don't log off

online hope in the time of monsters

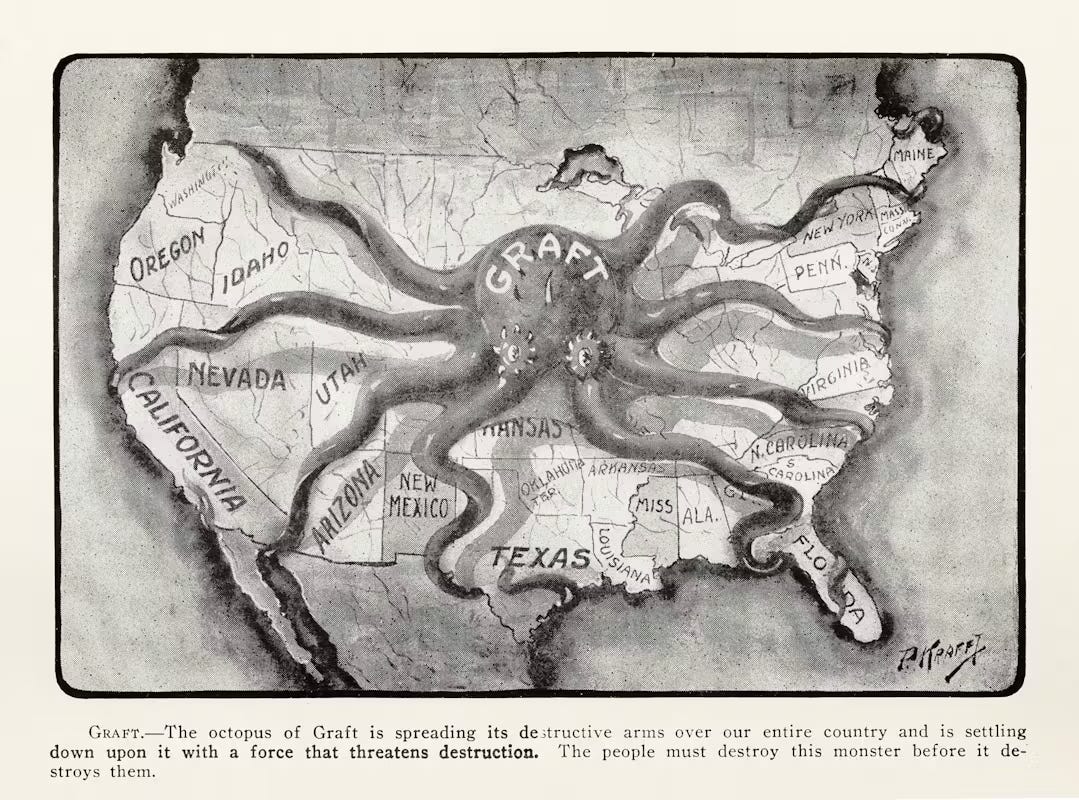

Chat, we are cooked. As Antonio Gramsci is said to have put it in 1930 and Ezra Klein, quoting Gramsci in the New York Times last week put it, “now is the time of monsters.”1 That’s the unavoidable context for anyone posting now — and to the extent the internet is real life, this is the cloud which shadows all we do.

Tomorrow, we will see the inauguration of an authoritarian regime in the United States that is deeply enmeshed with the tech platforms. Yesterday we saw a ban of TikTok that has been reversed at the price of that platform collaborating with the same regime. A new and probably worse era is beginning.

While fire eats Los Angeles, rumors say the promised raids on immigrant communities are imminent, and the President-elect has octupled his personal fortune through a profoundly sketchy memecoin. The highest court has already decided he is above the law, and the world already overshot the 1.5 degrees celsius warming threshold in 2024.

The institutions did not hold. The only thing left is us. Even if you’re not American, the story everywhere, particularly in Europe, is similar.

Of course, it does little good to rehearse all the ways in which we are cooked. You already know.

Instead, let me share two facts about social media which give me some limited hope:

#1

Looking at the history of platforms, the only constant is radical change. TikTok has only been well known for about four and a half years. If Facebook were a person, it wouldn’t be allowed to order alcohol at a bar in the United States. Internet culture has gone through several distinct eras in a span of time that is about as long as a dog’s average life. The entire game gets rewritten every five years, if not more frequently. So it is reasonable to expect that the way things are now on social media is not the way they will stay, regardless of how much very rich people want them to stay that way.

#2

The most powerful group on the internet is everyday people. Contrary to the media and academic narratives we frequently see, which emphasize the agency of companies, regulators, and algorithms, the internet is ultimately user-generated. The content people are looking at, and the products they buy, come from other people just like them.

