My finest hour as an internet culture commentator — which few people saw — may have been this video from March 2025, commenting on an alleged “meme drought" or “great meme depression” which people were talking about:

If we’re in a meme drought right now, it’s because you need to be looking beyond American and English language brainrot. There are dynamic, interesting memes happening all around the world right now. Like Bombardiro Crocodilo… the biggest memes of this summer probably already exist, you just don’t know about them yet.

No prediction of mine has ever proven as true. In the months since March, Italian brainrot like Bombardiro Crocodilo — still photos of AI-generated chimera critters accompanied by an Italian-language voice track — have exploded across the web. A lore has grown up around them. Some Italian brainrot memes have even fused with the John Pork lore. I can’t say that I was the first there, but I do believe I was among the first fifteen percent of people to learn about Tralalero Tralala.

In this post, I want to look at two dimensions of Italian brainrot: first, as something “Italian” (to the eyes of non-Italians most of all) and second, as a meme tradition of obviously AI-generated images, telling us something about this technology’s entrance into visual culture.

In Roland Barthes’ brief essay “Rhetoric of the Image,” which describes the methodology Barthes uses in so many other places (such as the “wrestling” chapter of Mythologies, which

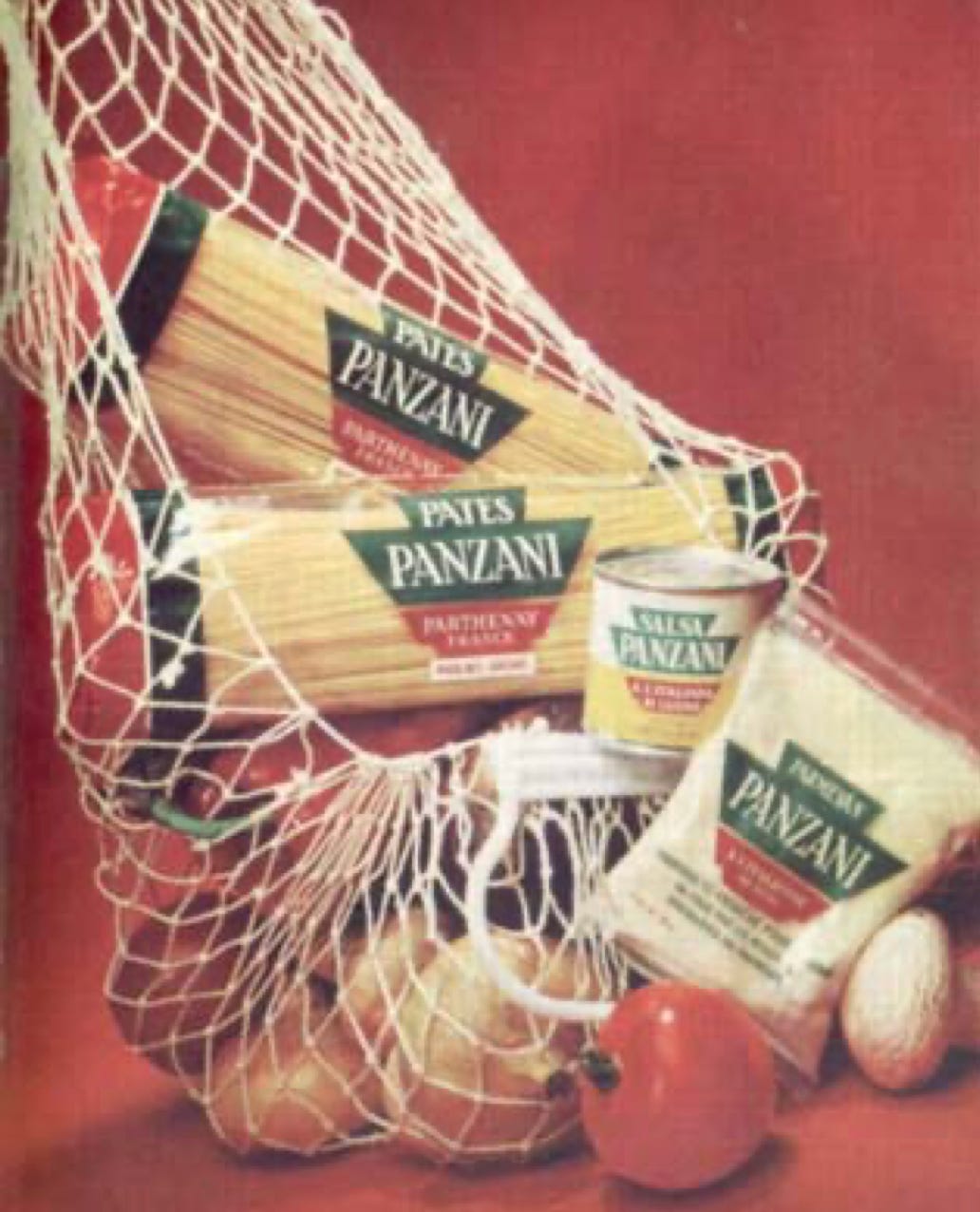

lately used to brilliantly describe the Iran situation) our boy analyzes a print advertisement for a pasta brand which was sold in French grocery stores in the 1950s. Here it is:Barthes treats images as if they are words, applying concepts from de Saussure’s linguistics. In Barthes’ visual rhetoric, color, size, and shape stand in for abstract concepts in the same way that volume, pronunciation, and intonation do in spoken rhetoric. The sign is seamlessly joined to its signified by repeated, conventional usage. A logo becomes a product just as the letters of “duck,” while having little to do with the real bird itself (which has other names in other languages) become the creature. Sign and signified meld together.

But as you know, there are things in our world which words can’t express. Just saying you “love” does not really encompass your whole experience. But the other side of the equation is also true: there are things which words express that don’t actually exist in our world, things that are not concrete but which signs make real and present.

Barthes sees the pasta ad as a sign of particular signifieds (abundance, the feeling of just returning from the market, visual references to the sill life painting tradition). But also, “..its signified is Italy, or, rather, Italianicity.” The image mobilizes a knowledge, but

