platform presence

the terroir of posting

All roads lead to phenomenology, a word I always fear I will spell or pronounce incorrectly. A recent post by my friend Adam Aleksic (Etymology Nerd) titled what to do in digital stew is worth your read. In that post, he references an idea, “platform presence,” which I started to toy towards in my pamphlet On Skibidi, available via Metalabel.1 I want to think a bit further about what I may have meant by “platform presence,” not just in relation to Skibidi Toilet but to broader topics in internet culture.2

In On Skibidi, I wrote:

People seeing [Skibidi Toilet] are not, generally, all sitting down at the same time to watch and are certainly not sitting down in the same space. As a rule, they are alone when watching. But what they do share is what might be termed a kind of platform presence, the disembodied always-already thereness of YouTube. The maintenance of this always-already thereness is one of the key functions of any social media platform. Most of the work done to maintain it is performed by users, because the platforms are built from posts and audience interaction with posts.

I reference YouTube here because I’m talking about Skibidi Toilet, but the platform I’m really thinking about is Twitter and its clones like Bluesky, Notes, and Threads. People on Twitter are constantly talking about being on Twitter. And there is always a sense of several ongoing discourses prominent enough that at nearly any point in the summer of 2023 you could turn to a friend you knew was also online, say “have you heard of the OceanGate submarine thing?” and know they’d probably have a take. The sense that the conversation is never not going on, and that it’s only going here according to norms, codes, and rhythms that only exist here, is what makes these platforms appealing — and historically unique. It wasn’t too long ago that people said a 24-hour news broadcast you passively watched at home was revolutionary.

This sense of a sustained, all-encompassing conversation is manufactured. Things are rarely getting talked about across all of Twitter, usually just in whatever part of the platform you’re on, your specific “TPOT” (this part of Twitter). And, since there’s an algorithm, once engagement clusters around a particular topic and it starts to trend, it takes on a velocity that a rumor whispered in a crowded room simply wouldn’t.

People tend to explain the way a platform feels, the way its presence touches us, by talking mostly about algorithms and interfaces — and these may be a great part of what makes the internet platforms different from other social spaces, but they are not the only thing that characterizes a platform. Users and institutions are also doing a lot of the manufacturing of a feeling of platform presence. Individual posters making jokes, memes, and comments are the building blocks of the conversation. And in the case of Twitter, there’s a clear feedback loop with media and political institutions: All the power players are on Twitter, and because of that Twitter becomes a place where the games of power are played.3 They find leads and take the world’s temperature by following conversations on the platform. If they’re partisan, Twitter provides them with who they will be arguing against. The platform’s vibe creates the conditions for our participation in conversations on it; and consequently for our participation in the markets that are rooted on it; and in a broader sense, for our participation in the reality that runs out from it.

Aleksic’s metaphor for being online is stew, and he brings up the idea of “perpetual stew” — famously promoted by that awesome Depths of Wikipedia girl, creator Annie Rauwerda. A stew can boil for hundred of years if new ingredients are continually added and the heat kept on — several documented historical instances of this exist. That’s what Twitter, TikTok, or any platform are — a perpetual stew. New things are tossed into the broth each day, as the soup is steadily consumed, but the flavor is rich and hearty from the traces of all that was in it before.

Agricultural metaphors come to mind as well. A social media niche is a productive piece of digital real estate. My takes grow on TikTok like merlot grows in a particular terroir; my slant on reality conditioned by delicate fluctuations in algorithmic happenstance, identity, and audience preference — just like wine grapes are characterized by sea breeze, soil minerality, and the heat of an unusually dry August.

Part of why I appreciate wine is that it’s evidence of people really paying attention to nature. The vineyards in France understood something was up with the climate years before scientists did (or so they’ll tell you when you go on a vineyard tour). Wine is human adaptation to specific terrestrial conditions — some nature-made and some man-made — and so is content. But unlike a wine bottle, a TikTok video is responding more to human-made and automated conditions than natural ones (although I suppose brain chemistry does play a part). Just like the millennias-old track of a glacier will make the wine sharper, the decision implemented by some sorting algorithm or goofy teenager in Slovakia will make the brainrot danker.

