ON SKIBIDI, part two

a critical analysis

This is a draft of a second section of the pamphlet I will publish about Skibidi Toilet likely by the end of the year. If you are a paid subscriber, I’ll do my utmost to get you a copy of it for free, in print, if you’d like one —and I will be in touch about that at a later date. For others, it will be available on Metalabel for a very affordable price, and I will post the link when it is out.

The First-Person Camera

The entirety of Skibidi Toilet is filmed from the perspective of one of the CCTV camerahead infantryman footsoldiers. Almost every episode of the series ends either with a toilet killing the POV camerahead (and by extension you) or else with one of the other Media Alliance members giving it (and by extension, you) a thumbs-up of recognition, of complicity. Both these techniques serve to involve and immerse the viewer.

The most proximate reference is first-person shooter games. Skibidi Toilet looks like the kind of gameplay footage —walkthroughs, screen recordings of streamers and so on—which is everywhere across YouTube. People sometimes watch game footage as if it were a film, or play games in order to follow a story and feel interactively engaged — and so Skibidi Toilet fits well into this particular strain of visual culture, which certainly makes up a higher proportion of all that Gen Alpha sees in terms of manufactured images than it does for older people, even for Gen Z. The Half-Life 2 assets used in the series, which are from a video game, are also designed to look good when viewed and rendered in this way.

Every shot in the series is taken on a camera that is real within the world of the show. Everything we see goes through the camerahead’s eyes, or, rather, lens. And that lens, as the show demonstrates, is biased, fragile, and limited. There are no cuts within an episode, meaning each one is composed of a continuous POV shot — a slice of synchronous visual experience which identifies the viewer with the camerahead spatially and temporally: our vantage point is from within his body, and our experience of duration matches his own.

However, we are constantly reminded by the lack of a visual periphery which the 9x16 aspect ratio of vertical video demands as well as the use of the hard zooms which recur from episode to episode (and, to some extent, are a retention tactic increasing visual variation within the video) that the camerahead’s visual apparatus does not match our own. It does things our eyes don’t do, although it corresponds to our hardware in some ways: Skibidi Toilet is filmed from the perspective of a two-legged creature of roughly human size, occurs in a typically urban setting that isn’t too far off from the places we live, and happens through a continuous, unbroken span of time, just as our own seeing does.

The result of this balancing act between the mimicking of our visual experience and the departure from it is a constant dance between immersion and estrangement. We see as the camerahead in a viscerally intimate way, but at the same time we are constantly reminded that the camerahead’s own subjectivity intervenes in the image we see. The visual field turns grainy when the Camerahead is hit, zooms in when the Camerahead is curious. It is never an image without a motive, nor is it an image with the authority and detachment of a third-person narrator. And the image is always showing us two things: first, whatever is onscreen, and second, the Camerahead’s reaction.

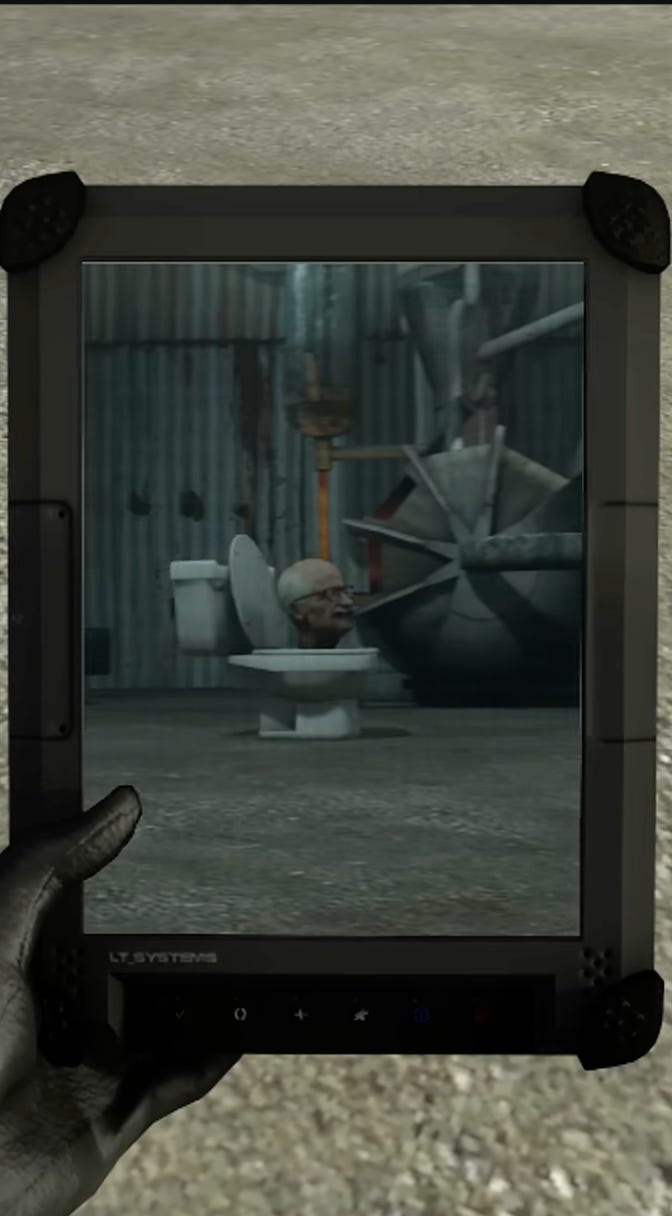

In Skibidi Toilet 16, a 17-second reel produced early in the show’s run, the complications (and narrative possibilities) of the first-person camera perspective are explored to particularly illustrative effect. The opening of the video has us looking down at a CCTV camerahead inside of a toilet, and then shows an arm belonging to our POV camerahead character pointing towards a building labelled with a picture of Skibidi Toilets. The CCTV camerahead toilet — a type of drone, essentially, created by the Media Alliance for reconnaissance purposes — enters into the building and our POV camerahead watches what seems to be a live feed, captured by the CCTV toilet on an iPad. The camouflaged CCTV toilet records Skibidi Toilets milling about, but the ruse is quickly found out. Our POV camerahead watches on the iPad as the Skibidis take out the CCTV toilet. Seconds later, the iPad is dropped and the toilets take out our narrator.

In the short, we watch a camera watch another camera, forming a matryoshka doll or mise-en-abime of images framing other images. The camerahead’s gesture, holding the iPad, mirrors the viewer’s gesture. Another mirroring happens when the footage on the iPad blurs out as the CCTV-toilet is destroyed, and seconds later our narrator faces the same fate. This entanglement of narrative planes is symptomatic of broader trends within digital culture.

Frequently, with vertical video content on social media, we are not really watching something so much as we are watching someone’s watching of something. The framing, the reframing, and any disparity or tension between the two form the emotional core of a lot of the content we’re seeing. We watch through influencers just as we watch through the CCTV camerahead in Skibidi Toilet.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How To Do Things With Memes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.