brainrot and the order of things

the "diagrammatic" aesthetic

While filming a video about a genre of Italian-language brainrot which centers around AI-generated images showing chimera hybrids of some animal and a machine or food, I started thinking about the introduction of Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things (1966) (Les mots et les choses is the title in French, literally “words and things”).

The Italian brainrot trend emerged early this year out of an existing meme trend from 2023, tied to an audio that began with the nonsense phrase “Tralalero Tralala” and featured Dwayne the Rock Johnson telling stories. The most viral audio includes a series of offensive blasphemies and then rants, in rhyming couplets, about a worthless son who wastes the whole day playing Minecraft. It was spliced on top of various bizarre images and edits.

The meme trend with animals started in late January or early February by applying this audio to a picture of a shark wearing sneakers, using the flame-burst CapCut feature which is popular in TikTok brainrot right now (if you’re familiar with January’s memes around the Eye of Rah and Chopped Chin, you’ll know the effect). Since then, new audios have been written which do not blaspheme God. An AI voice, often rhyming, describes the AI-generated creature depicted and its story. One of my favorites is Frigo Camelo.

The part of Foucault it made me think of is the very first page of The Order of Things, where he describes the genesis of his project:

This book first arose out of a passage in Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought — our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography — breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things... this passage quotes a “certain Chinese encyclopedia” in which it is written that “animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (1) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.”

Now the “Chinese encyclopedia” is from a 1942 essay by Jorge Luis Borges, and it is not real, as far as anyone can tell. Some scholarly ink has been spilled about the orientalism here — the usage of “China” as a faraway place, with the suggestion of ancientness, to create an unfamiliar vibe where crazy stuff might happen. But for Foucault, the interesting thing is more so the tone and the vibe of the list.

By ordering and classifying the impossible so confidently alongside the real, and seeming to carry on in a logical, sensible way, the list functions as a parody of “our thought.” It pokes fun at modern scientific classifications, the “ordered surfaces” of economics, philosophy, biology, and psychology. The Order of Things is a history of how these sciences developed as discourses, how what Foucault calls the “grids” by which the Western tradition understands the world were constructed in the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries.

Foucault is perhaps most famous for Discipline and Punish (1974) which extends this train of thought to talk about medicine and discipline. Isn’t the division of humans into categories like (a) criminals, (b) law-abiding, (c) sane, (d) insane, (e) high-IQ, (f) “average,” etc. sound a lot like the fictional Chinese encyclopedia’s division of animals into categories like “belonging to the Emperor” and “having just broken the water pitcher”?

Of course, Borges’ Chinese encyclopedia is an exaggerated example that’s meant to be funny. But the laughter it inspires is a knowledge-generating laughter, a “shattering laughter” as Foucault puts it, and I think he would laugh at some of these memes in the same way, had he not died in 1984. Foucault tells the history of how these “grids” were made over time, and how these “grids” in turn made our times because they inform how we understand and act in the world.

