Comparing ChatGPT and McDonald's

slop capitalism, revisited

I was in rural Virginia looking for a place to eat and the closest thing, twenty minutes away by driving, was a gas station selling fried chicken. Attached to the place’s entry in Google Maps were a series of reviews left by people who care enough to rate gas station fried chicken. The business had replied to each of these reviews politely and succinctly, thanking the positive ones and making diplomatic excuses or apologies to the negative ones.

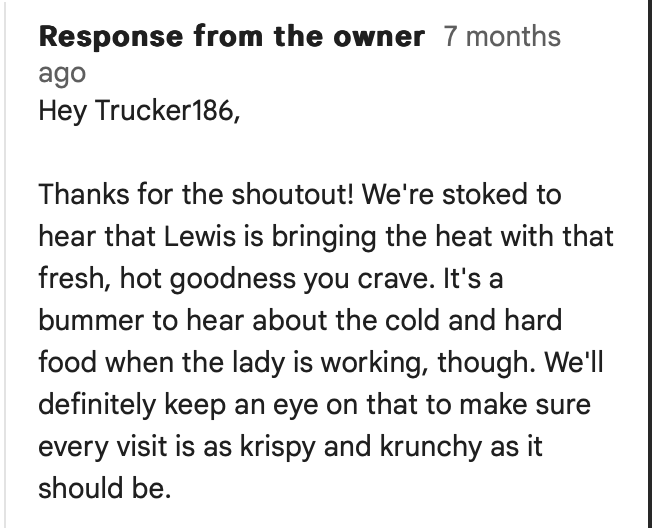

I instantly recognized the writing style of ChatGPT:

There’s no way to know for sure it’s ChatGPT, but I don’t see a human writing this. What I do see is a human prompting this — and that use case of generative AI fascinates me. “Gas station fried chicken review reply guy” is probably a more representative AI use case than the ones we usually hear about.

I say that because I imagine there’s a reason this person is using ChatGPT instead of writing themselves — and many of us are in that same boat. English might be their second (or third) language, they might not have had attentive teachers growing up, they might be more technically-minded or hands-on, had trouble learning in school or, Bartlebypilled and Scrivenermaxxing, simply “prefer not to.”

And then, ChatGPT came along. It has entered daily life as a filler of that gap. The machine makes you sound nice, smart, and proper. It’s free to use, it works immediately, and it gets the job done. It’s more patient than your teachers ever were, more encouraging than your parents, more attentive and available to you than any therapist.

In a recent New Yorker article, college professor Graham Burnett described using ChatGPT in a humanities course on the history of attention. He assigned a project to his students to ask ChatGPT about attention, and one young woman reported:

“…it was so patient… I was asking it about the history of attention, but five minutes in I realized: I don’t think anyone has ever paid such pure attention to me and my thinking and my questions . . . ever. It’s made me rethink all my interactions with people.”

The gas station fried chicken employee likely feels the same way. And for so many people in our culture who have rarely been paid attention to, ChatGPT is the ideal interlocutor. This is part of why some of them sincerely believe AI can write a great novel or run the world: when they use AI, it makes their own voice sound more articulate than they have ever heard it before. When they talk to AI, it treats them better than real people usually do. It recognizes and cares for them more than others have. These folks are not stupid, but their relationship to the AI is — to my eyes — indicative of a broader social problem.

In a culture where care has been made artificially scarce and attention digitally fracked to the point of poisoning the wells it bubbles up from, what ChatGPT offers is a kind of net to catch the people who fall through. It will care for and pay attention to those of us the system is no longer capable of serving and those of us whom the people in power don’t want to help.

And I mean this in a literal sense:

In the next few years, we will see an elder care crisis as Boomers age. Who will pay attention to all the old people? Having AI do it will be cheaper and easier than reforming policy, retraining workers, or adjusting systems to match changing conditions.

Already, we live in a loneliness epidemic. Who will keep all the isolated, detached people company? Having AI do it will be easier and cheaper than repairing what has broken in communities.

Currently, our political and economic reality is structured by massive income inequality. Who will deal with the social costs inflicted by the downward mobility of a large proportion of the population? For the billionaires controlling AI, having the robots do it will be preferable to actually paying taxes.

Which is why I think the best comparison for ChatGPT, as it actually exists in our lives in 2025, is McDonald’s. Perhaps it comes to mind because I’m the kind of person who hunts for gas station fried chicken on Google Maps. Or, it’s like that old copypasta, “how to explain something to an American: imagine a hamburger.”

McDonald’s is there when you don’t have time to cook food and don’t have the money to dine out somewhere better. It’s there if you live in a food desert far from a grocery store (as so many people do). It’s easy, it turns away nobody. McDonald’s is there for your stomach in the same way ChatGPT is there for your brain. And sometimes, you crave the odd, artificial taste of it, which isn’t at all like the kind of food you can prepare yourself.

In another sense, McDonald’s is a third place. As Chris Arnade documents, over the last few decades in an increasingly disconnected and lonely America, McDonald’s locations have turned into impromptu community centers. In the comments on the TikTok video I made about this comparison, somebody talked about using McDonald’s as place to warm up in the winter when they had nowhere else to go. In comments on the same video, someone who seemed young talked about using ChatGPT as a companion because they were so lonely and had nobody in their life who would listen to them.

