My first viral video on TikTok was me yapping about the fragility of historical records on the internet. It randomly got 100,000 views back when I could count my followers on one hand. Someone on my FYP was talking about how crazy it was that our children would be able to see our whole digital footprints someday, and I decided to stitch them and say no, actually, the crazy thing is our kids will likely have less access to the world we grew up in than we have to the world our parents grew up in.

People used to say that when you post something online, it stays there forever, but that’s not true. Letters, documents, and even film have longer lifespans than digital files. Software gets updated, accounts get banned or deleted, and posts are taken down. Add to this the hassle of storing data and the sheer volume of stuff you’d have to not only save but organize and maintain, and you see the trouble we’re in.

On the one hand, this is a cultural tragedy. A lot of beautiful and meaningful art won’t be accessible. But it’s also a societal problem. The fragility of online artifacts and our lack of good archives should be thought of, alongside the usual suspects of “algorithms that drive polarization” and “the difficulty of content moderation,” as one of the driving forces behind the “post-truth” world people say we’re living in. Misinformation thrives when the receipts are hard to find and the past is a jumble of he-said she-said, broken links, and self-interested spin.

In a broader sense, it all contributes to an unmooring in time that is both symptom and amplifier of the disaster we have fallen into. The inability to imagine a future after the “polycrisis” which brought down the world order we grew up in is worsened by the difficulty of coherently describing the recent past, which largely took place online.1

Putting together a record of how a meme from even two years ago originated, spread, and resonated with people is almost like putting together a translation of a Sappho poem, comparing paraphrases of her poems included in essays from centuries later, scanning papyrus scrolls where moths have nibbled out words. I described some of this problem, and the way it was tackled at Know Your Meme when I worked there, in my article “How Would We Know What a Meme Is?” in the University of Amsterdam’s Critical Meme Reader series. Prior to my time at Know Your Meme, I worked for a media archaeology lab based out of Washington State University at Vancouver, where I helped archive 1990s digital writing, art, and games that lived on floppy discs and desktop machines — and the situation with that very early internet culture is similar.

My experience saving .jpegs for posterity was what led me to make that first video. I wanted people to understand that the thing we know as “history” is literally made not by the people who live it, but by the people who tell it. The past, as we may understand it now in the present or will later access it in the future, is assembled out of primary sources which persist over time: documents, archives, artifacts. On top of these records are placed interpretations and acts of imagination, which are necessary since the archive is, by definition, never complete — you can’t record everything that happened, or everyone it happened to.

The bricks from which history is built are the traces of the past we can still put in our hands, and the mortar connecting them together is empathy, theory and “the stories we tell ourselves in order to live.”2 And the brick walls of history, to extend the metaphor, become the house in which our minds and our spirits live.

Projects like the Internet Archive, Ruffle, or Know Your Meme do valuable work to give us (and future generations) some of that historical record of who we were. But it isn’t enough; these projects have little if any institutional support, and are under threat (particularly the Internet Archive, which has been targeted with lawsuits in recent years).

Memory is a contest. It is not a mechanistic psychological process of our brains, but a set of social dynamics which we negotiate together, structured by language, money, power, and technology. What has happened in the opening decades of this century is a re-ordering of those dynamics: a new set of players are involved in the game. Online publics, algorithms, and oligarchs are now the stewards of memory, replacing modernist institutions like universities, think tanks, bureaucracies, and market-driven media — which, centuries ago, replaced religion and folk traditions as the primary means by which human societies oriented themselves in history.3

In the absence of good histories of the internet (and internet history is for all intents and purposes the history of the 21st century) we will have histories that serve the interests of those who would rather deny us a future than share one with us.

In my 2023 video, I said (paraphrasing myself here):

In 2040, we might be in a situation where we know more about what happened in 1980 than about what happened in 2020. And that’s because in 1980, they wrote everything down on paper. But in 2020, almost all the conversations, the organizing, the culture was digital. And all that culture is on a privately-owned platform. So you can imagine the owner of a platform like that having an interest in history being understood a certain way. In 2040, they might want to say “here’s what really happened in the 2020 election,” and then we might not have the receipts to say “no.”

This may sound like an Orwellian doomer fantasy, but something like it has occurred many times in the past. In the United States, we have already lived through the erasure and destruction of memory — acts of targeted forgetting, not just of specific events like the burning of Tulsa in 1921, but of millions of individual lives for which the majority of traces we have left are dehumanizing receipts of sale and runaway posters. And all this continues: JD Vance is now charged with “removing improper ideology” from the Smithsonian museums.

