At White Sands National Park in New Mexico, there are several sets of early human footprints, tens of thousands of years old, embedded in sedimented mud flats. As the park’s website says, back in the Ice Age “the climate was less arid, and the vegetation was abundant. One could have seen grasslands stretching for miles that would have looked more like the prairies of the Midwest rather than New Mexico’s deserts.”

One set of footprints, discovered this century, appears to be from a female (or possibly adolescent male) walking with a toddler. According to an article by Karen Coates in Archaeology Magazine:

The researchers concluded that the chaperone on the excursion at times carried the toddler, shifting the child from hip to hip. This subtle change in behavior is reflected in the alternating shape of the footprints, which broaden with added weight to form a banana shape created by the outward rotation of the older person’s foot. They can also tell this was a speedy trip, completed at a pace of 5.5 feet per second through slick mud—far faster than that of a person walking at a comfortable pace of four feet per second over dry, flat land. They determined this by creating a mosaic of aerial images of a large section of the trackway that encompassed hundreds of prints. This allowed them to calculate the people’s average stride lengths.

The tracks appear to go out in one direction and then turn around and come back, covering about a mile. “Between the outbound and return legs of the trip, a giant ground sloth and a mammoth crossed the pathway. The mammoth walked in a straight line, leaving no evidence of having noticed, or cared, that humans were in the vicinity.”

You may wonder why this woman with a child on her hip, thousands of years ago, walked so quickly away only to turn back around. Her motives are remote to us — was she fleeing something and realized her way out wasn’t there? Did she see another mammoth, blocking her?

And yet, from a close analysis of her stride and the shifting of her feet in the mud, we know a few things and may infer others with certainty: her size and build, the heaviness of her breath walking at speed, the weight of the child who she switched from hip to hip as you might a heavy bag for groceries from hand to hand, before needing to set the kid down for a few moments on his own feet.

This is the way our phones know us. They watch our paths across their world the way we watch fossilized footsteps across ours. The phone does not understand why we go one place, turn around and come back. It does not know why we go so quickly, what we leave behind or intend to arrive at. But it does infer, from traces left intentionally and not, the shape of our world. It notices details which we ourselves, in the flow of experience, ignore: the “banana shape created by the outward rotation” of the foot, the lingering of your finger on the egirl’s face. It draws inferences and patterns. It begins to speculate on social structure and kinship networks from the collection of footsteps left in mud.

As social scientists Kevin Munger has described in his piece on the “sensorium of the iPhone,” the phone is not listening to your conversation with a friend and then, days later, serving you a Facebook ad tailored to exactly what you were discussing. The phone does not have ears. But what the phone does have is a sense of which WiFi network it has connected to, the status of other phones that it has met in the digital ether, the searches it and those other phones have performed. It knows the parts of ourselves which we don’t know, and cannot really understand the parts of ourselves which we are actually most interested in.

“(The phone’s) memory is precise and stupid,” writes Munger. It does not “think” or “see” as we do. It “does not navigate the medium-size world of tables and chairs but the precise grid of the surface of the globe.” Its two on-board sensory organs are its ever-sensitive screen and its proprioception, which is supplied by an internal gyroscope and a connection to a sprawling satellite network.

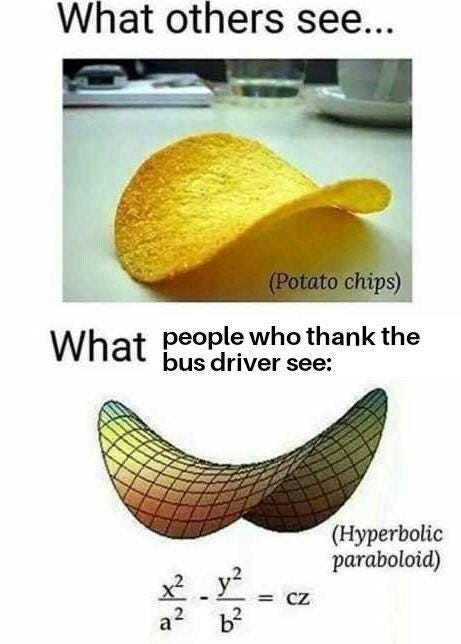

The phone, or any kind of surveillance tech, is like an ant bringing its little crumb of you back to the colony. The queen is a system sitting ensconced in a data center. It does not “see,” does not “speak,” and does not “listen.” Thanking ChatGPT is not the same as thanking the bus driver.

The representations of the world which matter most — the ones we must accommodate, anticipate, and navigate by — are tailored to the phone’s sensory experience rather than ours. Streets, systems, content, and markets are optimized to be legible for the phone first and the user second. Structural conditions allowed for this drift: any Foucault-enjoyer will tell you that modern power relies on legibility, intimacy, and standardization, and the phone is a tool that offers that in spades. There’s also a case to be made, by people like Brian Merchant, that tech solutions such as Waymo self-driving cars are “accountability sinks,” attractive instruments for states (or corporations that act like states) to evade legal responsibility and banalize the evil they may do.