This wine metaphor has gone on too long and I don’t really know what I’m talking about, to be honest. But what I mean to say by it is that platform presence is the making not just of content but the conditions under which content is produced. Elsewhere in On Skibidi, I describe it this way:

[The anime pfp accounts which deranged Elon and his ilk] created that sense of platform presence, a “there” on Twitter, where people were and where important ideas lived. The maintenance of that thereness amounts to a process of soft institutionalization: prominent accounts link together, collaborate, fight, and coordinate.

The point I was trying to make in this part of On Skibidi, which I also try to make across my content, is that people assign too little agency to posters, whether with anime pfps or not. I am not calling for some Great Poster Theory of the Internet: structural explanations do play a role. But public conversation too often slides into the image of a computed social sphere which The Matrix presented us: a bunch of brains in jars, helplessly manipulated by big companies and addictive tech. I don’t find this image to be factually true, but even more importantly, I don’t see it as politically useful.

Instead, I think we should see the internet as a series of terroirs — patches of productive cultural space through which different forces work, and upon which we are able to act both individually and collectively. The farmer can spray, fertilize, and make choices on what to plant, when, and how. The community (or state) can undertake public works that irrigate land, conserve resources, protect the bees that fertilize, and underwrite the legal and financial instruments necessary for farmers to work the land profitably. Our current forms of platform presence are the result of a particular kind of stewardship practice and exploitation. We could choose otherwise.

But in a sense, the terroir metaphor is wrong. The conditions of platform presence are not primarily natural givens to which people adapt, but social/technical constructs which are imposed on us. And this is all the more reason why the way people currently talk about the internet is so stupid. It would be very possible to have an app to share pictures with our friends that doesn’t have a seventeen-strike policy for sex trafficking, as Instagram did. It would be very possible to do e-commerce without immiserating communities and skipping taxes, as Amazon does. That our public conversation about the internet seems not to allow other possibilities is the failure of imagination from which all our other failures spring — another instance of Frederic Jameson’s maxim that it has become “easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism;” it is easier to imagine the end of the internet (as Al Jazeera asked me to do in a recent interview) than the end of corrupt social media platforms.4

I have drifted far from what I started out meaning to say.

To return to the thread, I want to offer that analysis of memes (and internet culture generally) should shift to the conditions of possibility — to what’s in the stew, how it got added, and how the flavors layer together, which is why a phenomenological turn is a good thing. Memes are specific moments where an algorithm, a human(s), an audience, and a device met. Just like any other art object or bottle of wine, they are a record of human intention meeting with an environment that it altered and was in turn altered by. The Rothko hangs in the gallery as something Marc made, but also as paints mixed in a factory, canvas stretched, and a moment in my life as I pause and try to make myself feel moved because the brochure says it’s important. By understanding the resulting combustion when you bring all those things together, we understand ourselves better, and by that understanding we take back some measure of control over how our lives will go, or at least feel — and in so doing, start to remedy that failure of imagination.