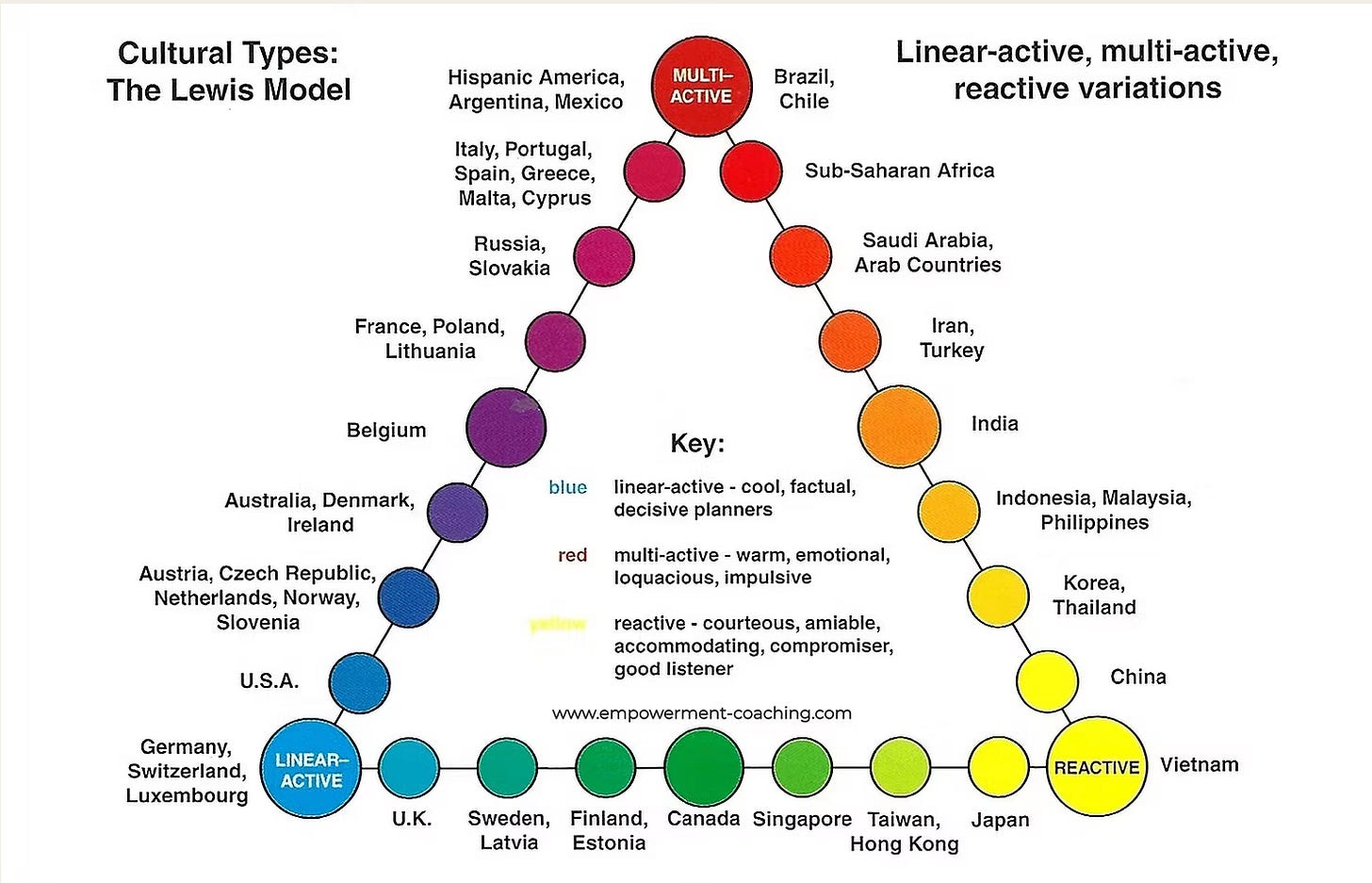

People who criticize Foucault say that arguing knowledge is “constructed” by historical, discursive practice leads to a certain relativism: if everything is a social construct, then nothing is real. But Foucault never says the scientific method is invalid, just that it can’t explain literally everything people do. There is a difference between something like the science behind climate change — which is well-supported by data — and the theories people have in a field like “international relations” or “business” where people regularly create bullshit typologies like Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” or the Lewis Model’s classification of “reactive” and “linear-active” and “multi-active” cultures.

On the one hand, part of what comprises these grids are objective observations about the world and reality. But the grids are also made out of arbitrary historical accidents, bias generated by the motives and prejudices of powerful people, and media forms. “Grids” are influenced by ideology and theology as well: in medieval times, people who displayed behavior we’d classify in our contemporary grid as “insane” might be thought of as “possessed" by a demon or blessed by God. Some have argued the grid is “ideology.”

I am circling back to memes in the next paragraph. Foucault connects this sort of indexical tone and classification language to spatiality. The Chinese encyclopedia of Borges creates a kind of “heterotopia” (literally “other space”) where things are connected through the grid in a way that doesn’t need to correspond to their actual reality. The process of listing, sorting, and categorizing draws the scope and limits of a space which sits, rather awkwardly, on top of our own. I was pulling some ivy off a fence in the backyard, which had its roots on the other side, and thinking about this. The ivy vine understands how space works, but it doesn’t understand the concept of a property line. The property lines are a heterotopia imposed on our real, natural topos just as various schema for disciplining bodies and arranging ideas are imposed on our imaginations and perceptions.

