"algorithmic gaze," continued

rebellions of technology and messianic time

This post continues the line of thinking in last month’s algorithmic gaze, taking up what to me has always been the most difficult-to-interpret part of Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935). I’ll put it here (it’s the last paragraph of the essay) so you have the thing itself instead of a paraphrase:

“Fiat ars—pereat mundus” (make art, let the world perish) says Fascism, and, as Marinetti (author of the Italian Futurist manifesto) admits, expects war to supply the artistic gratification of a sense perception that has been changed by technology. This is evidently the consummation of “l’art pour l’art.” Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.

What I want to do is look at our current “situation of politics” and consider what art (and memes most particularly) can do. First, how does the “situation of politics” and technology’s relation to it in Benjamin’s day compare to our own? Second, what does it mean for Fascism to “render politics aesthetic” and for Communism (Benjamin’s chosen path, but I’m understanding it as “anti-fascism” more broadly) to respond by doing the inverse and “politicizing art,” and what might memes and history have to do with this?

the “situation of politics”

What makes the epilogue of the essay difficult-to-interpret for me is the way it shifts us from the realm of “abstract theory” into something which feels like an opinion editorial: the subject matter is unavoidably specific and political. Benjamin wrote the essay in 1935, two years into exile from his native Germany and five years before he would flee occupied Paris, seeking refuge in the United States. His group of refugees were stopped after illegally crossing the border by Spanish police, who said they would be deported in the morning and handed over to the Germans. Benjamin was a Jew, and knew what would happen if the Germans arrested him. He killed himself that night with an overdose of morphine.

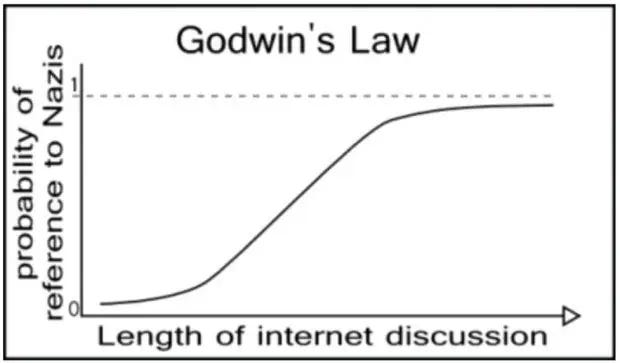

The first thing called a “meme” by the modern definition was Godwin’s Law, which the eponymous Godwin described in a Wired magazine article in 1994. He started using it as a phrase on chatrooms when people kept making comparisons between present events and the Third Reich — a kind of historical illiteracy which bothered him. Godwin’s Law goes: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.”

Godwin called his law a “countermeme” to be used against the “meme” of Nazi-comparison in these chatrooms, and he called his invention of the law “an experiment in memetic engineering.” In 2023, Godwin published an op-ed in the Washington Post titled “Yes, it's okay to compare Trump to Hitler. Don't let me stop you.” So, keeping that in mind:

In 1935, cinema was forty years old and Walter Benjamin was forty-three. The first Hollywood films had come out right before World War I, and the first sound film was released in 1927. Film, and mechanical reproduction of artworks in general, was no longer new at the time Benjamin wrote about it, but neither was it old. The first wave of careers had been made, the first movements and schools had risen and fallen.

In 2025, internet culture stands at a similar point in its evolution: a generation (Millennials) have grown up alongside it, and a younger generation (Zoomers) has grown up inside it. The civilizational structure made by the internet is emerging, and the older forms of politics no longer apply. There are many ways in which the 1930s and today can’t be compared — but I think in this respect, we see a rhyme.

Benjamin couldn’t help but understand film (and mass-reproduced culture more broadly) in the light of his political situation, and I don’t think we can understand memes (or algorithmic culture more broadly) without considering our own political situation. A violent regime that wants to hurt people is dismantling the world you grew up in. The ways of looking and being created through the internet have something to do with how that happened — just as Benjamin and his peers thought film had something to do with the rise of fascism.

In the epilogue of the essay, Benjamin sketches out a theory as to how fascism is tied up with new forms of media, and he identifies war and violence as the crucial link.

