I started watching Skibidi Toilet as a bit because I thought it might do well on TikTok. I’m just gonna be honest with you there. My analysis videos of the show performed well, and I found myself continuing to create them.

But over time something strange started happening: I became sincerely interested in Skibidi Toilet as a show. It was no longer just “here’s this representative freaky media product of Gen Alpha” but “here’s a work of art that’s actually changing my view of the world.”

I started noticing CCTV surveillance cameras perched in the corners of my vision more frequently, because they reminded me of the camera headed soldiers in Skibidi Toilet. I watched dancers in music videos and their movements would remind me of the pyrotechnic ballet which the show’s cyborg-titans take part in. And as I watched Skibidi Toilet’s later seasons, where DaFuqBoom!!! extends beyond the thirty-second YouTube Shorts format into longer-form more visually adventurous 16:9 horizontal videos meant to play on a laptop, I started getting this uncomfortable feeling that I’d never felt anywhere else.

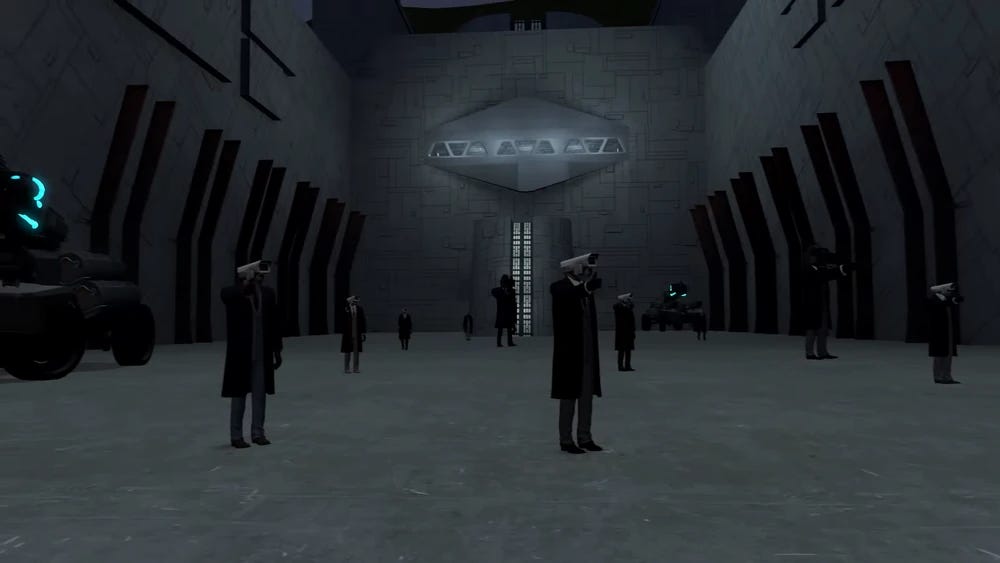

It was a feeling of eeriness, fear, and unease. Skibidi Toilet shows a futuristic war from the vantage point of an infantryman. The show’s visuals are uniformly gloomy and dark. The sky extends over your head, blank and vast, ringed by hollow skyscrapers. There is absolute silence save for the rumblings of far explosions and then the cataclysmic blasts of nearer ones. No spoken language happens in the Skibidiverse: its horrors are beyond words. There is just the endless clashing of inarticulate machines, speaking in no tongue besides the lapping tongues of flame and smoke that swallow them all, endlessly.

This specific vibe was something I’d never felt from any other piece of media until I saw this ad (seen below) for Palantir, Peter Thiel’s defense contracting firm, which aired during the Army-Navy football game attended by JD Vance, Donald Trump, Elon Musk, and Daniel Penny. Images of the new regime’s principal men watching the game circulated widely across social media, as did the very clear corporate sponsorship signs by Palantir. But this ad is what stuck with me most.

“The Future of Warfare,” as the ad is titled, is giving Skibidi. The gloomy, wordless depiction of violence carried out by machines. Shots of conflict as seen from the POV of drones and automated soldiers. Humans visible only as a shadowed face, a finger reaching to push a button or — most strikingly — a conductor holding a baton to direct an orchestra of drones that swarm like birds and swoop down upon an enemy. This aesthetic is giving Skibidi.

It is one of the ways that I find Skibidi Toilet deeply moving and prescient. It is a vision of the future marked by metallic violence, electric brutality. It is a future where surveillance and automation bring about horror, and the view of the world through a camera no longer amuses but accuses instead.

Skibidi Toilet casts the viewer as a soldier complicit in making a dystopia. The entire show is filmed through an infantryman Camerahead’s POV. In a strange way, the camera head POV both embodies and disembodies the viewer. It glances and turns in response to a sound, perfectly mirroring the way our attention may move, feeling almost as if we’re wearing a headset rather than looking at a screen — but then at the same time, it operates in ways human vision cannot: it never blinks, and it can zoom in and out.

The POV camera head also muddles our feeling of action — it may seem to embody us, matching the pace and flow of our shifting gaze, but at the same time we (or rather it) are doing things we don’t choose or understand. Watching Skibidi Toilet feels like a walking dream, a trance — we as viewers are like the cyborg, unable to choose where to place our bodies and attention even as it seems we are doing the moving and watching. This is most striking when the POV camera head flushes, punches, or tortures Skibidi Toilets. We have no choice but to experience these events as if we are the culprit.

The third-person camera, which seems to be a kind of objective observer, is what we’re used to in film and television. But the Skibidi Toilet camerahead offers a view of the world that is never objective. It is instead subjective in a cold, disinterested sense: it is here not to narrate, but to do as it is told and carry us along.

The Palantir ad’s catchphrase is “Battles are won before they begin.” The implication being that Palantir can turn war into a certain science: if enough drones are deployed and programmed correctly, the enemy will have no chance. The battlefield outcome will be as sure as the execution of a package of code. No human mushiness can intrude.

Robot war promises an immaculately legible form of violence. It will kill the way a washing machine cleans dishes. It will do it according to clear parameters, time frames, and methods. This kind of war is thoroughly documented, intelligently forecast, perfectly reasonable — or at least this is the image Palantir sells. It is a fantasy not only of glorified, aestheticized violence (it’s giving futurism) but also of rational legibility.

Reality will follow the plan exactly, Palantir promises. The data-driven explanation will match the lived experience, with no part of the world surpassing what drones can target and computers can scan. It’s Seeing Like A State-coded.

Skibidi Toilet presents a world where the construction of increasingly intricate technologies leads to an endless and emotionless forever war. ‘Bloodbath’ isn’t the right word because there is no blood, only machine parts. Instead of a conflict with stakes and objectives (we never learn what these might be, after all) we have a weird symbiosis: one side destroys the other in exact proportion to how well it has already been destroyed. The purpose of each side is to destroy the other and nothing else. The robots are all so good at killing each other that they can never stop killing each other.

What the Palantir ad and Skibidi Toilet both imagine is technology triumphing over the human experience, not over some foreign adversary. This is what is so eerie and illustrative about the show to me, and —I’d argue — a major source of its popularity. Gen Alpha sees the signs of skibidystopia, it is a fictional world that mirrors the troubles of the real world.

In the skipidarkness of the future, there is only war