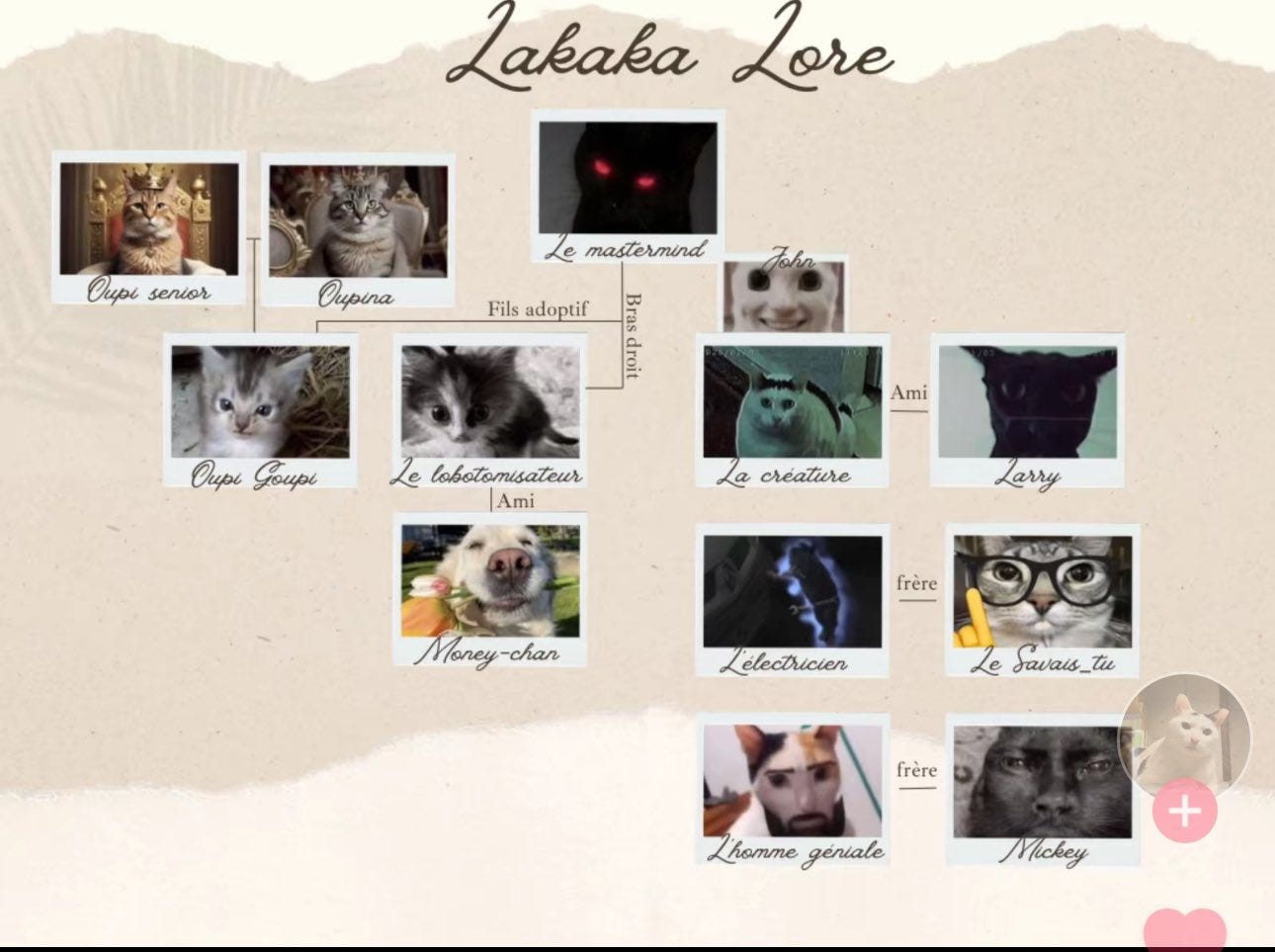

In the Italian brainrot (and other brainrot traditions I have covered) we observe an interest in creating a bunch of ridiculous characters and classifying them according to some schema. In a spinoff trend, users post videos of the different Italian brainrot characters fighting, to determine which will come out on top. This reminds of the al-Rahma Arabic brainrot which places all the meme characters on a bracket and has them battle it out to see who’s the champion, or the Lakaka.land French brainrot which arranges all the characters according to their relative moral standing and their web of relations to each other (which some users have even taken the care to diagram).