As new ways of being and seeing disrupt everything around us, Benjamin asks, how do our rulers maintain control? How can we experience such radical changes in the texture of our day-to-day lives, in the composition of our fantasies, and in the nature of our bonds (real or imagined) with other people, yet still have capitalism?

The answer to this problem, for him, is fascism and war. In a material sense, overproduction in the economy is solved by making things you will immediately destroy (or having others destroy the stuff you make). Spiritually (or, if you prefer, culturally or psychologically) the anger, listlessness, confusion, and despair which people feel because of these changes is funneled into hatred of others.

Benjamin argues that since the “property system” and capitalism writ large can’t really contain technology and its productive capacity, the technology will either destroy capitalism (and we get Communism) or it will destroy people (what Benjamin calls the “unnatural utilization” of war). War is the only way to continue the development of technology without overturning the property system.

Imperialistic war is a rebellion of technology which collects, in the form of “human material,” the claims to which society has denied its natural material. Instead of draining rivers, society directs a human stream into a bed of trenches; instead of dropping seeds from airplanes, it drops incendiary bombs over cities; and through gas warfare the aura is abolished in a new way.

One thing I often think about is the zone rouge, a span of land across northeastern France where the trenches of the Western front were dug and for four years the most advanced armies in the world shot at each other. An area roughly the size of Paris remains forbidden for people to enter to this day. In several places, nothing can grow because the content of the soil is full of arsenic from chemical weapons. Groundwater in northern France is occasionally poisoned well into the 21st century by toxic chemicals that seep out of the shells. Every year, farmers in this area collect an “iron harvest” of hundreds of tons of unexploded ordnance. Experts estimate that it would take 300 to 700 years of diligent effort to remove all the shells from the soil.

From a macroeconomic perspective, war at this scale is a gross inefficiency — how many bridges and cars could have been built with the metal that made those bombs, how many inventions might have been made by the people who died in those trenches — but it is also a result of incentives that become misaligned with reality, and end up making people a lot of money.

Compare the zone rouge to other regions of the Earth which human violence is currently rendering uninhabitable — the oceans sloshing with microplastics, the ecosystems destroyed by desertification, the farmland that grows nothing, leading its inhabitants to risk a desperate journey to some place they might make a living. The zone rouge was a train ride away from Benjamin as he wrote The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, just as a zone of ecological devastation is likely a train ride away from you.

What Benjamin suggests is to see this devastation not as industry’s cost or collateral damage, but as its perverted goal. When you can no longer profit from production, you profit from destruction. And this point isn’t just a leftist critique — the new Prime Minister of Canada Mark Carney, who was a central banker, writes something similar in his book Value(s) about the way “objective valuation” of what matters to us as humans (things like life, productivity, rights, the environment) is overwhelmed by the “subjective valuation” of the market as it is currently set up, leading to a situation where, across the economy, we destroy rather than produce. I twist Carney’s argument a bit to match it to Benjamin’s, but I think the fundamentals are the same.

Finance and tech, which run the economy today, are not incentivized to create value, but to prey upon existing sources of value. Apps destroy stable work, communities, and institutions by turning them into gigs and games. Meanwhile, industry destroys the environment and fossil fuel firms reap record profits, proving that poison sells better than medicine. Monopolistic platforms interject themselves into every interaction, gobbling up small and medium sized businesses alongside the lifeworlds of print, face-to-face conversation, and brick-and-mortar. Tech firms mean to change the way humans work, learn, raise children, date, travel, love, govern, think, feel, read, and assemble — but not the way they own things. The phone in your pocket gnaws away at every institution of society except for a 1980s-style consensus about property relations and capital. Everything can be reimagined except for the primacy of capital over the other two factors of production, human labor and nature.

And so, if the two ingredients for fascism in Benjamin’s final analysis are a violent cannibalization of value, human life, and nature (as represented, in his era, by things like the zone rouge and the Dust Bowl) plus a new media form that alters the ontologies and epistemologies by which people live in the world, then we have those two ingredients in our own society, don’t we?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How To Do Things With Memes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.