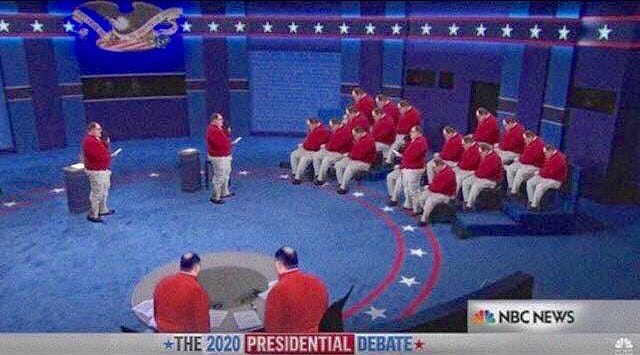

In the beginning he was, as so many of us are, just a guy with a question. For his big night on national TV, he picked out the kind of outfit folks wear to church: khakis, a white collared shirt, a red cardigan sweater. I imagine he practiced his question in the mirror, to be sure he wouldn’t stumble over his words when the cameras were on.

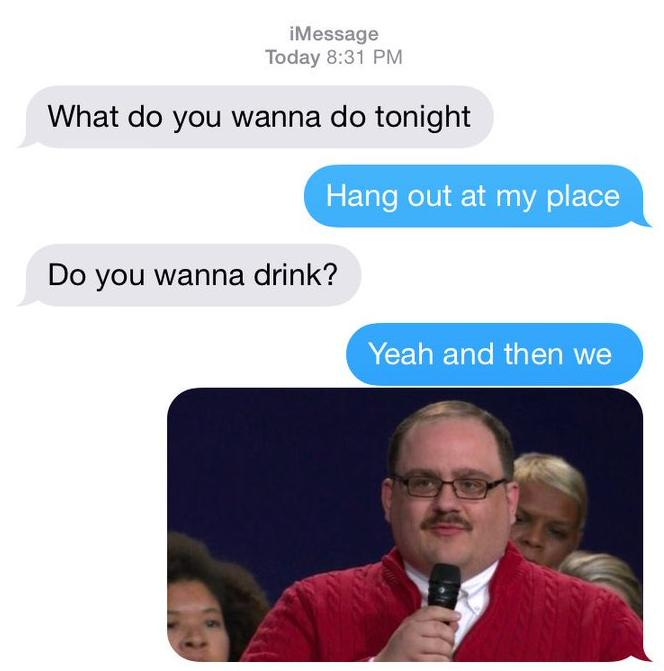

You likely don’t remember what Ken Bone’s question to Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton at the second presidential debate in October 2016 actually was (it was about energy policy) because the more important thing was his face. That face which launched a thousand memes. On that fateful evening, something broke within the American mind and Ken Bone rose as the avatar of that break.

On some level, all memes are political insofar as they are demonstrations of the swarm’s power. Something gains visibility because we want it to, not because it’s the most relevant or appropriate thing, not because it serves someone’s agenda. Despite the obvious co-optation of algorithms and other online power brokers, the idea at least of this democratic impulse is central to internet culture. And it defines itself in opposition to other ways of telling our national story.

Publicly declaring you wanted to fuck Bone, worship Bone, abandon the candidates on offer for the gentle encompassing embrace of Bone, was a way of refusing to interpret authority’s story in the way authority wanted it to be interpreted. It was a way of performing your defiance to the most powerful narrators of public life. I see a similar gesture at play in Luigi Mangione memes, as I’ve described in previous posts. Sharing memes about the mug shot and wanted poster as thirst traps means rejecting the way the media and cops wanted you to understand these images and the story they showed.

How television worked for politics

The medium through which that story has been told, for the past few decades, was television. American democracy as it existed until recently can’t be understood without understanding television — and neither should its breakdown be understood as separate from the medium’s decline. The media studies cliché is that JFK won the 1960 election because he looked prettier on TV than Nixon did, but it goes deeper than that. Television created rituals which determined the shape of institutions: the State of the Union, party conventions, Presidential debates, the 24/7 news cycle. It aestheticized politics and limited us to specific forms of discourse (sound bite, cable news hit, “hardball” interview with a journalist). It also suggested an attitude for us as citizens watching: a passivity which, by means of strong parasocial attachment, lies itself into thinking it counts as participation.

But now, in the age of social media, ritual performances of authority on television ring hollow as the gestures of a royal coronation, which once imparted a divine energy but now look like theater. We know the man behind the desk doesn’t talk like that in real life. The fact he puts on that specific vocal performance no longer serves to make him sound more audible (as it did in the days of radio or early TV, when audio was fuzzier) nor does it serve to make him seem smarter, more trustworthy. It just makes him sound silly to anyone under thirty, and to many people over thirty too.

This is not to say the alternative — social media — is any more “authentic,” or less “ritualistic.” It’s just a different kind of performance, equally artful. The reason people call out the “millennial pause,” that inevitable moment between pressing record on your phone camera and beginning to talk, which most Zoomers know instinctually to cut out of any video they post, is because it is a moment of authenticity that doesn’t follow the rules of the form. This new form and its new rituals has replaced television as the dominant moving-image and informational medium in our culture.