The actions of a Zuckerberg or a Lina Khan are easier to study because they happen within the frame of organizations that, at their core, are familiar twentieth-century structures: the megacorporation and the government regulatory agency. But the real force that runs the internet is a digital public, a very twenty-first-century structure which we don’t yet have the vocabulary to describe adequately or the political structure to mobilize effectively.

The case for a limited optimism

My limited optimism comes from the conviction that we can develop the vocabulary and the political structure necessary to shift power to a digital public. The internet has radically changed several times before, so why can’t it change in a democratic direction rather than an authoritarian one? Nothing is inevitable, especially online. People thought AOL and MySpace would last forever.

This is the only option left. Open, online-based democracy is the sole humane and rational response to the current situation. The liberal institutional response failed in this past election, proving itself more radical and uncompromising in temperament than any democratic socialist.

Now, I don’t believe the people will rise as an unstoppable tide and sweep away the old regime. I understand that a digital public acts along channels and frameworks laid down by authority. But the other side of the equation also holds true: authority operates according to how digital publics flow. And this is where the shape of a new settlement starts to be discernible.

Memes and mass power

One way to read memes is as moments when this public assembles and flexes its power. Making something go viral is less a testament to an algorithm’s power than an audience’s. Take as a recent example the Vexbolts mass unfollowing, which is profoundly dumb but also meaningful.

Vexbolts is a moderately famous streamer who came up with the “let him cook!” catchphrase. In late December, there was a meme about “leaving Vexbolts in 2024” and performing a mass unfollowing of him right as the year changed. The joke was funny because there was no reason to leave Vexbolts in 2024 — he was not getting cancelled, he was not remarkable for any reason, and most people didn’t even know who he was. But in order to get the chance to unfollow Vexbolts, at least four million people started following him for the first time.

The trend became large enough that major brands and MrBeast got involved. The internet system adjusted to match the coordinated behavior of all these users who, for whatever reason, decided to spend a few moments of their lives helping make a number on Vexbolts’ profile go up really fast and then go down even faster. Most of them unfollowed Vexbolts, in a coordinated strike at the toll of midnight.

This meme fits into a broader trend of memes that center around posters acting as a mass to demonstrate power over attention — to make an obscure glycine manufacturer called Donghua Jinlong famous, to redistribute money from the Creator Fund to people in medical debt, to purposefully read images of a CEO shooter as thirst traps.

The algorithm is ours, not theirs. That seems to be the message of such memes, and I would argue it’s their attraction as well. One of my favorite papers argues we should reinterpret MrBeast’s fandom not as an audience seduced and held hostage by his hooks and viral video secrets, but as a constituency which sees MrBeast as their representative, and views their attention as a donation to the charity he does on their behalf.

MrBeast, by this reading, isn’t the most popular YouTuber because he studied the algorithm and created calculated, targeted content that would perform well (although he certainly is great at the algorithm). Instead, MrBeast is the most popular YouTuber because he turns himself into an effective vessel for a digital public to act through — or, at the very least, to fantasize through. The deal implicit in his videos is that your watching turns into money, which MrBeast then gives to others in need, or if you’re lucky enough, he finds you in some Walmart aisle next to the Feastables chocolate bar display and gives you a suitcase full of hundred dollar bills.