Historian Walter Benjamin, writing in 1940 as he fled the Nazis, said:

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was’ (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger… the danger affects both the content of the tradition and its receivers… only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

Lately, I have thought a lot about the piece of Benjamin’s, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” from which those words come. It’s a brief piece, one which outlines a kind of creative and narrative mission for the historian — or for anybody seeking to remember and understand the past — deeply steeped in mysticism. Benjamin tries to articulate what led to the rise of Fascism, which he saw as marking the failure of both the liberal project and the Marxist project.

Some of my fixation on it comes from a historical analogy which, for better or worse, has been key for many Americans lately: 1930s/1940s Germany. Shortly after writing these words, Benjamin, a German Jewish intellectual, chose to die by his own hand rather than be captured by the Nazis. It seems we are currently in another, similar “moment of danger” when we must “seize hold of a memory,” but aren’t we always? Is the conception of danger as living in a moment that we may compare to other moments as if taking them in our hands and weighing them, actually a helpful analytic tool? Benjamin writes,

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight… One reason why Fascism has a chance is that in the name of progress its opponents treat it as a historical norm. The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge—unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which gives rise to it is untenable.

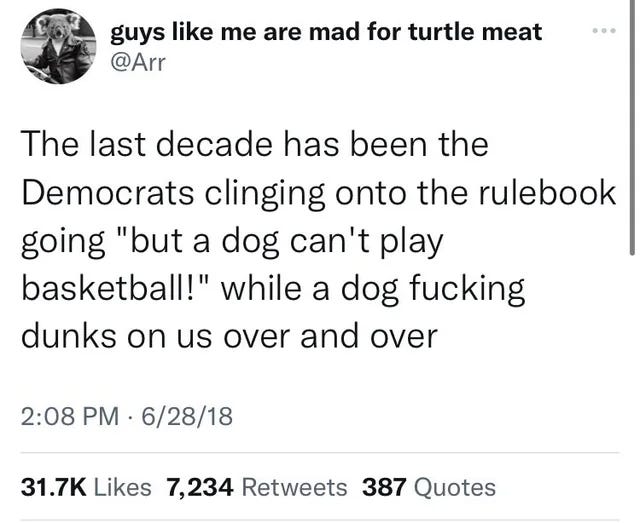

Today, we marvel that the things we’re seeing are still possible in the 21st century, saying they remind us of the barbarism of Benjamin’s time. Nearly everything Benjamin writes about the Social Democratic Party, the left/center-left bloc in Weimar Germany which failed to arrest the rise of the Nazis, could be said about the Democrats in the United States today. “(The SDP) regarded technological developments as the fall of the stream with which it thought it was moving,” Benjamin writes, and (later) he says,

Progress as pictured in the minds of Social Democrats was, first of all, the progress of mankind itself (and not just advances in men’s ability and knowledge). Secondly, it was something boundless, in keeping with the infinite perfectibility of mankind. Thirdly, progress was regarded as irresistible, something that automatically pursued a straight or spiral course… The concept of the historical progress of mankind cannot be sundered from the concept of its progression through a homogenous, empty time. A critique of the concept of such a progression must be the basis of any criticism of the concept of progress itself.

The critique of “homogenous, empty time” is at the core of Benjamin’s argument here. Progress narrative liberals see future time as a kind of terra nullius, an open frontier which we inevitably fill by becoming smarter, better, juster, and more prosperous.4 It is an open range measured in years rather than in miles, divided not by mountains and rivers but by the natural spans of our own lives, parceled out and valued not by deed, but by narratives of history and progress that rationalize, explain, and judge.

Benjamin argues this is wrong. Instead, we should view history as “time filled by the presence of the Now.” I capitalize “Now” because the footnote in the edition I’m reading argues, that in the original German, Benjamin says ‘Jetztzeit’ and indicates by the quotation marks that he does not simply mean an equivalent to Gegenwart, that is, present. He clearly is thinking of the mystical nunc stans.

The “nunc stans” is a Latin phrase meaning “standing time,” which in medieval theology is often thought of as the way God lives within time — as a kind of eternal nowness that knows no before or after. It might, perhaps, be translated into English as “timelessness.” Yesterday is as far from us as the Yalta conference, and yet it is also as near. We are like the people of the past, our suffering is like theirs, and so are our hopes. Our picture of them is made just as our own self-portrait is made: by the evidence of sensation and acts of imagination.

