kirkification: stealing a face

part one of a series on Kirk memes

Anyone who has experienced the internet should understand Kirkification was inevitable. There is no way tasteless and aggressively bizarre memes weren’t going to get made about the assassination of a major political figure. This is an internet that has been joking about 9/11 for a quarter century.

But on another level, memes always follow public trauma. Humor is a coping mechanism and Kirk’s death was a horror played out across millions of handheld devices. The background hum of contemporary American life — that sense of chaos around the corner, the imminent puncture of a false normality — rose to the front of your awareness and you had to sit and listen to it. People needed to confront that, talk about it, process it, and so they made memes.

And nobody else was helping them do it. Pundits, journalists, and normie politicians declared political violence is “not who we are” and praised Kirk as a champion of open debate (laughably untrue on both counts). Meanwhile, the government declared they would do McCarthyism again and that Kirk was like their dad but also their son.

In the absence of coherence and clarity from the people traditionally tasked with framing the narratives of public life, people turned to one another — to social media. Kirkification is the result of this larger process of people searching desperately for a language to match the craziness they see, feel, and experience. Like many political memes, it is simultaneously mass protest and petty complaint — but it is also a search for new forms to express, explain, and (perhaps) change politics today.

In this series of posts (of which this is the first) I’d like to explore a few of the Kirk memes and how they may gesture towards new forms, offering a reading grounded in their historical and meme-cultural context. There are many types of Kirk memes and many ways of looking at them, so my accounting will inevitably fall short.

Kirkification face-swapping

The first thing to keep in mind about the Kirk memes is they tend to align with previously-existing meme traditions — they do not emerge from nothing. They move along well-worn paths and genres, responding to other trends and meme forms that are on social media scrolls at the same time.