the knowledge mobilized by the sign is already more particular — it is a knowledge properly “French” (Italians would hardly perceive the connotation of the last name, nor (probably) the Italianicity of the tomato and pepper) founded on a knowledge of certain touristic stereotypes.

“Italianicity,” as a construct understood by French people (or any non-Italian group) is not real. Barthes marks this unreality by spelling it italianicité, distinct from the more conventional italianité, a difference I’ve tried to translate into English by saying “Italianicity” instead of “Italianness,” which is real.

But this “Italianicity” does exist as a force in the world, one which firms like Panzani profit from and which people, whether Italian or not, must reckon with. It is also “mobilizable” by particular images and utterances. In other essays, Barthes extends this chain of reasoning: ideas like “love” may be placed in the same category as “Italianicity.” They are complexes of signs, discourses. My favorite Barthes book, A Lover’s Discourse, is an account of this, going sign-by-sign to figure out what makes the discourse of romance in the 18th-20th centuries in Europe.

“Discourse” here steps into a definition altogether separate from how we generally use it on the internet. For Roland, it is the word for a family of signs, often contrasting, which take on various historical forms (archives, broadcasts, conversations) but seem to have a weird independence, weaving between speakers, living somewhere between content and context.1

And so, I think Italian Brainrot participates in the discourse of “Italianicity” but not “Italianness,” just as Roland’s pasta ad does. After my video analyzing the trend, several Italians slid into my DMs and comments insisting Italian Brainrot wasn’t even that big in Italy — that it was more popular in Latin America. While the origins of the meme do appear to be Italian — the first audio, paired with the earliest version of Tralalero Tralala, emerges from a different Italian meme tradition which depicted the Rock receiving stories from a friend called “Burger,” or so my informants reported — its subsequent growth and spread is transnational.2

Read by an AI voice, likely translated from another language into Italian by another AI, and translated back for the viewer in subtitles via yet another AI, these memes don’t really require any knowledge of Italy beyond the kind of “touristic stereotype,” the Italianicity. After all, an AI camel morphed with a refrigerator is no more Italian than it is any other nationality — and the easy incorporation of decidedly non-Italian Tung Tung Tung Sahur into the lore speaks to the non-specificity of it all.