McDonald’s isn’t just a restaurant but a piece of social infrastructure. It exists in the way it does because the system hasn’t allowed for a better method to warm people up in the winter, create community meeting-spots, or offer affordable, fresh food. In the absence of such infrastructures, people fall back on what’s available to them — which is often McDonald’s. The large, multinational business then builds into this dynamic, providing a valuable and necessary set of services while, at the same time, doing nothing to change the structural situation. As Matthew Desmond, a leading scholar of American poverty says, poverty persists in part because it is profitable for some.

McDonald’s is addictive to users and corrosive to public health. The factory farming system which McDonald’s requires ravages our natural resources. McDonald’s homogenizes culture and standardizes food. The franchise model outcompetes other local options. And — as proponents of a higher minimum wage have argued for years — taxpayers subsidize businesses like McDonald’s through the welfare programs which make it possible for them to continue underpaying employees.

The same patterns are at play with ChatGPT. The product is clearly addictive, and its impacts on overall public health seem to be negative (just think of all the stories about ChatGPT psychosis). The energy consumption required by AI will accelerate the climate crisis. Its implementation across society will homogenize culture and erase diversity. And it is heavily subsidized by the government, whether that means tax breaks for data center construction, funding for research, or federal contracts for major players.

It is not controversial to say fast food or AI are greedy and bad, but there is something more interesting — and distressingly normal — than just “bad and greedy” going on here. I think we see a governance model.

In previous posts, like slop capitalism and everything is computer, but how? I have argued that the incentives of platform capitalism mean it is more profitable for companies like Meta to destroy overall value in the system than it is for them to create it or even take it from others. My line of thinking here borrows from Ed Zitron, with his idea of the rot economy and Cory Doctorow’s enshittification. I said:

In order to make everything computer, they have to starve civil society into a shape small enough for computer to swallow. Slop is the online culture front of this war on society.

Meta allows Reels to fill with AI slop for the same reason dictators don’t tend to invest in education and don’t hire based off merit. By degrading the capacity of the public sphere, they prevent the formation of power bases beyond their centralized point of control. Slop is an administrative strategy to run what Yanis Varoufakis calls cloud fiefs, and AI is the tool to implement it. In order to administer a thing as vast and complicated as civil society, their best bet is to scatter, dilute, and weaken it.

But I always felt there was something missing from my formulation: I hadn’t described well enough how it fit within a market logic. Tech platforms are increasingly performing governance functions (or, at least, state capture) but they are still companies with investors. And I think maybe that mechanism lies in the Chat GPT/McDonald’s comparison:

For both McDonald’s and ChatGPT, the social cost they inflict becomes the demand for their services. As the education system worsens (in part because people use AI to cheat) as people get lonelier (in part because everybody’s staring at their screens) as the climate crisis intensifies (aggravated by AI’s energy-intensive development) as jobs are eliminated from the economy (in part by AI) and as income inequality accelerates (turbocharged by tech billionaires) a lot of people will be dislocated. Free or low-cost AI will be the infrastructure they fall back on. This is why Sam Altman mused on the “All-In” podcast, to an audience of Trump-aligned billionaires, about offering “universal basic compute” rather than a universal basic income.

ChatGPT is the lazy, cheap solution to the social damages created by the system that produced it, just like McDonald’s. The hurt it causes becomes the demand to sustain it. Insofar as it is a tool for inflicting social cost, slop (in all forms) doubles as a tool for creating demand.

All of the above does not mean the person using ChatGPT to reply to reviews of their gas station fried chicken is bad or dumb. This is not a question of personal choice — this is not the “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism” meme. Rather, it is a systemic and structural issue.

Analysts working in a left tradition will often say “it’s structural” and leave it there, as if abstracting up to that layer is enough. But to me, saying it’s structural means there are things we can do, but the keyword there is “we.” A political ethics formed around “individual choice” leaves us with “be morally pure, exit society, go to a commune” or “you will eat the bugs and be happy” as the two possible options in this situation. But a political ethics formed around “collective responsibility” offers another option: “step up,” because:

If one arm of the repressive platform strategy is to decrease overall value in the public sphere through slop, then a method of resistance is to produce value, however you know how.

If another arm of the platform strategy is to inflict a social cost in order to manufacture a demand for their product, then a remedy is either to A) prevent that social cost from happening through regulation, law, etc. or B) meet that demand with our own product. Teach the children, accompany the lonely.

If another arm of the platform strategy is to weaponize the husks of the old institutional models it murdered, then a path forward lies not in “preserving norms” that are already dead or relying on discredited old ways, but in making new norms that we can own.

The remedy is to produce countervailing power; to create (or reform) institutions so they are more durable, nimble, and open. I follow critics like

in arguing that institutions in some new, more democratic, and less-stagnated configuration are the only answer we may have. The way to do this is to welcome diversity of all kinds, demand results, operate transparently and, following the maxim of ContraPoints, make and take power — don’t just endlessly critique it.

This perspective is so helpful to me in understanding why people use GenAI from a social/structural view, and not just the reductionist answer that people are lazy and/or dumb. Fire post as always 🔥🔥🔥

This is so insightful. It does seem like people crave something better than AI just like people want something better than McDonalds but they feel overtaxed and are constantly doing the easiest thing to get by. Thanks for the inspiration to keep trying to make something better where I can.