Earlier, I referenced Joan Didion’s The White Album, written in 1970. She was a journalist trying to make sense of a disorganized, volatile moment in America. She wrote:

We tell ourselves stories in order to live... We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

Living by the imposition of such a narrative line is the problem, according to Benjamin. There is no line. There is, instead, the “shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

The people who ran the world before the polycrisis relied on the artificial imposition of such a line. They called it the line of progress, which bounds ever-upwards on the chart and dances from crisis to crisis. The line legitimated them, explaining their position in history and their responsibilities. The past (and, nearly always, exclusively the Western past) needed its revolutions to bring democracy, but we don’t need them now. Vaccines cured the sick, diplomacy brought peace, and everything got better and better because the Enlightenment happened. Accountability in the present, or criticism of the past, was shoved aside by a faith in the future. Colonialism, slavery, exploitation of workers — these were either deferred as the detestable sins of a past era, or differed as the characteristics of “less-developed societies,” disconnected from our own. The system was not just one of material power, but one of narrative coherence. It worked because the stewards of knowledge believed they had fenced the contest of memory into a game for which they dealt all the cards and knew all the rules. Now that game is over. A dog can play basketball.

Memory and history on the internet have to work differently. The line no longer matches, stories no longer correspond. Some of this can be fixed by a more conscientious approach to the history of the present, which it is necessary to attempt.

The only force which can make the kind of world we want to live in is the tradition of protest and remembrance which has defined the cultural life of the past decade, offering the only vital counterpoint to the far right. In the United States, we see it in the way we remember 2013 and Occupy Wall Street, 2020 and Black Lives Matter, 2024 and the protests to free Palestine. These movements each reached backward, far into the past, with a sense of imagination, testimony, and empathy that has helped me and many others of my generation find ourselves within history. 1619, 1948, and 1865 are made near to us, instructive to us. But these movements also reach into the recent past, mobilizing publics through meme traditions and acts of collective remembering, mourning, and rejoicing.

As Benjamin writes,

The class struggle… is a fight for the crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual things could exist. Nevertheless, it is not in the form of the spoils which fall to the victor that the latter make their presence felt in the class struggle. They manifest themselves in this struggle as courage, humor, cunning, and fortitude. They have retroactive force and will constantly call in question every victory, past and present, of the rulers. As flowers turn toward the sun, by dint of a secret heliotropism the past strives to turn toward that sun which is rising in the sky of history.

There is a sun rising in the sky of history, as each day turns into the next. We need the tools and imagination to find it in the sky over us now, in 2025.

I follow

who recently argued that the term “polycrisis,” which he made viral in 2022, no longer describes the state of our world. Rather, as he writes, “if “Neoliberal Order Breakdown Syndrome” was one way of characterizing polycrisis back then, then the alarming thing is that things have moved on. After all, crises have two possible endings. In one, the patient recovers. In the other, the patient is dead.” The patient is now dead.Joan Didion said this. Full quote later in piece.

I work currently for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a global affairs think tank facing this problem — and so I’ve spent some time pondering the old system. Nothing I post here, or anywhere else, represents the Carnegie in any way — and what Carnegie publishes/posts does not represent my views either. But as Adam Tooze, Carnegie scholar (and previous footnote) describes, a part of the generalized crisis we’re facing (or have already been overwhelmed by) is the collapse of the “managerial ideology” which has for decades informed the approach of the researchers and policymakers who work as the primary care physicians of our ailing world. Tooze writes that “for them - for us - Trump and his ilk aren’t just ‘problems,’ they are an existential challenge, disputing the most basic ways in which we/they understand the world.” I would argue that if, as Tooze says (and this is all from Chartbook 407) Trump is “American polycrisis in one man” that a part of his “disputing the most basic ways in which ‘we/they’ understand the world” must be his movement’s essence as a creature of social media — a swamp monster spawned from a structure that is illegible to “we/they” because it is incompatible with the view of history which the “managerial ideology” requires, and difficult to approach using the methods, sources, and frameworks the “managerial ideology” trusts.

This piece in the NYRB — How to Blow Up a Planet — has been stuck in my mind lately.

This is the caliber of media literacy commentary I’ve been searching for

Thinking about this and some of your other recent posts, here’s an idea.

A GitHub for internet memory. A repository providing a way to store, classify and organize internet media as a historical record.

Form a foundation. Recruit major donors, Universities, nonprofits, charitable foundations, to fund the building of the repository.

The repository hosts individual and organization users. Small accounts are free. Large accounts, like for a university, have usage fees. Or maybe 5 free hours per month then hourly rates for additional usage. Each repository can be private or public. All of the data in public repositories goes into one main repository.

This is a nonprofit venture but the goal should be to generate sufficient revenue to be self sustaining.