six seven

six seven 67 six seven 67 six seven 67 six seven 67 six seven 67 six seven 67 six seven 67 six seven

1. Origins

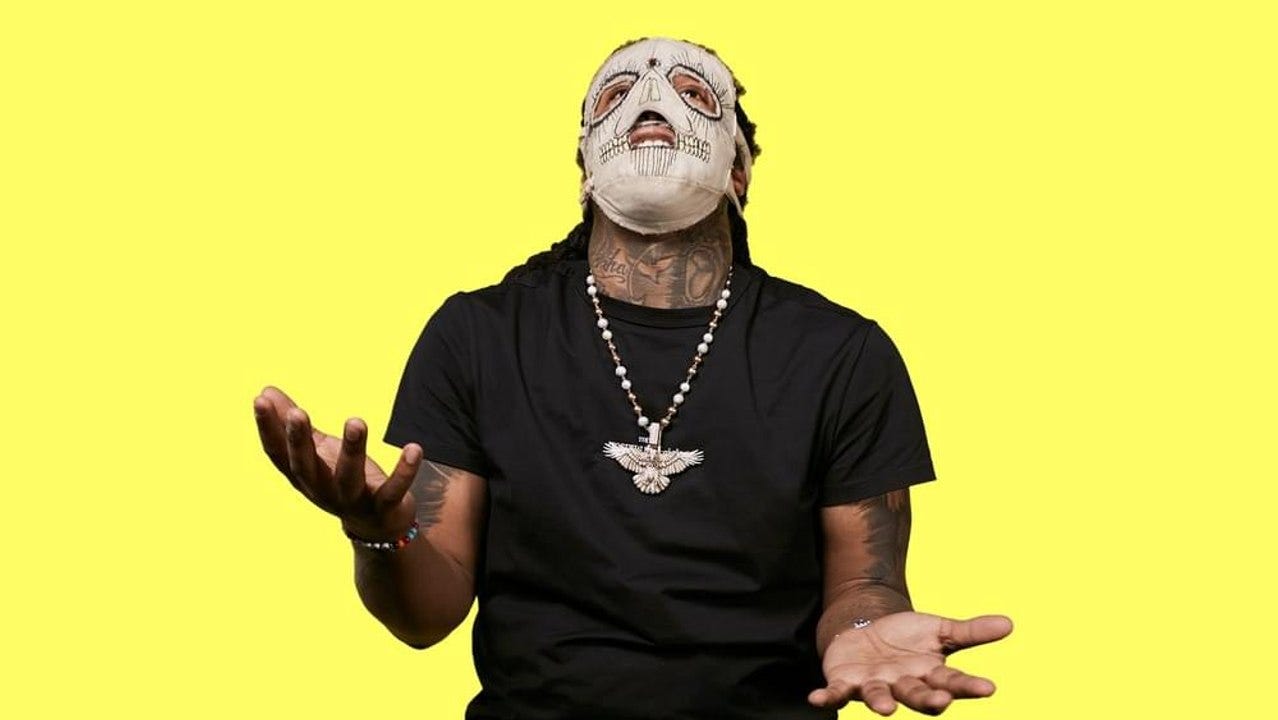

In the beginning, “6 7” was a lyric in “Doot Doot,” a song by Philadelphia-based rapper Skrilla, which came out last winter: “6 7, I just bipped right on the highway.” Almost immediately after the song’s release, “Doot Doot” (in particular, the moment Skrilla raps “67”) found wide usage in fan edits of basketball footage made on TikTok and Instagram. Some of the most prominent of these edits centered on LaMelo Ball, a player who is six foot seven.

From there, the catchphrase spread widely among people posting about basketball on the internet, spurred along by players (who watch those edits) finding ways to weave it into interviews with the press, as well as enterprising creators who posted well-crafted content. Teenaged basketball player and influencer Taylen Kinney became a key figure in 67, adding the hand gesture associated with it.1

This is often the case with extremely-viral memes: First, they reach saturation within an active and established online niche (in the case of 67, people who like basketball) then spread outwards across the broader internet. A process of context collapse occurs here and in many cases — like with 67 — the meme’s spread maps along familiar circuits. With 67, a piece of culture pioneered by Black Americans from a specific place goes national and then international, blurring its original meaning — a pattern of cultural diffusion and appropriation established long before the internet existed.

2. 67 as collision of online and irl

In the spring of 2025, 67 went truly viral. A video of a young white boy screeching “67” at a basketball game went viral, attaching his face and childish enthusiasm to the meme. The “67 Kid” became its own kind of figure in meme culture — an archetype, sometimes “Mason 67” (canonically, the son of Karen, representing a particular social type) but also a kind of emblem for Gen Alpha more generally. And the meme became particularly associated with young children rather than older teenagers like Taylen Kinney, or the adults who participated in making 67.

As posters like Etymology Nerd have pointed out, the 67 meme turned into a kind of public display performed for online clipping: not just at basketball games but in classrooms, at restaurants, at concerts, people did the 67 meme in public in hopes they might be filmed and then posted doing it.

In this way, 67 starts to look a little like the planking trend from the mid-2010s: A meme that crams a performance for an online audience onto a real world stage where that performance is illegible to passersby, to the uninitiated, to normies. The meme lays claim to the real world as a backdrop to an online project.

Planking was optimized for technology and platforms as they existed in the mid-2010s: it consisted of still photos, a viral pose, and no associated sound. 67 meme is optimized for vertical video platforms: it involves a rhythmic motion, a snippet from a viral song, and a trending keyword (or, rather, number).