There have been many memes which rely on the usage of charts, diagrams, and patently absurd classification schemes. Think of political compass memes, or the bell curve distribution memes. Think of memes which take the visual language of infographics and turn them to funny purposes. There’s an essay I love by Ivana Emily Škoro published by the Institute of Network Cultures at the University of Amsterdam which talks about this kind of “chart meme.” In the Rosalind Krauss essay Grids, which Škoro’s piece alerted me to, we have a description of the grid in twentieth-century art (think Piet Mondrian) which sees them a “myth” and visual symbol that acts similarly to what Foucault says conceptual, heterotopic “grids” do:

… the grid is a way of abrogating the claims of natural objects to have an order particular to themselves; the relationships in the aesthetic field are shown by the grid to be in a world apart and, with respect to natural objects, to be both prior and final. The grid declares the space of art to be at once autonomous and autotelic.

Following Škoro, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to see the recurrence of grids and charts in memes in a similar way. I was chatting a little while back with Leslie Liu, an artist and designer who has made some really compelling work around memes. From a visual perspective, they’re interested in what we called the “diagrammatic” aesthetic in memes — the discipline of “top text / bottom text,” the placement of specific things in specific places that seems to be core to many meme formats, particularly image-based memes.

There is a pleasure to arranging things — it’s the same pleasure you feel when you clean your room and there’s a place for everything and everything is in its place. But there’s also a gesture going on in these memes that’s similar to Borges’ Chinese encyclopedia — by creating an absurd, bizarre grid, brainrot and absurd memes point to the ways that our own grids (whether literal or conceptual) are questionable and don’t have to weigh on us as heavily as they do.

This is what a lot of abstraction in art does for me. It makes me see my own seeing, read my own reading, hear my own listening. And it reminds me that we can always see, hear, or read otherwise — that our selves and the world beyond are not actually bounded by the discourses which others have made to enclose and envelop them, to discipline and order people.

For this reason, I have been a staunch defender of brainrot as a form of art: it creates that “shattering laughter” which Foucault writes of, by exposing how in many ways the real brainrot is the manner of living we call “normal.”

thank you so much for this — rushing to read that Kraus essay, seriously. In my efforts to do some armchair psychoanalysis around the aesthetic experience of CAPTCHAs, I wonder how you'd compare image-based CAPTCHA (identify motorcyles) and brainrot? While difficult (at least for me) to trace what machine learning models we are materially training, it feels like an iteration of the diagramming instinct/impulse you mention here.

There's this Are.na user Institute of Diagram Studies (https://www.are.na/institute-of-diagram-studies/index) whose diagram channels I think of every now and then, especially in conjunction with the QAnon map that Contrapoints covered in her recent video essay on conspiracy. A while ago a friend and I had tried to design a similar map that would somehow fit in the totality, absurdity, and cultural-political underpinnings of contemporary American life; we'd gathered similar diagrams that felt "potent" and "insistent on some form of truth telling/soothsaying" — much in the same vein that "Truth Social" posting is called "Truthing", as I hear.

I wonder if there is something fundamental about our relationship with images such that we always seek to extract or ingrain a personally defined "meaning" from/into them — but with rapid rates of meme transmission, duplication, and creation, we often forget the subjective nature of such "meaning" (see Michael Reddy's Conduit Metaphor — https://www.are.na/block/14588445)

An aside: found this "Composable Meme" channel (https://www.are.na/sam-hart/composable-meme) by Sam Hart that may be relevant.

Back to this ramble though, this post also brings to mind what Rob Kitchin in The Data Revolution (2014) writes,

"Given advances in storage capacity, it seems we have reached the stage where in many cases it is easier to record everything, than to sort, sift and sample the data, recording only that which is potentially useful (and who is to know what might prove to be useful in the future?)."

The last part of this — "who knows what might be useful in the future?" — drives a lot of the preciousness around diagramming I feel; also so key to the financialization of memes (what is a memecoin but a desire to be able to see your taste, sensibility, and expression of your positionality reflected and belonging? — and also even in smaller ways, how people [at least a while ago, it's been a minute since I last used TikTok] stake a claim to "investing" in memes "early on"). I've got another tab open for your slop capitalism essay, but that "firstness" (also refer to https://www.heliotropejournal.net/helio/firsting-in-research) is something I think we can really unpack. Is the participatory, competitive nature of collective meaning making somehow sidestepped altogether in slop media?