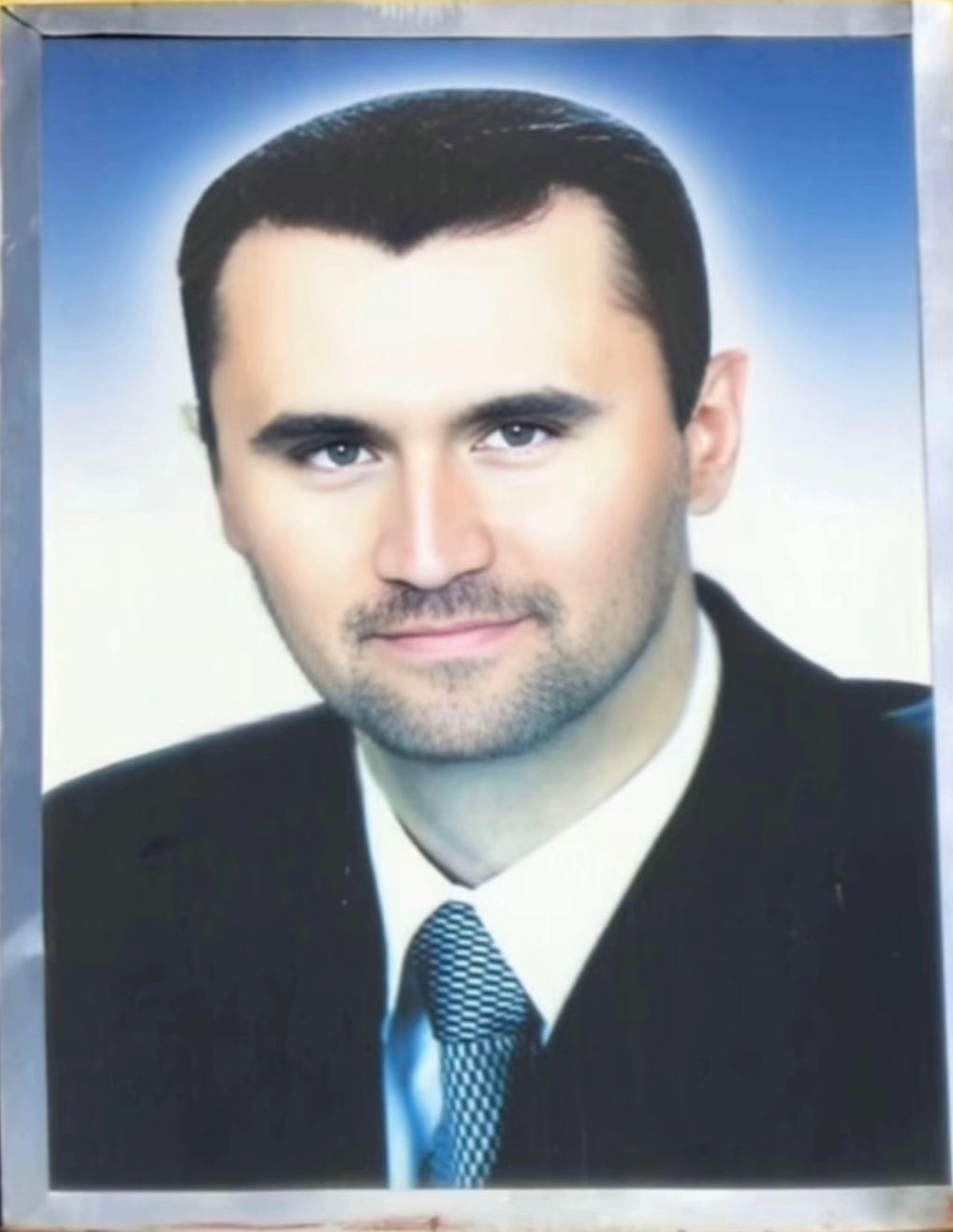

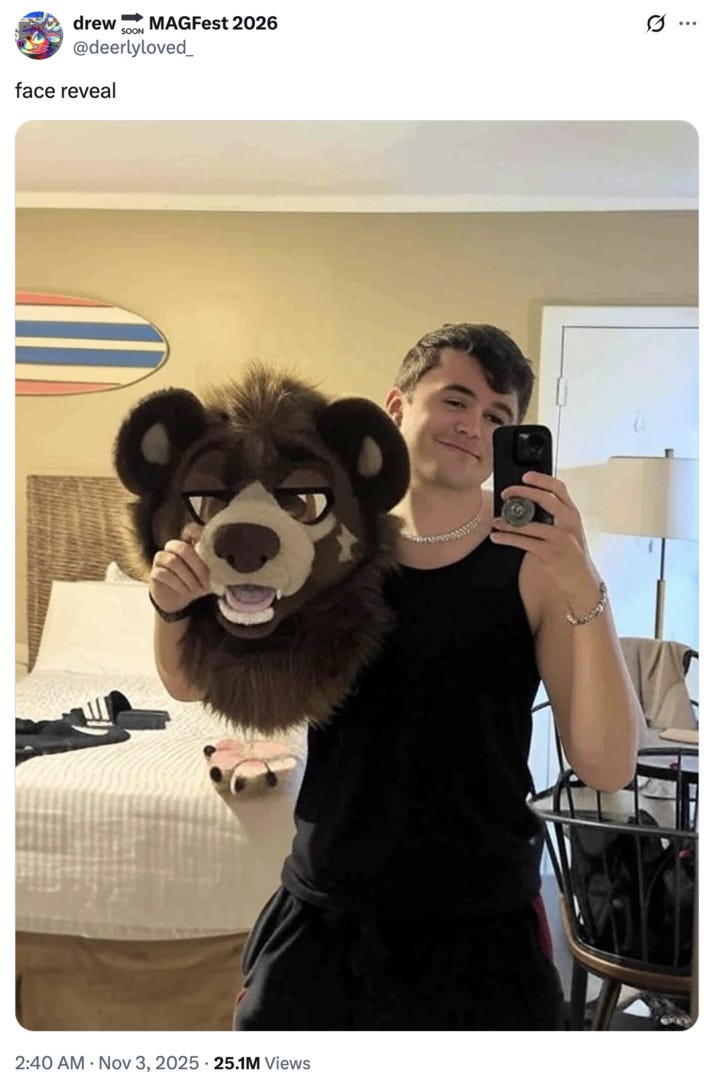

“Kirkification” itself is the editing of Kirk into famous photos of celebrities, or even just videos of everyday people taken with front-facing cameras (these are my favorites). It’s just a face swapping trend. There have been tons of face swapping meme trends over the years because it was one of the first funny things people figured out how to do with image-editing software, and we’ve likely all seen them before. Contemporary face-swap memes may use AI to streamline the process or do it faster, but you really don’t need AI for this. It will always be funny to put Charlie Kirk’s face onto Clairo’s body, in the same way it was funny in 2009 for somebody to do this:

Often, these face swapping memes choose body-face pairs that bend gender and race, with the Kirkification memes being no exception. The majority of Kirkification memes I’ve seen put his face on a woman’s body, which feels charged considering Kirk’s public life was defined by constantly asking the question “what is a woman?”