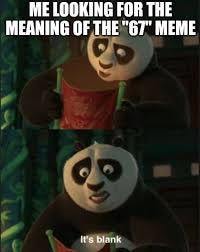

3. Unstamped meaning

Throughout the spring of 2025, the edits continued, the memes flowed, and more and more people were talking about 67. Particular creators — such as Hoopify, of Baby Gronk Rizzed Up Livy Dunne fame — made a habit of promoting 67.

By the summer of 2025, the 67 meme had drifted far from its original context and joined the ranks of previous brainrot words such as “skibidi” and “sigma” — a repeated term that held a meaning more through the fact that it was exchanged than by the fact it referred to anything. Skrilla, in an interview with XXL magazine, explained it this way:

INTERVIEWER: I’ve heard all kinds of theories about what 67 means, from police codes to something that’s gotta do with the periodic table. Can you explain what 67 means?

SKRILLA: That’s why I never really put a stamp on it, though. Because the meaning that I had for it, it was like a negative and… it changed, like 67 changed from a negative thing to a positive, and millions of other things for other people though .. like 67 is, like, everybody got they own meaning to it because I never put a real meaning on it. But 67 actually comes from a neighborhood in Philadelphia, though, a neighborhood in Southwest Philadelphia…

Skrilla’s decision “not to put a meaning on it” is part of what made 67 such a banger. By its vacantness, the 67 meme creates a space for various people to play across and an occasion to connect.

Over the summer, people proposed new “number” memes — 93, 41, and 61 among them, each accompanied by its own hand gesture and way of saying the number, repeating the 67 formula.

67 and abstract art

In a video on TikTok and Instagram, I interpreted the 67 meme as a kind of meta-commentary:

The meaning of the meme is it has no meaning. It’s about what 67 testifies to rather than what 67 is. It’s just a number. But what it testifies to is the power of organized online publics to meme something into relevance, meme it into the minds of actual 67-year-olds, without actually needing it to refer to anything in the real world. Because the thing we’re making viral (seems to be) entirely arbitrary, the meme itself is a more pure experiment in, and illustration of, the dynamics of social platforms. We know this thing is popular because of social contagion because it means nothing, it couldn’t be popular for what it is. A meme like 67 allows us to see those processes, communities, and technologies at play in a way that a meme which is about something simply can’t.

My thinking on 67 is informed by my interest in Language Poetry (also called L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E) a postmodernist poetry movement in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Charles Bernstein, one of the leaders of the Language poets, defined “language writing” as “writing that takes as its medium, or domain of intention, every articulable aspect of language.”

Bernstein and his collaborators wrote poems that were about language, in the same way other poets would write about love or nature.2 Some Language poems are postmodernish parodies of how literary forms work, others do weird stuff like put “=” between all the letters in a word. Often they do mind-numbing repetition, like when you repeat a word over and over again until it loses all meaning and you feel it as just a hitch of the breath, an arbitrary sensation. The poems work to make you see language rather than see through language as you habitually do. Some of them are silly, most of them don’t make sense. What comes to matter is the mechanics of personal encounter with meaning-making. And the poem sets up a moment for you to see that, to celebrate it or critique it.

67, and meta-memes like it, are about posting in the same way Language poetry is about language. The creation of new number memes like 93, 41, 61, and 89 adds to the joke. As posters debate over which number meme can unseat 67, it’s clear there can be no rational reason to really prefer 41 to 67 because there is no content — with 67 there is only context. The meme celebrates and exposes that context, reminding us that it is our mutual involvement in making that context that keeps us human. It is in this way that meta-memes turn us back on ourselves, on the device in your hand, and affirm the power, for better or worse, of screens and the stuff that plays across them.

5. The joy of merely saying

When a six (or seven) year old repeats the 67 meme, what they’re doing is repeating a meme that is a pure meme. It’s not a joke about anything to most of them. It’s just the thing you say and it’s funny because you say it. A commenter on my video pointed out that he thinks his kid likes 67 because, as a young child, his kid thinks a lot about numbers and the naming of things. Adults are maybe too habituated to language, and don’t realize how fascinating it is that I can make a sound with my mouth that I can be sure essentially anyone I meet will understand as referring to a thing neither of us have ever seen. And then I can put those sounds together and get people to laugh, to like me, to dislike me.

If you’re shy in school, you can say “67” and people will notice you in a way that feels safe. If you want to make an adult pay attention, you can say “67” to them and you can play the game of watching them not get it. As you spot the two numbers out in the world and announce them, you enchant a thing that would otherwise be as ordinary as dishwater. And as you open your phone, you see tons of people across the internet saying it too and find yourself belonging to a big club, where all you have to do to be a member is say you are so.

67 should be seen as a great work of art. It might not be legible by the metrics people typically grade and distinguish works of art by. But this collectively-authored, improvisational, joyous cacophony of posts across platforms does have great value. And if you had to pick one piece of art to show to a space alien that just landed in your backyard to explain what humans are like in 2025, you’d be better off picking the 67 meme than you would be War and Peace. Although, ideally, the alien would have time to see both of those things.

six

7. seven

A note on TK — he is a high school basketball player who joined the Overtime Elite league and has since committed to play college basketball at the University of Kansas. The role of the Overtime Elite league’s social media operation in spreading 67 should also not be understated — they filmed TK, edited him, etc.

This is not to say Language poets aren’t interested in other things, or that non-Language poets are not interested in language.

I do think it’s really valuable to view 6 7 and other memes in a lens that isn’t primarily focused on any “degeneration” of the mindscapes of the youth. I watched way too much YTP as a kid for me to ever seriously judge gen alpha for liking tung tung tung sahur

David Crystal talks about "language play" as a foundational way that children experience language. To them, this meme is just that: goofing around with the boundaries of language. "Six seven" are supposed to be unrelated numbers, and it's silly to combine them into something with their own significance. It also helps, of course, that we're constantly primed to see the meme in the world around us