather than let nationalist goons yank us into a revisionist fantasy hostile to our traditions, neighbors and values. Call me woke if you want, I don’t give a fuck. God, the People, and the Truth are on our side.

TikTok Brainrot Reflections

Recently, I’ve made three TikTok videos about “international brainrot,” and I intend to make more. The first was about Lakaka, a French-language account which posted memes about cats that were inspired by the format of an English-language brainrot account called Offlain (I’ve also discussed Lakaka in the context of lore traditions ). The second dealt with “Germanrot,” a densely absurdist, reference-laden German-language meme tradition that prominently features pigeons, consumer products, and insanity. The third was about al-Rahma, or “world of mercy,” an anime-inspired Arabic-language meme tradition that expanded into a mobile game and centers around characters borrowed from the last twenty years of internet culture (Big Floppa, Pepe, and Hafoozlik, who as the memes say was a famous footballer).

I am pleased from both a commercial and ideological standpoint that these three videos have over three million views, taken together. People want to hear about international memes, which is good. I’m also happy to develop a workable method of using TikTok for research. I discovered Lakaka on my own, but both the Germanrot and al-Rahma videos came from correspondences I’ve carried on through my DMs and in the comments on previous videos.

In this post and my subsequent ones about international memes, I want to talk about what I’m learning. Our global meme exchange does not happen in a vacuum — rather, it is formed by a convergence of contingent, specific factors, which comparative memeography (like the practice of comparative literature) can shed light upon. Here are three of them:

1. The place of English language

The lingua franca of the internet is English. You see words borrowed or adapted from English across international memes (particularly vocabulary having to do with technology) and you also see phrasal meme templates borrowed from English.

But you also find a kind of ironic reaction against English. In Germanrot (as one of my Deutscher informants told me) all loanwords from English are diligently avoided, leading to a humorously convoluted form of German. In the al-Rahma Arabic memes, phonetically-rendered English is used for comedic nonsense effect.

And so there is a political dimension here, as outlined in the memesdecentralises meme at the top of this post — is meme culture, like Hollywood, American soft power? And how are memes responding to a world where American imperial power is in decline?

2. The TikTok post and Lore as a form

The three cases I studied share the structure of a TikTok post in 2024/2025, which imposes particular boundaries and formal limits — while also offering specific modes of interaction. What all these memes share is retention editing and informational density: they are built to hook a viewer as they scroll along. These memes are also anchored on keywords and central characters, with strong visual gags that don’t need to be translated (anyone could laugh at Hafouzliq or the trademark Taube of Germanrot).

I’m narrowing my study of international memes to the comparative study of “lores” and focusing on TikTok as a platform. So it’s like a scientist controlling for particular variables in an experiment — I believe the similarities I’m seeing between these different meme traditions speak to something happening at the level of interface and algorithm. TikTok shapes stories a certain way, regardless of language.

In each of the meme lores I’ve studied so far, a non-linear web of connections extends across a whole group of posts and certain characters recur, alongside particular themes and fixations. In my previous lore post, I outlined some of the qualities I associate with the medium: lateral movement across an imagined space instead of linear movement through narrative time, plural authorship with a place made for remixes and self-contradiction, and textual authority generated through interaction and mass collaboration rather than tradition or prestige. Each of these conditions derives from how TikTok works as a platform.

A fourth condition, one which I think is essential to most memes, is the velocity of a meta-narrative. Much of any lore’s appeal is the story of its making and popularity. Most user-generated posts around Lakaka lore revolve around people classifying the characters, and self-deprecatingly sharing their weird obsession with these bizarre cats. Similarly, Germanrot and the al-Rahma videos are beloved for being so aggressively random and yet ubiquitously popular on certain sides of the platform. Lore is a bit people need to commit to, and they post about that commitment.

3. Another dialectic?

There is also a key tension at work here, perhaps a generative, dialectical tension like the one I identified in my Skibidi Toilet analyses.

We live in a highly cosmopolitan, free-flowing international memescape, where we often encounter fresh and foreign memes by chance. And yet there’s also a tendency by the algorithms and platforms to put us in echo chambers. How does that work? Can both things be true at the same time?

I would conjecture, first, that we are connected within our echo chambers in ways we don’t realize: many things happening in American meme culture are likely influenced by memes that aren’t in English, but people just don’t know the connection. Algorithmic sorting obscures chains of influence and ongoing conversations as much as it enables them to occur.

Second, we do see a kind of intentional digital cosmopolitanism as a political stance or just as a result of personal taste (for example, the Xiaohongshu migration, or from a less political angle, the international fandoms around Kpop or Taylor Swift). These connections certainly serve to knit together digital publics, and most echo chambers span across languages. Borders drawn by the algorithm contradict those drawn by politicians at least as often as they align.

Third, technical processes like automatic AI-powered translation and the instantaneous flow of information reduce the amount of friction that happens in crossing cultures, even as it also (perhaps) dilutes or warps meaning. So the average French TikTok user is seeing more Spanish-language media and understanding it more easily, than the average Frenchman did back in 1960.

Fourth — and this is the part which may be dialectic — the strength of an echo chamber and its density of engaged users helps build something that’s strong enough to “break containment.” Maybe we wouldn’t have an interconnected international memescape on TikTok unless we also had tight echo chambers in which memes could incubate, do numbers, and pick up momentum. Conversely, we wouldn’t have echo chambers unless we had a mainstream and widely accessible dialogue for them to branch off from. Something to ponder. I’ll get more into this stuff in the next international memes post, which will be paywalled except for a long preview (so if you’re a free subscriber, you’ll get about 50% of it.)

Also, check out my interview with

talking about astrology, Skibidi Toilet, and growing up Gen Z!

Such a good piece - thank you!