As the old rituals lose their meaning, so do the patterns of thought bound up with them. Anchors and pollsters may be nonpartisan, but people know they aren’t apolitical. They determined where attention should turn according to priorities that represent the interests of their caste (generally speaking, educated, upper-middle-class white liberals). They also represented an implicit set of ideological convictions that up until recently neither party questioned — making these things feel like “common sense” rather than “political opinion,” stuff like support for Israel, support for free trade, not talking about income inequality, etc. All this stuff is now falling apart. I’m not suggesting there is a conspiracy here, what I am suggesting is there was an institution.

Any ritual is embedded in time. A presidential term is four years and the television media marked each point in that span with particular kinds of ritualized coverage: the Inauguration, the hundred days retrospective, the State of the Union, speculation about who will run next time, the midterms, Iowa and New Hampshire primaries, Super Tuesday, the party conventions, the debates, and finally election night. This functioned like the liturgical calendar of holidays and festivals did for medieval peasants, serving not only to inform Americans about what was going on, but to structure our sense of history and stage a series of legitimating exercises for the regime.

For decades, the real substance of our politics was the continuing resolution to find these televised spectacles relevant — and that’s a problem, because it kept us from thinking the real substance of politics might be marches, protests, civic organizations, and forums where our own voices can be heard.

Ken Bone was a moment where one particular ritual cracked.

The presidential town hall debate

The first presidential town hall debate was held in 1992, requested by Bill Clinton, who believed “real people” wouldn’t ask him to talk about sex with women he wasn’t married to, while reporters would.

In addition to giving Bill an easy out, the presence of “everyday people” like the folks watching TV helped in an election cycle defined by populism. 1992, as John Ganz documents in his book When the Clock Broke, was a crisis year that saw a surge of rowdy freak energy. Demonstrating mainstream politicians listened to Americans was necessary for the continuation of a threatened political system. The town hall debate stuck around after 1992, becoming a regular feature of the election ritual.

Participants for town hall debates are chosen to represent America, carefully selected for every kind of diversity (as the network understands it) except one: they are all undecided voters. The audience will incarnate types of citizen you know exist. A female audience member will ask the candidates about abortion, a Black participant will ask about police reform, an older one about social security. Ken Bone was introduced as a white male midwestern factory worker—a member of the constituency that apparently flipped for Trump and since been cartoonified in countless ethnographies scribbled by Politico reporters in far-flung diners across the heartland. We were supposed to see Bone as representing a type, a genre of man understood to exist in the political discourse — this was his ritual function.

But we refused to see a blue collar worker, a white man, or a Midwesterner. What we insisted on seeing was Ken Bone, a guy who happened to be all these things but was most of all Ken fucking Bone. Rather than looking through Bone, we, the 66.5 million watching the debate looked at him.

Within seconds of setting down the microphone, Twitter turned Ken Bone into a sex symbol, a presidential candidate, and internet-famous culture hero. People started tweeting about him and then arguing about those tweets before the debate even finished—which meant a lot of them were no longer giving it their full attention.

The admiration of Bone was deeply ironic. Traits which he later told a reporter gave him “a very low self-image”—his weight, his mild manner, his receding hairline, the last name he was definitely teased about in school—became the reasons for his fame. Exalting Bone for so supremely failing to conform to the expectations for an American man on television was subversive in its own way, another means of rejecting the spectacle of the town hall debate. Twitter’s embrace of Bone was a welcoming of what American television excluded: fatness, sensitive men, crude sex jokes, and sincerity.

So, you have to see within the Ken Bone meme not just defiance but a kind of hope. In 2016, people hoped our national story wouldn’t have to be bound by the constraints of television. And maybe there’s still hope. We don’t have to live by yesterday’s magic.

Online Rituals

Online culture offers its own types of legitimating ritual. Take, for an example, the format of a Joe Rogan interview. As Rogan has described it, his goal is “to see how someone’s mind works.” It’s not like a Sunday show interview, where a reporter asks tough questions to outmaneuver the publicity spin of a politician and find what’s actually underneath it, a rhetorical dance that for decades has made great television. What Rogan does is create a situation where you spend three hours, casually, with him and the person he’s interviewing.

Of course, Rogan’s casualness is as fake as the reporter’s confrontation. But it is a ritual, with its own result. When public figures are famous for being “authentic,” people feel there’s a baked-in accountability: you know that, as a listener, you made them. You don’t get that sense with most politicians, because somebody else made them — namely, the people who run the TV.

What Rogan also offers, as a posture for the viewer, is the role of “companion.” He is like you. The best Rogan interviews are when he gets some physicist on and asks the sorts of questions someone who knows nothing about the topic would ask. For most of us, we know nothing about the topic and so he feels like kin.

And that is where the impact of these rituals is most fully-felt: as a kind of companionship. Politics must produce meaning. In a country where religiosity is in decline, economic inequality and climate crisis strain communities, and new communications technology has reshaped social life to leave more of us lonely and most of us angry, we need some form of politics to keep us in this life and with each other. And so the Ken Bone memes are not just about defiance, but about a hope I think is still alive in 2025. The goal can’t be to make a Joe Rogan of the left, it must be to make a new set of rituals to enframe public life, and develop new forms to communicate with each other.

Hope is a confrontational affect, it looks at reality and asks why it cannot be otherwise. Hope is not a soft yearning for a better life, it has — as a young Senator from Illinois once phrased it — “audacity.”

This misses a key part of the Ken Bone saga, his downfall, spurred on entirely by him using his personal reddit account for an AMA, through which we learned he was thumbs down on Trayvon Martin and thumbs up on sex with pregnant women

The medium is the message. Shoutout to Marshall McLuhan. Great read and great analysis!