There’s a strain of thinking which says we must take the phones away from the children because they come to college and can’t read “great books.” The most prominent voice calling for this kind of thing is Jonathan Haidt, with his book The Anxious Generation.

It’s not entirely incorrect, but it misses the mark in a way that, like Pete Hegseth missing his target when he threw that ax on Fox News a few years ago, could really hurt someone. This discourse centers around a “studies say” rhetoric that cloaks in science what is a fundamentally emotional point: “we should go back to how it was when I was a kid.”

I never had that pre-digital childhood, and so people of my age and temperament are excluded from this vision of what society “should be.” The culture I grew up with, cover, and analyze is dismissed.

I also know the kids actually have critical thinking, media literacy, and an appreciation for language and stories, at least as much as their parents did. It’s just that they appreciate the way these things live on the internet. For some reason, folks get bothered by that. Otherwise very smart and respectable people turn their brains off the minute they hear “skibidi toilet.” It’s annoying to see that reflex.

And it’s nothing new. Plato’s Socrates, in Phaedrus, argues that writing is bad because it makes people forgetful. The new communications technology lacks the grounding and trustworthiness of the spoken word, Socrates says. It will be used by bad people for bad aims, it will corrupt the youth. Every time a new communications technology comes along, people see the world they grew up with vanishing, and worry about the state of the one they must leave their children.

However, in our case, the issue is not so much the technology itself but the economic and political structure that technology serves. It was a choice to make the internet into a confederation of extractive cloud fiefs. It was a choice to make the screens into dank serotonin cages for a generation unmoored by a pandemic, economic disintegration, and political upheaval. The problem is not your students who have fried their attention spans by overindulging in today’s most available vice, but a society outside the classroom that has turned rancid.

The idea that a phone ban in schools would help the children more than fairly taxing billionaires is dumb. In a previous post, I talked about how some have tied the rise of big tech to the financialization of the economy at the end of the 20th century. We live under slop capitalism, but there was nothing inevitable about any of it, nor is it a fate to which we must be doomed.

Media theories like Neil Postman’s can turn into a means of side-stepping a deeper critique of inequality and bad policy. We can never save the world we grew up in, but we can contest and make better the world order we’re being shoved into. That’s what it means to be a political subject and a citizen, at any point in history. It means to inhabit agency and make vivid those values you care for, like critical thinking, diversity, open-mindedness, artistic expression, and empathy. Those values lead me to venerate 2020s brainrot for the same reasons I venerate 1920s modernism.

As a teenager, I fell in love with William Faulkner around the same time I fell in love with surreal memes, and for many of the same reasons. I got a lot ego-wise out of precociously reading Faulkner, and I also got a lot out of feeling “in the know,” and understanding memes that others weren’t online enough to get. But in both cases, I stuck around because I found the art to be beautiful and troubling, because I was fascinated by the glimpses of other lives, times, and places it offered me, and because I saw the value of both memes and Faulkner as companions to take with me in my brain or backpack as I went to the places I had to be. I had great teachers who encouraged me in this, some of whom maybe still receive and read this newsletter!1

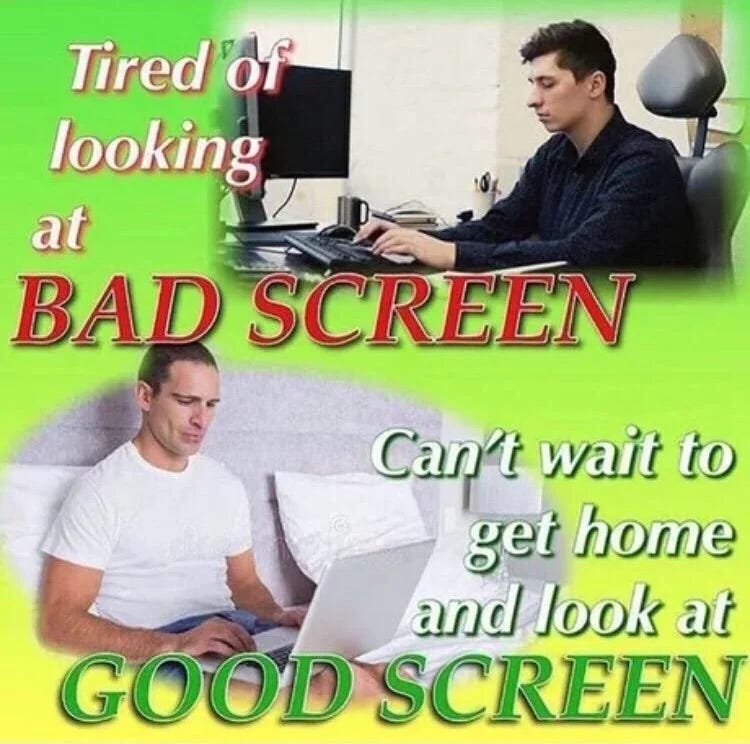

Later on in college, I learned to read more analytically: to scan Faulkner for clues about the way history made the America I grew up in, for the ways he recorded the specific pathologies of racism and sexism in his era (I remember a line in Absalom, Absalom! Quentin’s father talking to him, was a lightbulb moment for me — “Years ago we in the South made our women into ladies. Then the War came and made the ladies into ghosts.”) Memes have inspired similar lightbulb moments in me, and are just as informative about our culture. Memes are social commentary, reflections of power dynamics, and the points where tensions become visible. In Chris Hayes’ great new book, The Sirens’ Call, he describes in text a specific meme he saw and as I read it, I remembered that I knew and loved that meme too. I embarked on a search through my folders. It was this one:

The meme seems to have originated six years ago from the /r/antiwork subreddit, which is a community organizing space for people protesting against manipulative bosses, unfair employment practices, and the gigification of labor. You see here a clear political critique, but more interestingly an illustration of a particular lifeworld spent bouncing from screen to screen. It ties the intimate and personal into the political in a way that people all across social media do, but you rarely see in actual political writing. I’d challenge anyone to cite a moment in contemporary fiction that does better at depicting that feeling and vibe.