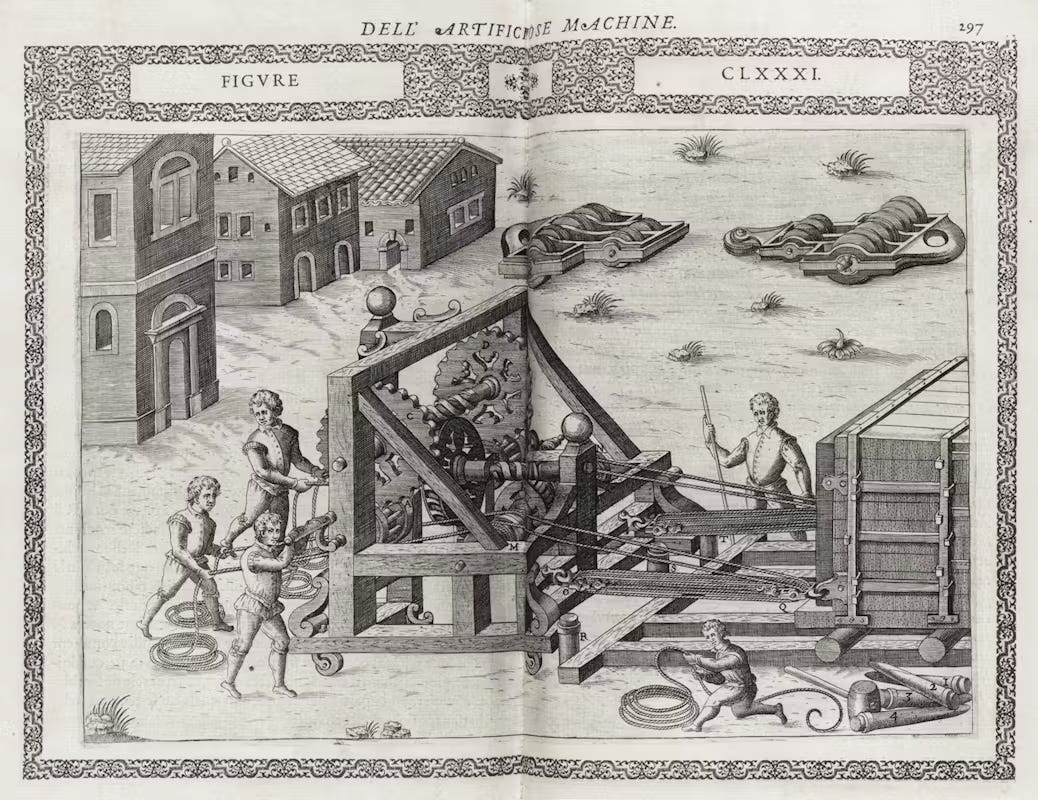

We see this in other parasocial relationships. Audiences see creators as representatives of their values, their views, and themselves. Online parasociality, as opposed to regular fame, is an instrumental relationship where the audience has the most power. Fan labor and attention are given in return not just for whatever the content might be, but for representation and validation. The beloved microcelebrity becomes an extension of a collective self, doing, being and saying things on our behalf. Creators are puppets, and the numbers generated by users acting together are the hand inside of them. Or, for a more precise metaphor — creators are marionettes, the algorithm is the strings, and the puppeteer is people.

Platforms and the posts on them belong to the people. The forces have kept or will keep us from exercising full, direct control — whether coercion, censorship, AI agents, the difficulty of mobilizing at scale, fragmentation into separate niches — are obstacles to be surmounted rather than walls that can always block forward progress.

Stay logged on

Which is why I think you should remain engaged online to the extent you can. If you leave TikTok, Meta, or X, leave it to go someplace else online and work there to make change.

Pay for a Patreon or Substack. Become a mod or admin for a community you care about. Seek out and support the posts you believe in. Flag bad content. Boost good content for the algo. Participate in the comments section when you usually wouldn’t. Troll the adversarial ecosystem of rightwing critics and influencers. If, like me, you have any kind of platform (however small) make yourself an instrument of the people who follow you, and measure your success by how well your posts represent their values rather than the fake numbers these platforms spit back at you.

These tasks of digital citizenship are profoundly important. Whatever the political structure for democratically mobilizing the power of digital publics may be, it will involve roles like these. So what I’m trying to do is practice them as much as I can. I wish to be a functional part of a broader network, which will require millions of little knots like you and me to hold it together.

The question to ask is, what are the responsibilities and opportunities that arise from this moment, and where can we direct our attention, dollars, and platforms to most effectively protect our people and planet?

Assorted notes: I did a piece on the TikTok ban for the BBC, was on ’s podcast Social Sleuth here on Substack, and have been Posting through the ban over on the TikTok itself. I also am uploading my TikTok archive to YouTube, where you can see all my posts about why Peter Thiel is mid and view my comprehensive upcoming Skibidi Toilet analysis video essay that will drop, 100% certain, before the end of the month. Most of the images used in this post came from the Public Domain Image Archive, a cool new resource from the Public Domain Review!

One of the most famous English translators of Gramsci is Joseph Buttigieg, father of Pete Buttigieg. Renowned Marxist economist Donald Harris is also the father of Kamala Harris. Rather strange that if I had a nickel for every prominent moderate Democratic politician with a well-regarded Marxist scholar parent, I would have two nickels.

it is also interesting how humor (memes, for example) drives people to action. we often do things just for the hell of it. which makes me think about how we can combine serious, well-thought out movements with this humorous element. especially because doing something for a joke takes less mental energy for the people, meanwhile approaching a topic with grave seriousness often makes people depressed or apathetic. another driving force is obviously anger or hatred which is still linked to humor since it is often spread through jokes and memes

I am looking for any bits and pieces of hope I can find in the face of this current madness in the US. This has provided me with a bit of hope. Thank you.