Some may argue that what happened here was production colonized play, the two zones congealed in the shape of the smartphone that offers instant connection to both Instagram and the work email inbox. Because of the phone, the laboring day no longer runs from 9 to 5 but includes the 8:17 PM question from Karen about where we are on that project, which makes your phone tremble the table midsentence as you wait for your drink to arrive.

Another variant of this is the argument made by technology ethicist Tristan Harris in The Social Dilemma, a 2020 Netflix documentary: “when you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.” That phrase is adapted from a 1970s critique of television advertising. Play, alongside all else, turned into a form of production, through which we ourselves were produced.

The surveillance infrastructure of Instagram, the email app, and the dating app you used to arrange dinner and drinks with this guy each import the market into personal life. They are all watching you and selling some version of you to other people. Your sleeplessness, your moment on the toilet, and your nostalgia for a vanished past are chopped to sellable bits and trafficked by algorithms. Experiences, the building-blocks of character, are scanned and sold like “orange juice futures or corn yields” (Zadie Smith).

Previously informal social spheres become pay-to-play panopticae: he has Tinder Gold, which means that for about the price of a Netflix subscription, he has optimized his chances for love. You, meanwhile, selected him based on a slideshow of photos and a few quips, which you chose from a wide array of other peoples’ profiles the same way you might choose one brand of yogurt over another, standing at the supermarket refrigerated dairy aisle.

The net effect of these technological forms has been to nudge us into seeing one another as the machines see us: fungible, expendable parcels of data open to classification and judgment.

But a nudge won’t push you all the way over the edge. Looking at his face across the table, it occurs to you that he really doesn’t photograph that well, or else looks handsomer in person. Or maybe he just doesn’t know how to choose good photos, doesn’t have a friend to help him out with his profile. And neither did you. For a second, you feel that sense of camaraderie that can emerge even on a bad date: two people lost in the same maze but searching for separate exits, nodding at one another’s trouble as you pass along into your own mysteries. Mismatched but not in an upsetting way. Just the facts of it. You could be friends.

One thing he asks, two mornings later after you say no to a second date, is what it was that made you swipe in the first place. You honestly aren’t sure why you did, or what to say now. You close the app, knowing you don’t have read receipts on and therefore no accountability, and get back to it during your lunch break. Maybe you swiped because he seemed to look harmless. You aren’t sure. You say it was his answer to the question “mountains or beach?” He wrote “hills.”

“Okay, thank you.” he replies. And the connection ends there. With a sideways swipe, his face and name evaporate from the screen, no trace left.

And on the Sankey diagram about the efficacy of dating apps which he is maintaining to eventually post on Reddit, you become a fractional centimeter in a narrower arm of swipes that resulted in a first date but not a second. Maybe someday, he and the others who gaze on that diagram will find the one pin-thin arm that points to happiness, the needle pulled through a haystack of small talk. He has, at least, received Reddit gold for his Sankey diagram post.

And now, on a TikTok post by the government of Romania promoting tourism, soundtracked by Gracie Abrams’ “That’s So True,” you see far hills, girded by a pale blue sky. It’s neither the mountains nor the beach, and you think of his profile: hills. And you think of his laugh, a little tentative in a cute way, as if he meant to test it by the gauge of your eyes and see if he should push it further.

Maybe you should buy tickets and go to Romania. There is a link to the tourism website in the post. That would be a worthy thing to buy.

At certain moments, when overwhelmed by a question and having no real person to ask about it, you enter the query into Google and read what people on Quora or Reddit have to say. Or what the AI overview now, floating above the search results, has to say. Or, clicking one of the link buttons off the AI overview, what a Psychology Today article in crisp SEO-optimized paragraphs, has to say. The article’s sentences fold neatly like the corners of clean linen on a bed. The hotline number, for if you need help, wavers in italics at the bottom, right above the little icons to share to Facebook, Instagram, and the outdated orange “B” of Blogger.

There is no answer there for if you will ever not be alone, and so you shut the phone’s electric eye and slip it into your pocket, reclining against the stiff seat of the subway car. You stare out the window watching the opaque whoosh of the tunnel go by. In the dark glass, you catch the thinnest reflection of yourself. Having run this far while carrying those dearest and heaviest to you at your hip, in your pocket, there is no option but to turn back around to where you started, answerless at the edge of a canyon full of nothing but empty air and a far way to fall.

And yet, when the war, or the police state, or the hurricane, or the AI murder-bot comes knocking at the door, we will miss these days of looking at the screen and failing to find what we were searching for.

Another banger! Your ability to weave incredible substack sources and intriguing narrative in with foundational media studies theories is refreshing every time I read!

Great read, as usual!it's useful to consider how the phone "sees" us, and a good reminder that the more time we spend with it, the more we may unconsciously adopt its limited and limiting perspective.