The other thing about memes is how weird they get, and that’s what experimental fiction is all about. In Absalom, Absalom! there’s a sentence which is over 2,000 words long. In As I Lay Dying, there’s a chapter that just goes “My mother is a fish” and that’s the whole chapter. The entire Southern Gothic thing is so insanely camp at the same time as it’s dark and brooding. This kind of weirdness, ambition, and willingness to push the limits of form are there in memes too. There’s a take-no-prisoners attitude that doesn’t care what anybody thinks, it’ll just do what’s true and best — that’s the spirit of art, isn’t it? And if you don’t see that in internet culture too, you’re not paying attention.

It can be hard to see the cultural value of memes because they don’t have authors in a traditional sense, and we’re so used to fixating on authors. A while back,

wrote an essay arguing There Has Been a Drought of Cultural Greatness For Most of the 21st Century So Far. He mentioned me in it, so I am mentioning him back here, with a friendly rebuttal. He argues that throughout human history, there have been “two kinds of people in the world: those who have been content with comfort and those who strove for greatness.” The second kind of people are the ones who make art, and the issue with social media is that it muffles them, placing us in a “gossip trap” that stifles innovation, that leads us to stay in our lanes, conform, and not innovate.

But that’s not how art gets made. A Romantic view of the individual artistic genius, crafting castles in the sky, is a relatively recent innovation — two hundred years old at best — and it isn’t factual. You look at the biography of any great artist, and you see a massive supporting cast. You see spouses, secretaries, editors, agents, interlocutors, and educators who built them. You wouldn’t have Faulkner without Estelle, Phil Stone, and Ben Wasson. Rembrandt had a workshop, the Impressionists saw themselves as a group. In a broader sense, all this art needed a tradition to draw from and an audience to meet it. One of my favorite Faulkner quotes is when they asked him about his place in literary history:

If I had not existed, someone else would have written me, Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, all of us. Proof of that is that there are about three candidates for the authorship of Shakespeare's plays. But what is important is Hamlet and A Midsummer Night's Dream, not who wrote them, but that somebody did. The artist is of no importance.

But people don’t like seeing it this way. You look at a lot of what gets published about books nowadays in literary magazines or academic journals and it’s often profiles of “such and such” person, always identified by last name. It is as much biography as it is criticism. Instead of writing about the words, people write about the people who wrote the words. The author is the protagonist here, and the meta-history of 20th century English-language literature is the story of brilliant individuals pursuing their creative visions and triumphing through education and grit over whatever historical forces (capitalism, ignorance, prejudice, etc.) stood in their way. It is an essentially mythic narrative, and a useful one too—because isn’t that how a lot of people, particularly those who love reading books, experienced their lives in the late twentieth century in the United States?

Actual art is relegated to the status of a prop or fetish object that serves to incarnate the myth of the author. People talk about “Woolf” rather than Mrs. Dalloway, “Plath” rather than Ariel. Janet Malcolm’s book The Silent Woman, a biography of Sylvia Plath’s biographers, is a great deconstruction of this myth and appreciation of its beauty and historical embedding.

The force of the myth is part of what draws many people to become English majors or write novels, but a myth is best taken in moderation. It empowers, but it can also defuse art by making it a brand, and slyly aligning aesthetic experiences that would otherwise be subversive or mindset-expanding with the cultural mainstream of individualism, elitist credentialism, and — ultimately — slop. People come to love authors and not books, accolades and not achievement, images of “the good” or “the true” which are more absolving and easier to hold than the things themselves.

Meme traditions offer many of the same things as literature but with a different set of myths attached. They have their own neuroses and they lead to their own kinds of darkness. But they’re also beautiful.

Which is why I think we shouldn’t vilify the phone. Instead, we should learn to live more effectively with it, and understand the culture that curdles and blooms behind its glass eye. The point is not to find “greatness” as some trans-historical property, but to find what we need to know and be right now.

Emma Bovary, rotting away in Yonville, would have loved Instagram if she were a young woman in 2025. And it would have killed her in the same way romantic fiction killed her in 1857. What back then would be a realist novel, depicting an anxiety or identity-experience in narrative form, would today be a social media drama. What back then would be poetry, contorting language to the edges of what it can grasp, would today be surreal brainrot pushing the post to the edges of what it can express. And it is just as fraught, fearsome, fascinating, and fun.

Thank you so much for everything.

Really love this bit: "People come to love authors and not books, accolades and not achievement, images of 'the good' or 'the true' which are more absolving and easier to hold than the things themselves."

no, the medium really is part of the problem. A mediated experience is by definition at a remote order from 1st order experience. Crucially different from looking down at your feet, or watching your fingers typing.

I realize that it's unlikely that you can be talked out of your position. Twelve months without access to television computer screen, or phone would almost certainly change your perspective. Quitting all screens including the pre-digi medium of television is crucial, though. The attention economy era began before the social media era. In some sense, a/v phone content is merely television with a faster payoff and optional interactive features.

I agree with you about the Star System for writers. And people who confine their literacy to reading reviews, instead of actual books. But don't be hasty about consigning authors to subordinate importance to "the text." Authors who are good deserve the credit for doing a good job of using their own voice. To avoid Star Syndrome, go to the library and pick up short story anthologies. There are sleepers to be found there.