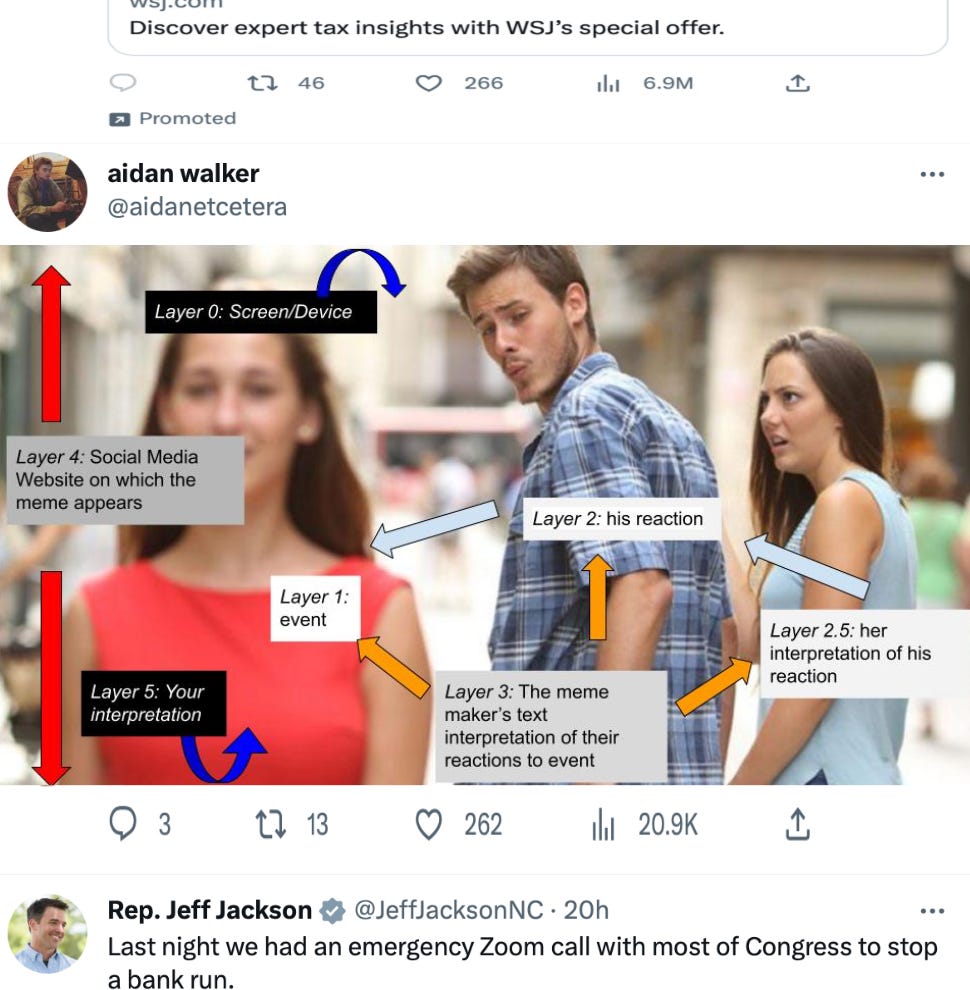

In my Master’s thesis on Distracted Boyfriend, I sought to tease apart these different influences as components on the meme image — I saw them as layers. Someone puts word-labels on a stock photo, turning it into a meme. Someone puts new words on top of the labels which fit the same structure, making the meme into a format. Someone copy-pastes it into a text field and presses enter, turning it into a post. Someone else presses the little arrows button below it, turning that post into a repost. The algorithm latches on, finds you, and turns that repost into a thing on your feed. And you like it, turn it into a memory. Each layer of the image holds those different contexts, and the meme makes a point by moving between them — by illustrating its own conditions of possibility and denaturalizing them.5

Victor Schklovsky, the Russian Formalist critic, described the writer’s mission in his 1917 essay “Art as Technique” as one of defamiliarization, to make experience appear fresh again, shorn of the habits we typically shroud it in. He says the writer’s duty is to “make the stone stony,” and I underlined that in my intro to Critical Theory class in undergrad. The meme is there, I think, to “make the post posty.”

I will send paid subscribers a free print copy if you request one via this form — planning to start getting them out to you sometime in the 20s of January. Doing a launch event on the 24th in NYC — stay tuned! And if you’re not based in the USA, I’ll look into what I can do shipping-wise.

I am always writing things so I can figure out what I meant by things I already wrote.

As the news becomes an increasingly marginal business, stories (like the recent Lizza/Nuzzi debacle) turn into Twitter events first and media events second. The article lives primarily as a link in a post, or even screenshots in a quote-tweet, and not as a piece in a publication on a separate website.

In a way, we are more imaginative than ever with cutting edge AI, blah blah blah etc. But what I mean here is the imagining is artificially constrained. I almost find myself echoing Thiel, and his line “we were promised flying cars but got 140 characters instead.” I’d revise that to say I’d rather have social democracy than a flying car, but see the same kind of impasse.

In the graphic I’ve included, there’s also an analysis of Distracted Boyfriend as an image being involved in this process, which is why I chose it — she’s looking at him the way you’re looking at the meme.