A major antecedent to Kirkification are the memes surrounding the face of Vice President JD Vance earlier in 2025 — or, more accurately, the chubby-cheeked memefied version of Vance’s face. Face-swapping was only part of the broader memefication of Vance, just as it is with Kirk, but the gesture and political valence are similar.

With both the Vance memes and Kirkification, the internet declared sovereignty over a person’s image. The faces of both men were stolen from those who would prefer to control the image-making around them.1 This should be seen as a political move against the administration on the messaging terrain that it cares about most.

For MAGA, power flows from images and it congeals through posting. The movement’s ability to stage the landscape in which foes and friends alike encounter reality is, alongside corruption-money from rich people, the core of its power. The primary activity of this administration is meticulously posing, pitching, and posting itself — and it is largely constituted as a coalition of posters. Claiming Kirk’s image — turning him into “2020s Harambe,” as Ryan Broderick quipped recently — is a move by posters against posters.

Kirkification as spectacle-seizure

Most people, particularly very young people, experience political life first and foremost through posts that help determine how they feel about themselves. Bills come once a month, but the scroll comes every day, for hours. The podcaster makes you feel smart, valuable, and safe. The culture war gives you a group to stand with at a time when social life is endlessly confusing and fragmented. Your vote doesn’t matter much, but your posting (or support of a political creator, like Kirk or Fuentes) can influence policy at the federal level, changing what people talk about in Washington and how they see problems.

The social media conversation is perhaps the only input into contemporary political life that everyday people feel they have some kind of involvement in or control over — everything else is bought or bureaucratized. And in the lifetimes of most of us under thirty, the system has only ever delivered images. It’s all we know how to expect.

So when I think of a seventeen-year-old Kirkifying themselves, in most cases I don’t think they’re primarily doing so because they are a progressive who has decided, based on their policy preferences, that Charlie Kirk was not a person they respect. Rather, they’re someone trying to reclaim a form of collective agency. The killing of Kirk, the graphic footage everywhere, the cynical political spin that flooded our digital havens and dominated conversations with people all around us, was something that happened to us which was scary, distressing, and wrong — but Kirkification is something we made happen.

People use politics to make themselves feel good. They also use it to make sense of the world. It is about emotional regulation and explanation as much as it is about outcomes. Kirkifying yourself and joining the trend offers a feeling of agency, the ability to contribute to the story rather than have it wedged into your skull by people who want to manipulate you. Similarly, Kirkifying a famous picture offers you the chance to take control of this story, or any story, and tell it your way rather than have it told to you in their way. It’s about what people stand for, what they believe should happen in the world, but it’s also not — it’s about vibes.

Kirk and Luigi

The post-mortem mocking of Kirk evolved into a political stance for many people, less about the event itself and more about the stories powerful groups wanted to sell us after the fact. In this way, a clear influence on Kirkification (and Kirk memes in general) are the memes around Luigi Mangione.

A man the media wanted people to see as a villain and a harbinger of something bad was instead memed into a folk hero. Kirkification is a weird mirror of that: a man the media wanted us to see as a folk hero was memed into a joke.

Luigi became a hero less because he was particularly wonderful (by all accounts, Luigi is a chud who (allegedly) murdered someone) but because he was A) kind of hot in an Italian way, and B) making Luigi a hero was a way to refuse to read the story as they wanted you to read it. People took control of his image, which had first been presented as a mugshot, and transformed it into a thirst trap. Performing that alternative reading of the news is a political signal, a refusal to accept a framing of the world that leaves us and our lived reality out of the picture.

A counter-argument I’ve often seen to my content is “it’s not that deep bro.” A lot of people think kids just say 6-7 because other kids are saying it, that people just Kirkify themselves because Kirkification is a trend and we’re sheeple. For many posters, this may be the case. But a trend starts because it incites something in people. It’s funny because it says something, projects something that makes us see reality a little differently, perhaps a little more productively. Memes are produced by an audience in search of new forms. The memes themselves are not the final phase, but a reaching.

The new forms must involve offering citizens, fans, and audiences the chance to make stuff happen — to address them not as consumers of a message, but as co-producers. All this is to say that the first national Democrat politician to Kirkify themselves on main will win the 2028 primary. Gavin, we await your posts.

JD Vance may embrace the Vance memes, posting as if he plays along with the joke, but it’s clear in the strained tone and overall desperation to be liked that this is cope.