And so I think the point is “foreigness” rather than “Italianness.” The reason why it is “Italianicity” is because that discourse is broadly familiar around the world (“Bulgarian brainrot” wouldn’t land the same way) and not particularly charged (“Chinese brainrot” like Donghua Jinlong or Jiafei, tends to carry a political valence, readable as ‘cultural appropriation’ or as ‘critique,’ while “Italianicity” just doesn’t fall into those same associations).

The use of Italian language here is like the use of impact font in an Advice Animal, purely conventional. But why is it so attractive for people to post a meme in a language they don’t know? Part of it is certainly due to the eternal impulse within meme traditions towards incomprehensibility, randomness, and oddity. Another piece of it is a desire to connect across cultures, to be cosmopolitan. People have always thought stuff from other places is cool, and foreign content is more accessible now online than it has ever been. My videos on international brainrots have done numbers specifically because human curiosity about one another is such a strong and widely-held feeling.

And yet, in Italian brainrot — unlike others I have studied, such as Lakaka, al-Rahma, and Potaxie lore — there is an odd severance of the sign from any signified, which I think is part of the meme’s point. The Panzani ad invokes Italianicity to sell pasta. Brr Brr Patapim does it to be “different.”

The severance of the sign from any signified is an impact of AI, and Italian Brainrot exemplifies this look and feeling. Everything AI-generated seems to come from a country to which no one has ever been, where the writing is in a language nobody can read, and signs float without reference to any signified.

LLMs use language fluently, but only engage with it on the level of the sign. They are pure langue, and not parole. An LLM does not choose words, it regurgitates them. An AI image generator has access to “Italianicity,” but not “Italianness.”

Rather than matching experience to sign, as we do when speaking or writing, AI matches a sign to another sign. In the latent space where models “think” (you have to put that in scare quotes) sign are woven together across several dimensions. “Blue” exists at the intersection of several vectors. A notch up in one direction you find “blur,” just one letter away. Another notch up, in another direction, you find “For the Roses,” the next entry in Joni Mitchell’s discography. Another way, you discover “Red,” another primary color, “Cerulean,” a synonym, and so on. These notches are not tied to particular felt experiences, because the AI has none. A difference of spelling (as in “blur”) is the same to the AI as a difference in quality (as in “red,”) and while it does recognize color and orthography as separate systems of differentiation within human communication, that recognition is merely because that has been labelled for the computer. There is no underlying ontology here, which is why AI systems hallucinate: they can’t lie, but they can’t tell the truth either.

An AI does not produce language, it extends language — they fill in a gap, predict the next word. Their “minds” are collections of scraped data latticed over by frameworks for organizing and reorganizing that data. They are the product of language itself rendered animate. Codes replicating with no need for a mouth or fingers to articulate them. When you say thank you to ChatGPT, you are not talking to an agent, but to a discourse.

Jacques Derrida writes, in his famous lecture on “Différance,"“:

… (de Saussure’s semiotics) implies that the subject… is inscribed in language, is a "function" of language, becomes a speaking subject only by making its speech conform - even in so-called "creation," or in so-called "transgression" - to the system of the rules of language as a system of differences…”

Our consciousness is made possible by the system of différance, of signs and signifieds. For Derrida, language precedes us and succeeds us, we are a “function” of it, and our selves are only legible and real by the discourses in which we are placed, our selves are made by them the way that sweat is produced by a body in motion.

You might not think this is true of human selves, but it is almost certainly true of artificial intelligence. Italian brainrot, as a class of meme, interrogates what happens when we attempt to prod the discourse into producing signs that are as far as possible from any reasonable signified. AI-generated memes take this newfound ability to goad our language into speaking without us and use it to produce the most profoundly alien things possible, so we may test how they feel and look.

Part two in the next few days, as a paid post.

I am, maybe, giving a Foucauldian definition of discourse more than a Barthes definition here — but I have the sense the two are near enough, and depart from the same base.

One could argue that the fusion of “Burger” and Dwayne the Rock Johnson points to a certain “Americanicity,” which has been key to many memes in English.